Interview by Eleni Maragkou

In uncertain times, punctuated by volatile temporalities as a result of digital mediation, the feeling of unrootedness can become overwhelming. Familiar anchors to history, land, and physical presence are destabilised by the ephemerality and opacity of digital and media infrastructures, fragmenting our sense of self and place. How does technology reshape landscapes, and in turn, how can landscapes ground and reshape technology? How do we build meaning in dirt and data?

By situating the digital within the material, Glasgow-based multidisciplinary artist Matthew Cosslett dismantles the abstract notion of the internet, making it a tangible, almost tactile entity, which he weaves into the topography of rural Scotland, where they grew up. An MFA graduate from the Glasgow School of Art and, more recently, Margaret Tait Resident with LUX Scotland, Cosslett uses landscapes as a canvas to explore how digital networks interact with personal and collective meaning and critically examine how technology reshapes our understanding of identity, landscape, and memory.

Drawing from ephemeral archives and personal geographies, Cosslett employs video, photography, text, and sound to highlight the nuanced interplay between digital and physical spaces—how they mirror, resist, and reshape one another. These places serve as sites where the network’s complex and often contradictory realities—such as its virtuality and materiality—are projected onto landscapes already rich with historical, emotional, or cultural significance.

Navigating the production and proliferation of visual content by meticulously gathering morsels of user-generated content from platforms like TikTok and YouTube, Cosslett dexterously blends archival research with speculative interrogations into the constructedness of landscape and data. However, Cosslett does not merely lean into investigative aesthetics, nor does he trust the camera as an inherent truth-teller. The land is not a neutral territory, just as data is never raw.

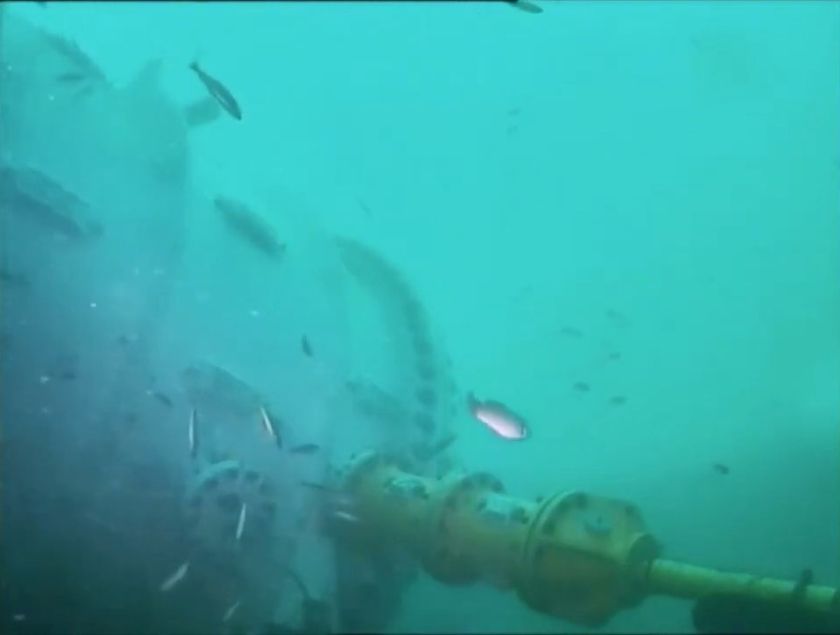

There are seductive connotations of purity inherent in the imaginaries around data and land(scape), which Cosslett is keen on disarming. Their moving image piece, ‘missing in-crypt tides’, locates and lays bare the entirety of the network—user, content, experience, and infrastructure. Oscillating between Orkney’s bustling cruise ship industry and the submerged Microsoft data centre off its coast, the piece draws parallels between tourism and technology, riffing off the opacity of encrypted data and illuminating how each reshapes and capitalises on physical space in its own way. At the heart of ‘missing in-crypt tides’, available on the CLOT website for a limited time, lies the coiling tension between the body and technology—the visceral unease that stems from the deeply human drive to inhabit the media one consumes.

Your work explores the intersection of Scottish and digital topography. You’ve also completed your MFA at the Glasgow School of Art. How does your connection to Ballantrae, South Ayrshire, and Glasgow inform your exploration of landscape and place?

Being from a small rural village, Ballantrae, and practising in the giving but contradictory city of Glasgow, my practice has always been rooted in the Scottish landscape. Scotland is a place of hybridity, with competing forces of tourism, industry, and belief layered on top of its land. I’ve found Scotland a useful place to access the whole—for example, I think the particular ideological and practical condition of the landscape here is analogous to a digital environment.

With work that challenges or encounters technological realities, place offers a grounding tension and a frame. Rooting and locating technology somewhere specific disarms the network, making it less nebulous by being able to point at its limbs—it’s here; it does this. A more linear example would be when you lose radio reception in your car, you can look to the hill you are driving past and understand that this physical topography is blocking your signal; the same is true in more nuanced ways for the network. I’m interested in the hill and the signal shaping each other, especially when you consider the hill a place holding its own meaning, associations, and projected desires.

Placing technology somewhere, often rural Scotland for me, also offers my work more expansive and naturalistic forms of knowledge production. Whether that is something from inside a place, in my work that often is the folk tradition, or whether it is the space for deep feeling, for sadness, for a road steeped in associations, for memory. Again, this ‘inside’ knowledge provides a reprieve to its technological counterpart, which exists but is always harder to hold because of the actively captured and capitalised relationship to meaning and feeling that exists on platform technology.

I think ‘missing in-crypt tides’ was the conclusion of this way of thinking for me. With ‘missing in-crypt tides’, I was thinking inside the ‘deep network’, and this process changed how I want to approach making. I no longer feel the desire to delineate between physical and digital space to the same extent, and I think this will allow my practice to flow naturally and intuitively between modes of thinking. I’m not sure where this will take me, but I am gaining a lot of joy and strength from working intuitively with material, thinking from inside the house rather than situating the building within its topography. I am turning more inwards, thinking maybe more about personal geographies, maps of internal sense-making and deep feeling.

You describe your process as ‘transmuting networks atop imagined places’. Can you elaborate on how you merge these imagined realities with physical landscapes in your work?

I mean, how do we talk about the ‘internet’? As a collection of infrastructures and social institutions that forms a space, the internet is increasingly and intentionally amorphous, hard to define, and hard to locate. Even on a content level, an imagination that we might have had of the internet as holding things —information, experience— is increasingly less accurate, with an onslaught of AI slop and the continued degradation of archives. We know that the internet is an infrastructural body —a collection of cables and computers— even if it no longer holds anything. For me, the process of transmutation in my work has been about combining these states and bringing the amorphicity of the network back into conversation with its structure.

I think the data centre of ‘missing in crypt tides’ represented a conclusion or a summation of this mode of practice for me. Data centres are built as abstract monolithic blocks located on the periphery. They are in the desert or the sea, attempting to elude geography and place, to be unlocatable, to become the black box (not disconnected from wider notions of the periphery or the frontier we see in the American Western).

This is to say that the data centre attempts to be an imagined place, supplanting physical geography with an imagination of the network as monolithic, amorphous, non-specific, impenetrable, magical, and unstoppable. ‘missing in-crypt tides’ is a resistance to this logic, an attempt to consider the deep meaning of a data centre’s geographical location, to consider what it means to sink all conceivable information under the sea. The data centre is a dense manifestation of imagined realities; it is a platonic object that sits tightly at the intersection of ideology, physicality, geography, and the network.

In previous work, I brought the network back to its geographical context, locating uploaded videos on a map. Still, the data centre’s intention and density already embody this process. For me, it was almost a readymade and a black hole, already combined, an image.

In your practice, you use ephemeral archives like YouTube. What draws you to such temporary or transient forms of media, and how do they inform your exploration of place and landscape?

YouTube used to have it all, but those days are over—or at least numbered for the platform. I love it. It’s easy to think of YouTube as the mass—a repository for everything you could imagine. But this misses YouTube’s magic and the deep search for meaning and connection that fuels the capital engines of technology.

YouTube, to me, is personal, intimate, and vulnerable, and that’s what I love about it. A lot has been thought, I think, about YouTube as a network, considering what it means for a video to be situated next to others– as a part of an interface, a linkage of recommendations– but I don’t really think that is the truth of YouTube if it ever was. I believe this is made clear by something like TikTok, where we see true multilayered interrelation. Instead, YouTube is solitary to me (and I do think much of its more surface-level content holds an intentionally pensive tone), full of small, accidental videos, often old, often personal, a semi-private archive, a window at night with the light on.

I think a clear relationship to the camera is performed with digitally ephemeral media. A YouTube video with 10 views is not hyper-produced, attempting to appear like the real— it’s shaky, broken, lost. I want to be careful about romanticising, but I find this honesty or unintentionality useful. The camera is biassed and fundamentally limited by and performed within our physical interaction with its objecthood. This relationship is performed in the resulting video as a sort of shadow or maybe even hauntological geography- you can understand a person’s shape and thoughts by thinking about how they are holding the camera, how long their arms are, what they are seeing versus what they are recording (I believe almost here about the logic of the info-sec Twitter account or the GeoGuessr TikTok, this back-working). I try to locate my work in that shadow, in the slip that demonstrates that a person is responsible informed by their location and thoughts, and I find YouTube a fertile place for this kind of information.

You work across multiple mediums, including video, photography, text, and sound, and your chosen themes and tools remind me of the work of Forensic Architecture. Are you familiar with their practice, and if so, how do you relate to it? How do you decide which medium best expresses your projects’ themes and meanings?

Yeah, that is really interesting and something I’ve considered. I have to admit that I’m innately suspicious of investigative aesthetics, like Forensic Architecture. I’ve built my practice on a suspicion of the camera and a deep doubt of the truths it tries to sell. I am trying to resolve this feeling.

In 2020, I created a work called ‘they could not be seen’, which used videos taken from a data leak of the alt-right social media platform Parler and geolocated them to a specific point on a map. In many ways, it attempted to both utilise techniques offered by investigative aesthetics and complicate them. It showed their blindspots when turned inwards, when not thinking in terms of critical masses of people but on a smaller scale, about individuals and their relationship to themselves and others.

In the context of genocide, however, the meaning the production systems of the camera is less important to me. The camera is a primary way to document and distribute data. I can’t ignore the fact that the production and distribution of camera-made images in Gaza, for example, is one of the primary tools for solidarity and resistance. If anything, the camera in genocide can stand in for reality, where image production by the oppressed is direct resistance to their erasure and the erasure of the reality of genocide. I feel in response to the totality of the genocide in Palestine, a deepening disinterest in bourgeois-media-studies-camera theory replaced by a deep and immediate feeling of despair and disgust.

In ‘They Could Not Be Seen’, you probe rurality, loaded landscapes, and how camera-produced content moves online. What is the background of this project? Why did you choose Parler as your data source?

At the time I made the work, the first COVID lockdown, Parler was massive. The fact that their data was leaked in such an accessible way was shocking to me. The alt-right and Parler were fuelled in a lot of ways by libertarian ideas, ideas of survival preparation, doomsday prep, and the logic of escaping to the hills. The Parler data leak really exposed the pure ideology and aesthetics of this way of thinking. Every video uploaded to the platform could be geolocated to a specific GPS point on a map. If you were uploading in the city, you were quite hard to discern, as you are within a mass of information. However, if you ‘drank the koolaid’, so to speak, and were uploading to Parler from a rural place, you stood out completely. You could trace single uploaders in minute detail, where they lived, where they would go, and when they would upload, completely disarming this primitivist fantasy that rurality offers some kind of escape.

I saw this as another axis of extractivism enacted in Scotland. ‘they could not be seen’ sets this far-right extraction against the literal extraction of mining and the places where the mining industry has now left. These two extractions, the libertarian who seeks to gain ideological safety and the open-cast coal mine, are the same, and their end result is just as damaging.

I think to bring this work into the present, we now live in Parler. With Trump reelected alongside Elon Musk, ‘X’ is now Parler, and Parler is now mass media. I recently reinstalled the work on three Dell computer monitors set on the wall, mimicking military command screens, the desk of the idealogue poster, and the cab of the dump truck, which brings actual death to the piece. I think, for a moment, the work felt like it was responding to a specific time, a particular system of belief, that had passed. But I think it becomes clear as time passes that the work, and Parler, was the root of something that has won, the beginning of a serious solidification.

The phrase ‘loaded landscapes’ suggests a tension or complexity within the places you depict. What kind of ‘load’ or significance do you see landscapes carrying in your practice?

In many ways, I think ‘missing in-crypt tides’ was the conclusion of many years of practice. I believe that with any larger piece of work, there is a death that comes alongside it, a resolution of a way of thinking. Whereas before, the fractured complexities of the land in Scotland felt really important for me to hold, but I find myself increasingly leaving that behind. Now I’m thinking more about the literal ‘load’—the freight train packed with tonnes, the pressure the track enacts on the earth underneath it. I guess here I feel myself leaning towards more expansive thinking around infrastructure.

I recently took part in the FieldArts residency with the Infrastructure Humanities Group here in Glasgow. I found their way of thinking and the broader approach of Infrastructure Humanities to be a useful hybrid structure. Thinking expansively about infrastructure, how its function informs its meaning, and how infrastructural thinking can be a radical form of cultural critique and making.

‘missing in-crypt tides’ highlights a symbiotic relationship between the body and technology. How do you see this relationship evolving in the context of contemporary digital culture?

This was one of the core axes I wanted ‘missing in-crypt tides’ to dwell in. I was thinking about paranoia and death, about the desire to reach through the screen, to look deeply into the eyes of the other. I think of how existing technologically morphs us, in particular for ‘missing’. I was thinking a lot about true crime and the ‘incase I go missing binder’, a TikTok product people were buying to anticipate their eventual abduction. In your ‘incase I go missing binder’ you include DNA samples, an array of pictures of yourself, possible suspects, possible motives, and clues that will ultimately solve your future case. It’s fascinating, this anticipation, this re-performing of the aesthetics of true crime, this almost excitement for your turn, for your body to be made media, to be solidified by thousands of TikToks speculating on your disastrous fate.

There is a middle ground, a tension in your body, that comes from trying to inhabit media, and it is nauseating. When I made the piece, one of the stories in my head was about somatic illnesses. During the pandemic, there was an uptick in the isolation of people presenting to epilepsy clinics with symptoms [1].

As real as these symptoms were, they were not medically consistent with epilepsy. People were watching epilepsy content on TikTok and then embodying symptoms and tics that they saw to such an extent that they had a functional, if socially produced, form of epilepsy. Stories like this are often used as scaremonergy sort of stupid technology pieces and often have an ableist and anti-youth undertone, and I’m not remotely interested in that.

With the somatic disorders, the human aspect fuels me. There is a deep desire to embody something, to make the interaction with technology real that your body shapes itself and re-performs an illness. I find this incredibly powerful, beautiful, and tragic. So yeah, I find this tension between ourselves, our bodies, and technology, which I only see increasing, really interesting. In ‘missing’ the vocaloid, Elanor Forte came to take on this role, somewhere between fandom, the machine, and feeling.

What’s next on the horizon for you? Are there any new projects or themes you want to explore in your upcoming work?

I want to work much more with installed moving image, especially using specific screens and objects with their own connotations and logics, like my piece ‘failsafe backup’ (2023), which sets a continuous extreme zoom on a digital rearview mirror.

The TikTok trend ‘no borax no glue’ has been unshakable for me. In this trend, you would ask for something impossible (‘how to bring back my dead mother no borax no glue’). Here, ‘no borax no glue’ is a longing for what you know can’t exist. This comes from YouTube, kids searching for slime-making videos— you can’t make slime without glue or borax, two things a child is less likely to have to hand- hence the search phrase ‘how to make slime no borax no glue’. On TikTok ‘no borax no glue’ is a stand-in for that impossible desire. It speaks to a longing, a search for the impossible, an angsty desire that I think is just soaked through the bones of technology. Maybe this axis is where we can recover from the deep financialisation of our emotions. I love ‘no borax no glue’ for its connection to old YouTube slime-making videos and for its nod to wider extreme and vast infrastructural realities, like the mining for the material borax (boron) itself.

This thread is still unravelling, but it has led me to the old youtube tutorial (esp. the voiceoverless textpad genre) and general ‘schizo’ posting (esp. sonic paranoia), amongst other places. Again, as I mentioned earlier, I want to probe some kind of map of deep feeling, of extreme manifestations of technology and belief. I think somewhere in the connection between these things is my next work, and I’m just in the process of letting them connect. As part of this process, I’ve also been implicating myself by beginning to post really, very, very loose sketches and stuff thrown together on TikTok. You can find me at @hallaig if you are interested.

What is more important: to take or not to take yourself too seriously to be creative?

Seriousness is such an important axis in these conversations. But I do think we live in serious times— in times of deep distance where farcical, deeply unserious technological realities have very serious impacts on people and power. For me, this axis requires hybridity. Gen Z does this well; it is always serious and unserious at the same time. Marx says that history happens first as tragedy and second as farce. We are in farce, technological and fascistic farce. To meaningfully respond to this state, you must take the unserious seriously, and I guess I try to cultivate that.