Interview by Christopher Michael

Reading Italo Calvino’s essay Cybernetics or Ghosts is an eerily prescient experience. In the essay, Calvino boldly asserts that, in the near future, a machine would be able to take the place of the writer. Specifically, Calvino believes that a “poetic-electronic machine” might soon create poetry as good as a human. While Calvino’s ideas may have felt far-fetched in the late sixties, today, thanks to the advent of generative AI, they feel all too real.

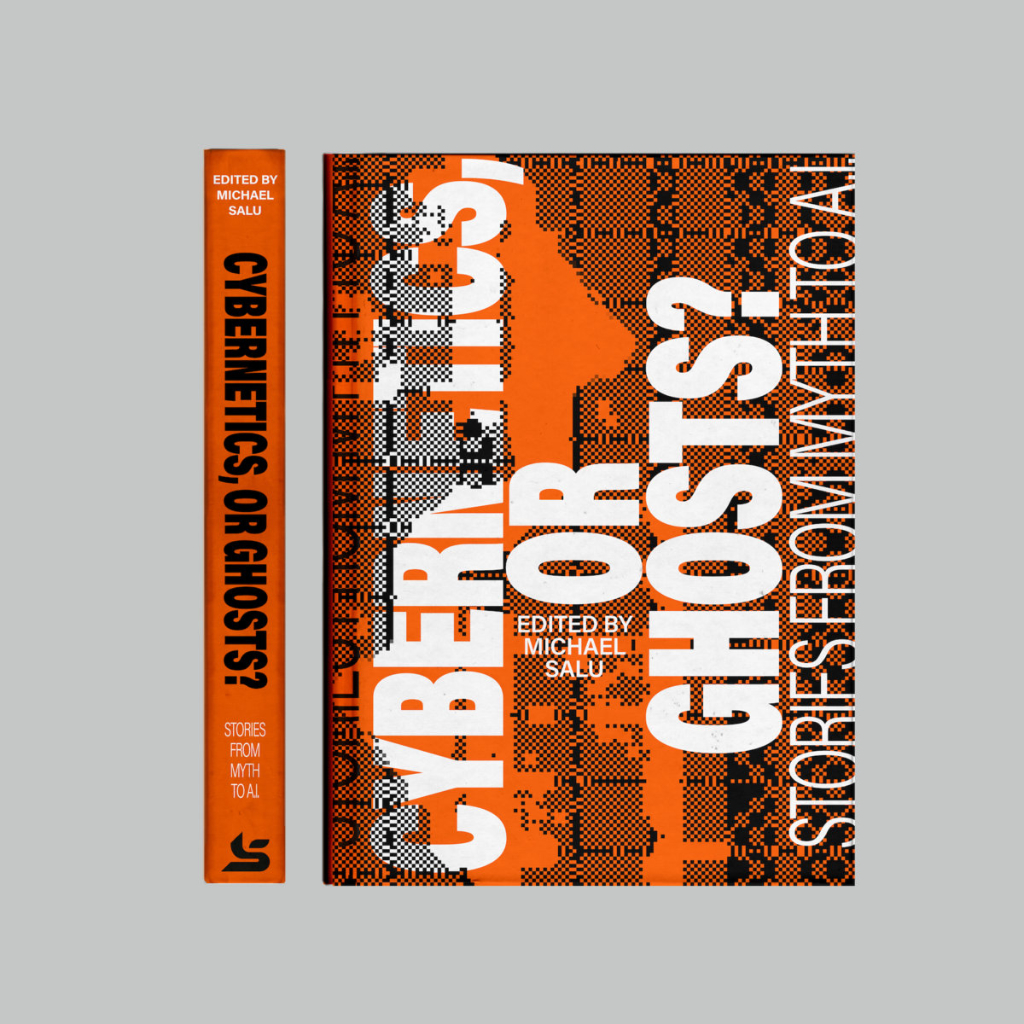

Subtext Recordings’ latest literary anthology, Cybernetics, or Ghosts? — Stories from Myth to A.I, takes Calvino’s essay as its starting point, inviting writers from across the globe to respond to Calvino’s prediction in the contemporary moment. The anthology’s editor, interdisciplinary artist, writer, filmmaker, editor, and creative strategist, Michael Salu, felt that it was critical to reconsider Calvino’s work within the current discourse. Considering the rise of generative AI and large-scale language models, Salu was interested in Calvino’s ability to [alert] us to why language, literature, and storytelling are essential to our species.

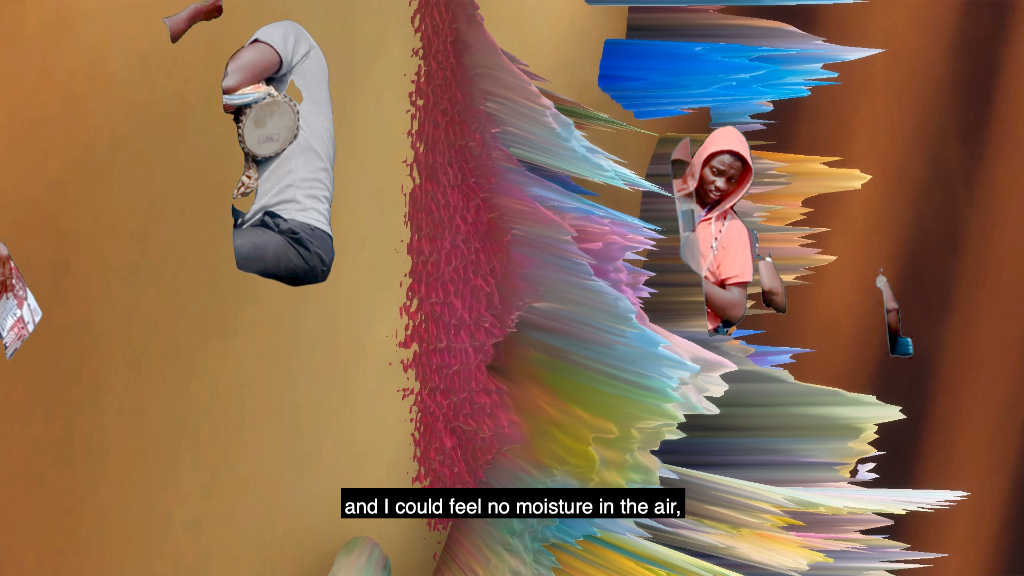

Salu’s diverse creative background, often working simultaneously across multiple disciplines, lends a unique vantage point to the project. Salu is the type of artist who finds equal enjoyment in reading classic literature and learning coding languages like Python. His artistic output has ranged from conventional filmmaking to designing book covers for classic literature to creating virtual worlds using game engines. His work Solitary Breath is particularly illustrative of this.

The idea was born from The Red Earth Project, an artistic research project asking how alternative cosmologies can be better represented within virtual architectures powered by AI innovation. The film blends prose, deep learning models, video, and 3D software to consider cross-cultural realities in virtual space, particularly inspired by Yoruba mythology. In this way, his artistic and academic practice is representative of the changing boundaries of creative work, ultimately advocating for new approaches to artistic production.

The Cybernetic or Ghosts anthology also exemplifies these new ways of thinking and features a sister compilation of music inspired by Calvino’s essay. Moving between sonic and literary experiences, those who read or listen to the compilations can explore new dimensions within the work. Salu describes this as a polyphonic conversation started by the stories but has now become an entire orchestra of ideas. The musicians involved were asked to respond to the texts, reflecting on how generative AI technologies are changing music production methods. This expansive inquiry highlights new ways to approach creative work, embodying new modes of thinking not beholden to rigid disciplinary lines.

Italo Calvino seems to have impacted your creative career, from designing book covers [1] for some of his recent reissues to engaging with his work more theoretically. Could you tell us more about your relationship to Calvino’s work and his importance to you?

Wow! It’s cool that you found those covers. It feels like a long time ago. I used to do design and art direction in literary publishing. At the time, I was working for Randomhouse (now Penguin Random House) and serendipitously got hold of that series to redesign. As was often the case with Calvino’s creative writing, I set a constraint: I would develop a series of narrative visuals just from typography.

I first encountered Calvino’s work in my teens. I’ve had many literary points of reference over the years, but what caught and sustained my interest in Calvino is his seemingly boundless curiosity as a writer and thinker and how this fed his playful and exploratory output. He was a writer whose sense of wonder and imagination wasn’t dimmed by theoretical thinking but deftly drew the two realms together. I think this approach is also reflected in the way I work.

You recently edited the fiction anthology Cybernetics, or Ghosts? based on Calvino’s seminal 1967 essay ‘Cybernetics and Ghosts’. How did this project come about, and what inspired your involvement?

Over the past decade, I have been developing creative and critical work about our relationship with technology. I’ve used different forms to communicate these ideas, including books [2], short stories, essays, artworks, films, talks, and collaborative creative and research projects. I’m also interested in how both overt and covert applications of technologies influence the human condition, from a geopolitical level to the individual. I track how much we’re at the mercy of invasive tech, relying on various services and platforms, which then shapeshift, often leaving us scrambling and subtly changing social behaviours. I’m also interested in our relative lack of vocabulary for existence in the digital realm, particularly within the world of literature.

Literature can be used to explore ideas around tech. Yet, the poetics of language, beyond its technical dexterity, are increasingly relegated or distanced from the core innovations even though language itself is a key tool and methodology for computational development. I find this disconnect an interesting place to explore, so I’ve been keen to write creatively into this technological space through my own writing and collaboration with others.

This anthology began as a literary thought experiment for a guest edition [3] I put together, commissioned by the UK literary platform WritersMosaic. Gabriel Gbadamosi, an editor at WritersMosaic, was familiar with my work and invited me to put a feature together on writing and technology. At the time, I was revisiting Calvino’s anthology of essays called The Literature Machine, which includes his essay Cybernetics and Ghosts. Responding somewhat to datasets, I thought it would be poignant to look to the past to think about the future of writing, and it just so happened that Calvino’ had written the perfect essay on this subject.

I invited some brilliant writers and thinkers to read Calvino’s essay and respond with a short work of fiction or essay. I enjoy initiating these kinds of projects, as I’m already well-engaged with a contributor’s work, so the fun comes, knowing they’ll produce something interesting, but not knowing exactly what that will be, there’s calculated decision-making there, based on one’s knowledge, but also trust and chance.

Subtext and I had been discussing collaborating on a literary project for a while, and I realised the guest edition could expand to a complete anthology. For this printed volume, we focused only on fiction, as this offers an enduring enigmatic quality and room to let the poetic imagination flow far into the past or deep into an unknown future. Our stories encompass it all, speaking to myths, technological ‘life forms’, iterative body modification and much more, making a fun and intellectually stimulating volume.

A central question in Calvino’s original essay is about the machine replacing the poet. Calvino boldly asserts that an intelligent machine may eventually be able to compose poems and novels. As generative AI has improved in the last few years, we have seen this assertion become a reality. With that in mind, what do you see as the importance of Calvino’s essay within the current cultural climate?

When writing that essay back in 1967, Calvino was researching nascent developments in computational linguistics, which got him reflecting on future possibilities. I think Calvino’s essay does well in alerting us to why language, literature, and storytelling are essential to our species. Storytelling has always rendered experiences, time, life, death, love, grief, failures, and various emotions.

As language and storytelling have evolved, we build mythologies around nation-states and cultural histories. In a sense, Calvino poses the question of why this is important and what then changes or fails the human condition when this responsibility, or even its pleasure, is removed from us. For better or worse, generative AI becomes a method of collective storytelling (albeit incomplete) but is, as yet, removed from us, and who knows whether we’ll find a way of connecting cognitively or even metaphysically with this dynamic swarm.

Cybernetics, or Ghosts? features a sister compilation of music inspired by the texts. How do these two elements, the textual and the musical, complement each other in this project?

This collaboration has been so much fun to put together, and it’s exciting to present such a cross-disciplinary project (which should happen more often). Subtext has been a conduit for expansive progressive sound for such a long time that it felt right to create a dialogue with literature which does the same, differently. There’s something unifying in each artist’s conceptual origination and confidence, and they’re all interconnected, like a series of nodes, with Calvino’s essay nestled there at the centre.

I like to create works that stand alone but revere their links to other works. I think we also tapped into how musicians of the like working with Subtext might think or intuit anyway in how they pull various references into the creations. So we’re able to have a polyphonic conversation, started by the stories, but has now become an entire orchestra of ideas.

You have worn many hats within your creative career: creative director, photography editor, and researcher. How did editing this anthology compare to other artistic pursuits you’ve been involved with?

That’s an interesting question. These areas of my work might seem disparate from the outside, but there’s a continuous through-line. It’s always about ideas and finding different ways to express, visualise, or communicate them, creating an activity ecosystem, and doing so with others. As a photography editor, I’d seek work offering a distinct dimension to a core concept or grouping different works to say something new.

As a creative director working in the cultural sector, I’ve been responsible for ideas and bringing people together to help further that vision while feeling free to make it their own. I think you see this same approach in this anthology. From my core idea, each writer has been able to create their world, which is its own thing but links right back to the concept at the centre. There’s a resonance of the experimental literary group Oulipo in this work. I’ve worked with writers one way or another for many years, often as an editor, so the anthology was a natural progression.

In work like Diabolical Architectures of Colonialism or Solitary Breath, you use media technologies like game engines and 3D sculpting to criticise the capitalist/colonial regimes we live under. What draws you to using new media forms for such critiques?

With a creative studio [4], I’m always adding new methods to my toolkit, and I’ve been working in 3D for some years. I have ongoing and complicated reflections about agency. I have access to these tools and software, yet I’m acutely aware of the resources required to use them. I’m interested in current and future forms of archiving, like metadata, LIDAR, and what autonomous memory does to determine which version of the world we see and believe in.

I consider how to dismantle the hierarchical gaze of vernacular record and digital utopias. There’s something about the way we can manipulate time and space in 3D that I find interesting. With an engine simulating the temporalities of earth, from physics to biological life generation, are modes interesting to consider conceptually, with the potential for transgressive interventions—re-imagining the official conscious and unconscious temporalities of colonialism. It’s often a speculative thought, as to do what I have in mind would require building an entirely new codebase from the ground up. Much of the work I see created in new media spaces leans more towards utopian ideas of the future human, often leaving out large human and non-human world swathes.

One cannot consider resource extraction and climate decimation without outlining the connection to the ways we ‘other’ large swathes of the world to gain access to resources whilst decimating and making their environments inhospitable and upholding demonising narratives and stereotypes for economic purposes. I focus on redressing that balance a little, thinking about how the virtual space captures and erases a lot of cultural memory. The Red Earth Project [5], from which Solitary Breath comes, takes this thinking deeper, looking to the metaphysical origins of the statistical theorems informing today’s AI and reflecting on their intent.

How do you manage working between different forms of media in your practice? Or, in other words, what is your thought process when choosing which mediums to work in and when?

Years of academic and self-taught training give me confidence in moving between media forms. The way my career began, both working on design and art direction in publishing and as an independent artist, meant I needed to learn new methods constantly and learn quickly, whether that be how to direct a photoshoot or create a complicated illustration or animation. Over the years, my practical skills caught up with my ideas, and now it looks wild to the observer, but this approach and broad skillset formed over time. I enjoy learning and expanding my craft, whether figuring out how to use Unity or developing my knowledge of Python.

As for literature, this has long been a personal dimension, more so than an academic one. I’ve been a reader since I could read, and I’m a huge advocate for how having a reading practice can really aid in understanding a wild and complicated world. So, it’s a life-long personal scholarship that informs and, I think, strengthens my art practice and eventually led to me choosing to write as well.

In your opinion, what is the value of an interdisciplinary approach for artists working today?

I’d suggest the market economy has been possibly too influential in categorising creative thinking and making. You’re a 3D artist, you’re a UX designer, you’re a video game writer. There’s so much overlap in just those three professions I’ve mentioned, and yet we define them so strongly. I’m not against disciplines, but I think those definitions could be looser and for industry and academia to be a little more adventurous, as it’ll make for more impactful and long-lasting, transformative work beyond these silos and simply the monetary bottom line. Like Calvino, I think expansive, uninhibited, but informed creative thinking will endure, even as we get to grip with new ways of thinking and seeing.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Admin.

You couldn’t live without…

Books and water, in no particular order.