Interview by Miranda Remington

After traversing some quiet pockets of nocturnal inner Tokyo, I arrive at an unassuming location designated by MIRA新伝統 (‘MIRA Shindento’). Below some stairs, I am led to a bioluminescent hidden two-story space, swirling and pummelling to trance music, with an unconventional layout resembling a church or a gothic mansion’s foyer – through a former sushi restaurant – hosting in its expanse an underground realm of Tokyo’s nocturnal people. I’m far away from above-ground common sense, and my thoughts begin to untangle as I prepare myself for what is to come.

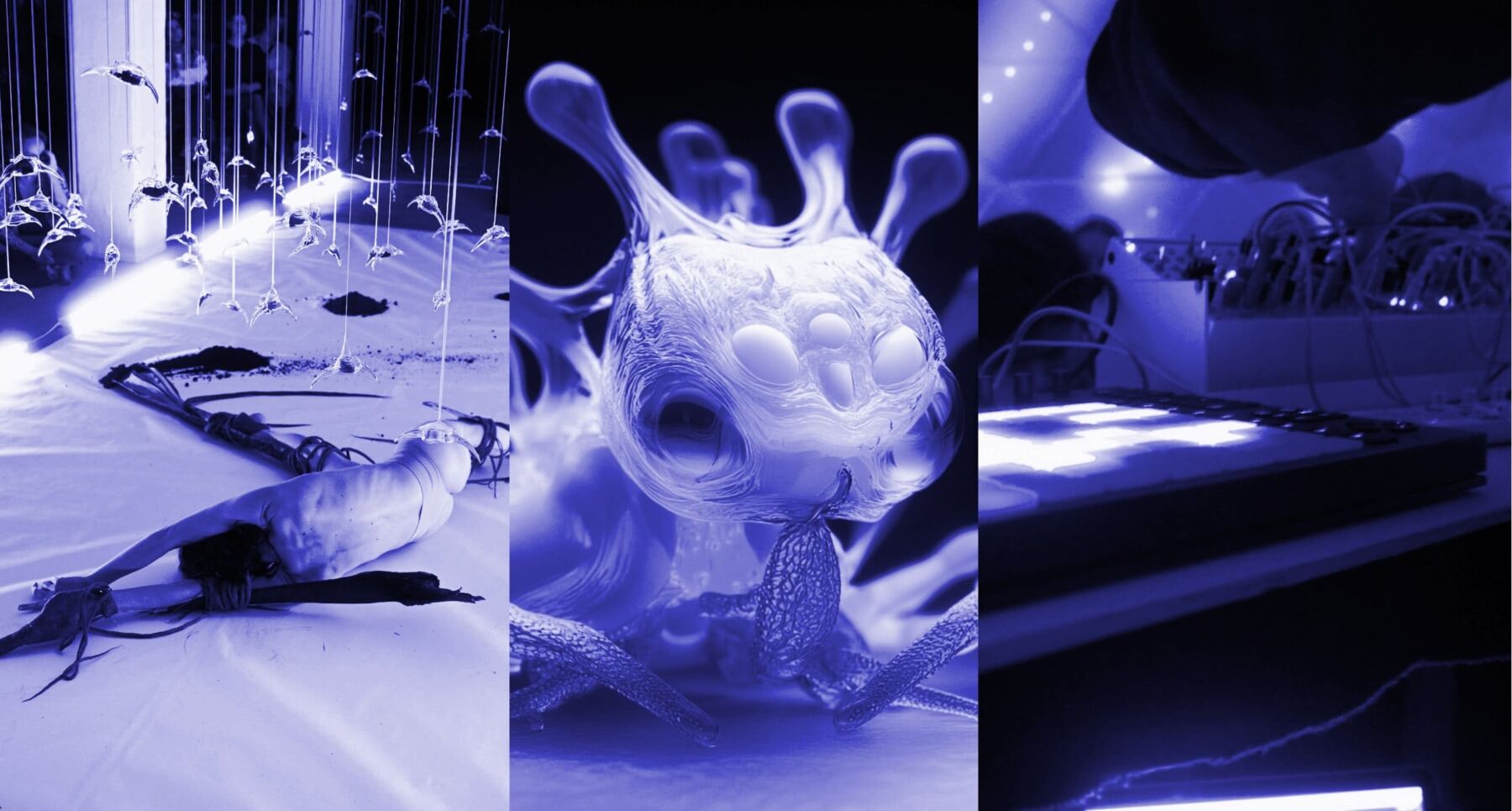

Comprised of the duo of Honami Higuchi and Raphael Leray, MIRA 新伝統 is an unlikely project to witness in Tokyo’s standard club settings, even though its sounds and visuals resonate with its dystopian surroundings. Their ongoing practice assembles electronic music, science fiction, digital media, performance, and several artistic disciplines into a unique post-apocalyptic vision. “Shindento” means new tradition.

Their project exudes post-human themes and spiritual airs in physical and virtual spaces. Alongside 3D rendered landscapes and other software-based hallucinations, the alien-gothic sounds of Raphael Leray summons unfamiliar entities and places outlandish, though seemingly still dimensionally linked to our neon alleys. The two spontaneously intervene in hidden spots across Tokyo’s underground scene, with the contortionist choreography of performance artist Honami Higuchi leading as pur-of-the-moment ritual theatre. As Leray’s operatic digital sound designs unfold from club speakers, Higuchi wields unique artefacts – weapons, metallic plates, accessories and other hand-crafted mystical items – to physically summon the unknown.

Here, a fanfare of swirling synths halts the standard mechanics of the night. The crowd parts to reveal Honami standing in the building’s atrium, holding in one hand a light source casting stark shadows across the room and a wooden cane in the other. A large metal plate is suspended from high ceilings, glinting mysterious symbols. Leary begins to churn rich synth layers from behind the decks, his esoteric compositions setting the scene for uncharted exploration.

Evolving his FM-synthesised textures, the resounding tonalities resemble artificial life forms which expand as they breathe. Honami Higuchi paces as she crawls and contorts, shamanically wielding her artefacts around the electro-acoustic swirls. Twisting towards the metal plate, she swings at it with her cane to let out rusted clangs. Once the seance comes to an end, there is a sense of acknowledgement amongst baffled onlookers that a form of catharsis has taken place. Entranced by unexpected extra-terrestrial opera delivered like guerrilla-style Dionysian theatre, a chorus of whispers speculate on what was witnessed.

MIRA 新伝統ʻs anarchic presence has thus far been more prevalent in Tokyo’s club circles rather than in galleries and art institutions. Their experimental fiction reverberates through the enthusiasm of its underground communities. In the years leading up to their recent relocation to Athens, they have particularly been involved with local queer raves where their world-building intentions felt incredibly potent. Tokyo’s countercultural activity tends to bubble in sporadic pockets of freedom beneath a chaotic urban sprawl, consisting of individuals often extremely frustrated by Japan’s intolerant status quo. Beyond simply indulging audiences with cutting-edge expressions, MIRA 新伝統 outlandish visions are sites of freedom.

Their unique cosmic narratives ultimately blend subversive theories of the present – alongside science-fiction literature, the writings of Deleuze and Guattari, of Mark Fischer and the early CCRU collective – into the ancient potentials of ritual and storytelling. The project’s approach follows the mindset of science-fiction writers and philosophers like Ursula K Le Guin or Reza Negrastani, who use otherworldly narratives to speculate on alternative configurations of our world.

While honing these creative potentials, Leray and Higuchi draw from their histories of immersion into shamanic cultures, meditative rituals and esoteric texts. Their progressive uses of musical software and appropriations of virtual technology suggest how we can liberate our dispossessed bodies from materialist rhythms and consumerist daily life, while their ancient methods help us to see how we may still inhabit our strange surroundings.

Our distorted relationship to nature in modernity is brought to light. Delivered through a spiritual lens, these themes are especially compelling in the context of Japan’s animist pagan histories repressed under its late capitalist decay. A sense of enchantment is carried throughout the rest of the night as the venue’s neon pulse swings back into full-speed club momentum. At this crucial moment, I approach the two, enquiring about their personal stories as they continue their alluring craft of the unknown.

At SLICK, I witnessed an ancient ritual spontaneously takes place during club night. I wanted to ask again about your use of different objects in your performances and again about the importance of the metallic plate. I understand the symbol refers to the mice experiment Universe 25…

Raphael Leray and Honami Higuchi: Yes, it is derived from the conclusions of John B. Calhoun’s Utopia mouse experiment. Engraved on this metallic plate is a diagram by John B. Calhoun, illustrating the tensions and causal relationships between needs, conditions, and adaptations in social structures that he deduced from his mouse utopia experiment, “Universe 25,” which descended into chaos and extinction.

Mice were placed in a sort of perfect automated-communism utopia, with unlimited food and ample space for each mouse to evolve. The second generation of mice started to exhibit behaviours such as building micro dictatorships, committing genocide, rape, gratuitous violence and cannibalism, and the third generation, comprised of the survivors’ offspring, refused to reproduce and instead spent their days isolated from each other’s, grooming themselves, and waiting for death. Universe 25 is often used as a reactionary argument against collectivist and egalitarian approaches, promoting utilitarian and Darwinist capitalist ideologies, which, in our opinion, completely miss the point.

From our perspective, it is not the abundance and direct access to resources that eradicated the mice society, but rather the artificially forced isolation from our ecosystem and its diversity, the lack of symbiotic relationship with an outside. If anything, it is a warning about this insane idea of human society that could survive all by itself, removed from the constraints of compromising with the rest of nature.

We always strive for a multi-layered approach. At first glance, it is music and movements; upon closer inspection, it quickly reveals itself as a ritual. Behind the rituals lies a web of narratives and symbolism. There is no correct or incorrect interpretation of these symbols; they can have their own history as objects but are present in the rituals for what can’t be articulated in words.

Your use of technology allows your reality to extend into the virtual. Could you please tell me more about the digital tools you’ve been interested in lately? Given that these tools are evolving quickly in an uncanny way, how do you grasp them?

In the past, we both dedicated time to developing a solid understanding of underlying theories and focused on modular tools like Max/MSP or Blender, which don’t restrict users to specific genres and are regularly updated with the latest technologies. We tend not to go for tools with a robust representational mode (like the n-th TB-303 emulation or any genre-oriented synthesiser) and love to proceed from basic building blocks rather than hijacking existing ones. We are a cyber-era version of the Ferdinand Cheval.

Visually, we experimented with early versions of GANs, finding their glitches more intriguing than the hyperrealism currently popular on social media with mainstream apps. Production-wise, we now use them sparingly, blending our data, previous artworks, or photographs to create some sort of outsourced acid trips and dreams we could reflect on or get inspired from.

Setting aside the obvious economic challenges, we believe AI can be fascinating when used to enhance existing “noodiversity” and expand it, challenging normativity and anthropocentrism. However, this is only meaningful when the AI embodies the artist’s narrative and intention rather than merely producing endless eye candy. It becomes less compelling if it’s simply an efficient tool for plagiarising and remixing existing art.

Could you tell me again about how you two met? How did you naturally come to work together in this fluid, multidisciplinary way?

We met around 2017. Raphael was unsatisfied with the lack of interesting theatricality in the local experimental electronic music scene at the time, and Honami had just quit her job as a lead dancer in a famous Tokyo Cabaret Club and was looking to focus on her personal art projects and choreography.

We were introduced by a common friend and quickly started working together. It didn’t work out overnight, of course. It took a lot of time to discover each other’s strengths and weaknesses, and we tried various ways of collaborating before finding the right balance. Just to give you an idea: there were some pre-MIRA 新伝統versions where Raphael’s soundtrack was played back while he performed physically on stage with Honami , and others where we both sat through the whole show, playing music with interactive screen panel installations we built specifically for the performance. So, we both explored each other’s domains before finding the right balance.

What are your relationships with nature? Honami mentioned that the ocean is critical to her.

We are both against the reduction of so-called nature to a mere resource or mind lifting panorama but don’t have a personal relation to nature, or rather we don’t really consider that there is a dichotomy to be done between the natural and human worlds, this is the first mistake of anthropocentrism. Honami likes the ocean because of how humble it forces you to be. The ocean is one force on the planet that humans can’t really control or compromise with, and it is the cradle of biological life.

What brought you to Athens? How do things feel different to Japan from the perspective of being an artist?

There are myriad factors that attracted us to Athens. From a politically engaged artistic standpoint, the city is particularly captivating, serving as the cradle of Democracy and Tragedy, boasting one of the richest mythologies in the world, it’s also a country which has been victimized since 2008 by capitalist crisis and now the challenges of global warming like no others in Europe. We were also attracted by the activities of galleries like Hyperlink (https://www.instagram.com/hyperlink_athens/) and the artist community that gravitates around it, often working around themes of post-anthropocene, neomythologies, and symbiosis like no other.

In Japan, people have been depoliticized since the 70s, with existential and political anxiety about the future mostly redirected into techno- accelerationist delusions. The night isn’t used to conspire against the present or imagine a future; instead, it’s often used to forget tomorrow after being intensely overworked by their companies. Don’t get us wrong, there are wonderful people doing their best to push back against this tendency, but we are just too few, and sometimes stepping aside and growing outside of it is more efficient.

From a more aesthetic point of view, Millennia-old ruins in Athens coexist with the recent ruins of late capitalism, turned into anarchist squats and semi-autonomous districts, creating a unique juxtaposition. Athens is an extremely inspiring place to cultivate post-capitalist poetics and post-Anthropocene mythmaking.

How may your previous years together in Japan reflected in your output?

Musically, the early Japanese noise scene, the butoh scene, multidisciplinary collectives like “Dumb Type,” or animation works like “Angel’s Egg” by Mamoru Oshii, authors like Ryū Murakami, and filmmakers like Shūji Terayama have always been huge influences on us. To be honest, we’ve always been quite allergic to the “cute & positive” stuff.

The gap between those radical aesthetics and our daily life in Tokyo helped us focus on developing our own very personal world and radicalized us to some extent. It may vary significantly depending on your social class, cultural background, or the city you live in Japan, but Tokyo isn’t an easy city to live in for those who are not willing to conform to the escapist tropes of hyper consumerism and the blind, toxic positive thinking of the workplace.

Having a “Sense of Tragedy” is not well tolerated. This pushed us to distance ourselves from the techno-capitalist fantasy while attempting to embrace a unique situationist approach through rituals and catharsis in our shows. Our approach seeks to avoid any outburst of pathos or rage that could easily catalyse into yet another form of escapism or easy entertainment, while still leaving a mark on the audience.

Your work departs from reality, but I’m curious about how your backgrounds may have influenced it.

In her career, Honami has experience as a lead show dancer, where she managed stage setup, chose dramaturgy, decorations, and stage effects for new acts monthly. Later, she worked as a 3D designer for an architecture company, giving her a keen sense of space utilisation.

Raphael, on the other hand, is a software engineer by trade but also organised noise events and hosted an experimental bi-monthly radio show in the early 2000s on a French left-anarchist FM radio. He has always been passionate about philosophy and mythology, so the blending of technology and speculative fiction resonates with his background.

Given the ritualistic nature of your work, it’s also tempting to see a link, and I’m curious whether there were any inspirations in this sense.

We both have somewhat spiritual and ritualistic backgrounds. Honami was very interested in Taoism and meditation. She always felt a deep connection between dance and spirituality and was interested in shamanic cultures. On several occasions she created her own dances of mourning for the departed. She studied butoh under the influence of Tatsumi Hijikata, Sankai Juku, and Kaoru Kagaya. She was also greatly influenced by the works of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, especially their depiction of the human body.

Meanwhile, pursuing an engineering career and attending noise gigs, Raphael was initiated into a progressive French Masonic lodge in Tokyo (Co-Masonic Order of “Le Droit Humain”) in his mid-twenties before leaving to explore Theravada and Zen Buddhism. He has developed a strong interest in rituals and their operational modes within those communities.

These traditions are particularly fascinating because rituals are central to their message, while the belief system is somewhat secondary; faith is not the primary focus, and participants may not necessarily completely believe in it. They come to experience the social synergy of the ritual, which some would call ‘Egregore.’

The vague notion that rituals are necessarily old or associated with right-wing ideologies or belief systems is something we felt needed to be deconstructed and used as a situationist tool against the commodification of all forms of art. The ‘新伝統’ (Shin Dentō) part of MIRA新伝統 actually stands for ‘new traditions/rituals.

People in Japan have a unique relationship with technology and nature. Could that have been reflected in your output?

Japan has a unique relationship with nature, characterized by both reverence and apprehension. Sacred trees and animist beliefs coexist with hyper-protective tech culture, reflecting the country’s dense forests and vulnerability to natural disasters like earthquakes and tsunamis.

From this complex dynamic arises a dichotomy between techno-solutionism and the beauty yet hostility of nature. We reject this binary view, seeing human infrastructure and natural systems as part of a continuous, interconnected network of co- production. The belief in technological isolation from this network, as seen in the Universe 25 experiment, is flawed and risks catastrophic entropy.

Our work challenges the separation of technology and nature, drawing parallels with early animism’s view of interconnected.

Your work focuses on building new fiction. Have those themes developed in any way recently?

Yes, we’ve been immersed in crafting new songs and fiction for our upcoming album, exploring themes rooted in ancient Greek pastoral mythologies from a post-human perspective, Commedia dell’arte, cyber thievery, and clowns, we also got inspired from the recent works of this occult group italians thinkers named the Gruppo Di Nun .

However, we prefer not to reveal too much at this moment. What we can share is that while Noumenal Eggs delved into addressing capitalism as a demonic hyperstition from the outside, dispossessing individuals from their bodies, our current project revolves around proposing novel ways of being and becoming-other in a troubled world.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Financial precarity is the number one chief enemy of creativity, the discourse romanticizing financial precarity (which is tightly linked with emotional and mental precarity) and explaining that it is never an obstacle is bullshit.

When you truly don’t know how you are gonna pay the bills for the next months, and that no friends or family can support you, you are forced into prioritizing stable sources of income that leave little to no time for your artistry.

We both come from precarious middle-class and working-class families, our twenties were all about self-learning and finding stable jobs with no further education than highschool. This is only entering our thirties that we could finally dare investing more time in our artistic practice.

There are always exceptions that are used to justify and normalize precarity but there is no doubt that the current economy has nipped in the bud many potentially great artists that will never develop their talent and that there is an insanely disproportionate representation of the bourgeoisie.

What could you not live without?

It’s gonna sound corny as fuck, but we could not live without each other. Materialy speaking as long as we got a roof, food, and enough time to create it is fine.