Interview by Leoni Fischer

Everything in the world bears witness to its own production. The works of the German artist Maximilian Prüfer, however, can be read as explicit reflections on the conditions of their creation, as multi-species collaborations in time and space. In that sense, the traces we see on his Naturantypie’s on paper point to a performative element that foregoes the presentation of the finished work. Instead of a panting ground, the paper here must be understood more as an arena or stage. In Forming Thoughts, a recent series of works, Prüfer worked with tiny ants whose traces are almost invisible. The collective trace only emerges as lines in repetition, in the process of an ant trail. These trails unfold as connections between different food sources that Prüfer lays out for his non-human collaborators.

But once the viewer gets to see the work, the show is already over. Confronted with abstract white marks before a dark ground, which could also be associated with a microscopic image of cells or tissue, the viewer’s imagination is not only challenged to reconstruct a lived experience that isn’t their own. In the process, the artist began to wonder if ants think as a collective, perhaps outside of their body. Speculating even further, this could be compared to the functional principles of our brain.

And in fact, while looking at Prüfer’s work, one too has to let one’s imagination take a leap beyond the boundaries of the human body, instead thinking of oneself as a living being that consists of thousands of living beings. For Prüfer, this was one of the main challenges in making the work. Similarly, the finished piece demands much concentration from the viewer as one’s mind wanders along the trails and further into the collective emotion of ants. As a reward, the contemplative power of the work unfolds just as one allows the thoughts to get lost on this non-human footpath.

What came first, the chicken or the egg? Re-tracing the ants’ trails, one quickly arrives at this old philosophical dilemma. Following the Spanish poet Antonio Machado, there is no path, the path is made by walking [1]. In the context of Prüfer’s work, this holds true on multiple levels. On the technical side, the most basic level at the same time can be considered the most difficult. The path of the ants emerges through them walking across the Naturantypie, which Prüfer describes as “a very fine coating on paper, which can be displaced by movement“.

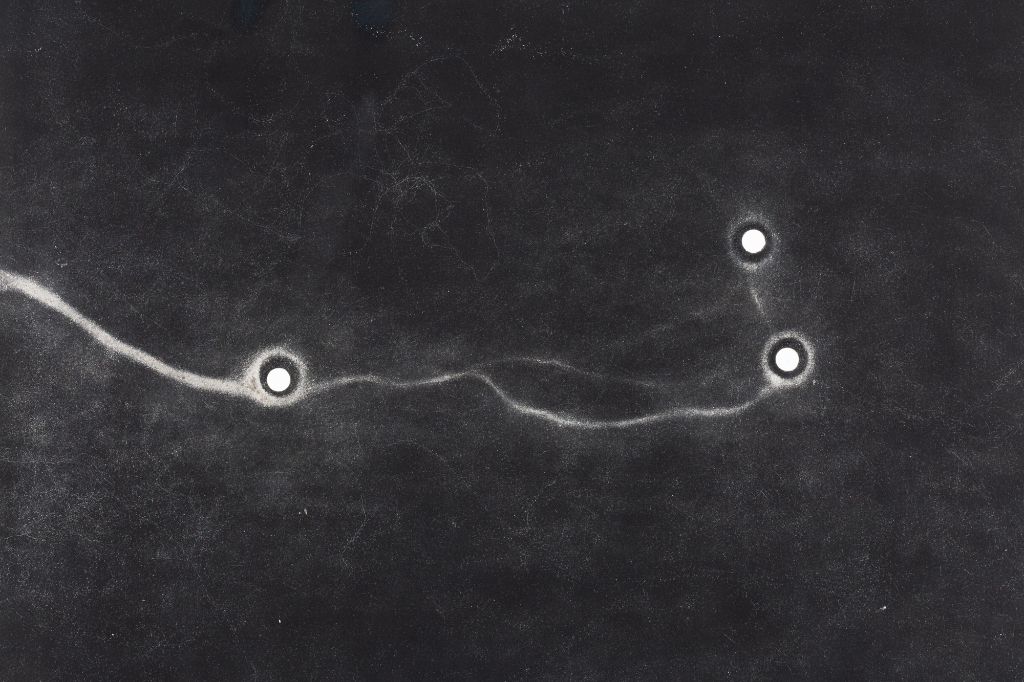

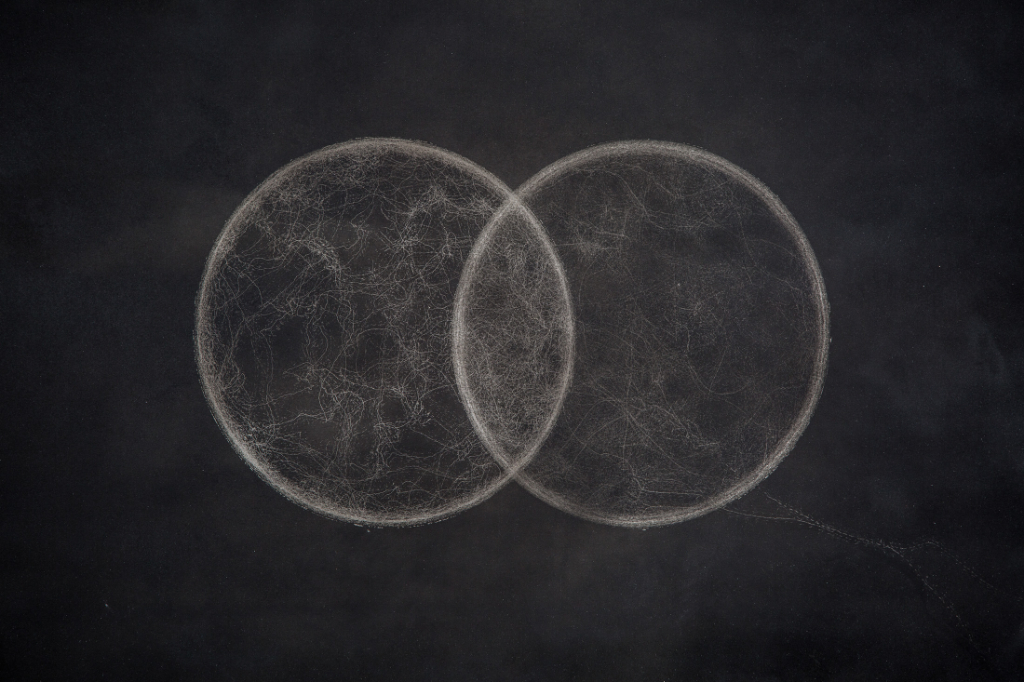

Along its way, the sum of animal movement gets condensed into a pattern of intertwined lines. Yet what prevails as one looks at the work is the impression of unidentifiable marks until our eyes start to move along the lines and shapes. As the mind follows the eye, we ultimately realise the marks as paths. In the case of Two Ants (2015), uncountable fine trails cross through each other.

Like parts of a net, they all seem to touch on an invisible boundary. This border emerges from the background as a more dense, defined line forming a perfect circle. Two of these circular arenas geometrically intersect to lay out a separate space within the overlapping segments. In there, the paths of two ants seem to meet, sparking speculation about whether or not the two individuals were ever there at the same time or if one had left its’ marks after the other was already gone.

Just as the ants’ movements seem to have been constrained by some circular outline, the viewers’ mind gets caught on the cyclic path, going around and around in an endless loop. This repetition could be seen as a state of comfort, as it becomes a familiar path, a known walk. Yet, given that we are used to instant, varying stimuli, fast answers and multitasking, repeating the same circle round after round is, contrary to intuition, a state of discomfort because we are uncomfortable with boredom. In this world full of fast-paced information and infinite image scrolls, we find ourselves used to being afraid of missing out on something better, shareable, and Instagrammable.

The strong meditative character of his works might derive from Prüfer’s background in calligraphy. The art of calligraphy is cherished wherever the copying of sacred texts was historically classified as a sacred process itself. This practice values mindful repetition instead of singular acts of genius. Many calligraphers, therefore, point out the meditative character of this art form:

The tranquillity of this work fills the whole being with an all-embracing contentment, where time and space, for a short time as if wiped away, no longer concern nor trouble us [2]. In this sense, by re-tracing the ants’ paths with our eyes and minds, the work invites us to set our inner clock to the time of a different species – which unlike ours, doesn’t obey the human-made rhythm of rushing minutes, hours, days, weeks and years.

Some of your works spark associations of cyanotypes made in the context of the natural sciences – for example, the documentation of plants by botanist Anna Atkins from the 1840s. When did you start working with other species, and what sparked your interest in the natural world?

As a child, I have already done various experiments and invented several things in my youth—for example, environmentally friendly fireworks or solar roof tile. I have always been interested in the interweaving of different disciplines. During my studies in design/calligraphy, I became increasingly interested in traces of animals, from which one can gather information similar to writing. Through the development of Naturantypie for over 12 years, I have discovered more and more of these traces that weren’t revealed before. It is like a door to another world. Suddenly, the trace of an aphid or an ant becomes visible. Something so small suddenly becomes comprehensible. It becomes perceivable how the animal behaves and how it reacts to certain situations. Already relatively at the beginning of my work with the animals, I noticed how similar we are in our behaviour. Which basic behaviours connect us. These philosophical insights connected to my fascination for nature, technology, and aesthetics. As a young person, I was confronted very intensely with death. At the same time, I was brought up very atheistically. Grasping nature was a way for me to grasp death. This took away my fear and made me perceive life as something completely wonderful.

Naturantypie is a special technique that you developed for your work. How did you come up with it, and what distinguishes it from conventional methods like Monotype?

You can imagine Naturantypie as a very fine coating on paper, which can be displaced by movement. The paper colour becomes visible where the layer is microscopically displaced. With this technique, it is possible to show even the most delicate traces of nature.

This is an extremely simplified explanation. The technique is so complex regarding the paper, layer thicknesses, and fixation that even after 12 years of development, I still feel I am at the beginning. Each image needs a combination of all factors to depict what is happening. A raindrop differs from a fly, so I have to explore many tests for each work.

Many of your works can be read as behavioural studies of various animal species. Which ethical implications come with this way of working?

Since the cyanotype is a photographic process and usually has a fairly long exposure time, I do not believe such trace images exist. Natural cyanotype works with pigments and can record traces even over periods of years. This would not be possible with light-sensitive materials. All work components are natural substances and do not harm the animals. That is extremely important to me. Especially the access to their behaviour has made me very mindful, and many animals that are otherwise considered pests in the general population, such as snails, ants, woodlice, etc., have become even more beautiful and worth protecting for me. I have also done very different political work on the mortality of insects in China to make Europeans aware of the mortality of insects in Europe.

How do you describe the interaction between you as the artist and the animal as the performing agent? To what extent do you influence the movement of the animals during the process? What is predetermined, and what remains open? Which hierarchies remain between man and animal, which are dissolved?

This isn’t easy to describe. It’s a constant change. Mainly I observe something coincidentally; for example, two years ago, the beginning of an ant trail on a leaf. Then I do different experiments and try to discover the quintessence. In the process, I often encounter amazing things and learn a lot from the creatures I work with. For example, while working on the pictures with ant streets, I began to wonder whether the ants think as a collective, perhaps outside of their body, similar to the principles of functions of our brains. Through compression, neurotransmitters and the principle of repetition determine structures. The images, therefore, appear as an image of a nervous system or synapses.

The animals usually give an impulse, and I try to understand them as well and openly as possible. In this process of becoming closer, the images then emerge. In the Forming Thoughts works, for example, I laid food sources on the pictures in the same proportions as my body scheme. The viewer looks at both: The ants and me. Because I am larger than the animals, I try to replace my predominance with responsibility. The work aims to dissolve the separation between man and animal.

I try to understand myself and all living things as realities that first transform the cosmos from nothing into an existence in which we perceive it together in different ways. If there were no life in the universe, it would not be. For me, life is the possibility created by the cosmos to become real. As if the universe had created itself twice.

According to which criteria do you select your “models”? What role do references to their cultural-historical connotations or iconographic meanings play?

I mostly follow the observations from the pictures taken before. Then one leads to the other.

You have worked with ants for a long time in your most recent series. Can you tell us a bit about your challenges in the process? Did you make any unexpected observations?

Last few years, I worked with large forest ants whose tracks were easier to capture in the image. They were tiny ants; the depicted tracks seemed like clouds over days and finally turned into an ant street, like a trace of a collective being. To think oneself into a living being that consists of thousands of living beings was challenging. Precisely because a swarm of ants does not behave as science often claims. And an ant trail does not lead linearly from burrow to forage.

Yet, together the ants almost have a kind of emotion. At the same time, I took drone photos of trampled paths of humans. These are visually so similar to the ant trails that I am sure we also form a collective creature without being aware of it.

Many streams of contemporary theory like Ecofeminism, New Materialism or Posthumanism seek to dissolve a dualistic understanding of human and nature as separate spheres and promote the formation of multispecies alliances. In which ways do such approaches inspire your work?

Honestly, I deal very little too hard with these theories because I generally find them very difficult to read. Therefore, I can, unfortunately, say little about it. For me, merging nature and culture is essential to conserving wildlife. Something will change significantly when we understand that we are primarily destroying ourselves, not our environment. We need to recognise that every form of “culture” and “invention” is an extension of evolutionary processes that continue on a spiritual and collective level. Understanding this could lead us to acknowledge the condition for preserving that “invention”. Adapting to the ecosystem is the base of our relationships with other living beings.

A bird’s nest and a shell are built on similar principles. Both also have a similar function: preserving and keeping something together. Whether these are eggs, which should be warmed and protected from falling or whether it’s food that should not run out. We call one nature and the other culture. To me, both objects are ways of preserving life. Ideally, our products would be just as reintegrated into the ecosystem as a bird’s nest. I believe that the relatively young species of humankind still has to learn a lot, especially an understanding of “we”. And what nature is in essence: life that sustains and creates each other. In the context of an almost empty universe, these thoughts fascinate me and give me meaning and tasks for my existence.

Solitude or loneliness, how do you spend your time alone?

Unfortunately, too much of both.

One for the road…What are you unafraid of?

The end.