Words by Lula Criado

Molecular biology is a branch of science that analyses the role of DNA, RNA and cell function, aiding our understanding of biological activity, in particular, genetics. In the early 1990s, the traditional knowledge of molecular biology and genetics changed with the development of biotechnology, computational systems biology and genetic techniques such as PCR.

Artist and geneticist Dr Hunter Cole utilises her knowledge and experience in biotechnology to create digital art, installations and drawings that challenge what we understand (and know) about biotechnology (and science).

In her pioneering project, Radioactive Biohazard, the advanced progress of biotechnology is the artwork itself. Dr Cole raises awareness about the relationship between biology and art, as well as between (bio)art and society by confronting issues related to human cloning, stem cell, DNA tests and the human genome project.

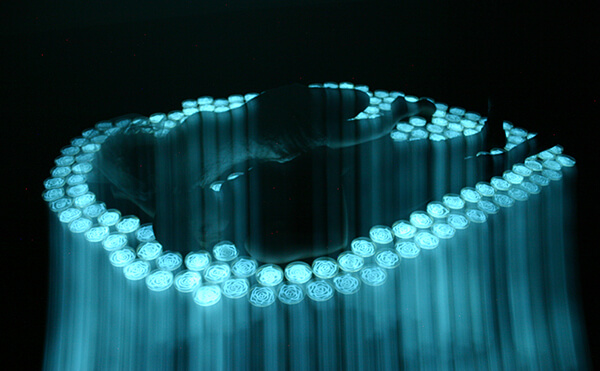

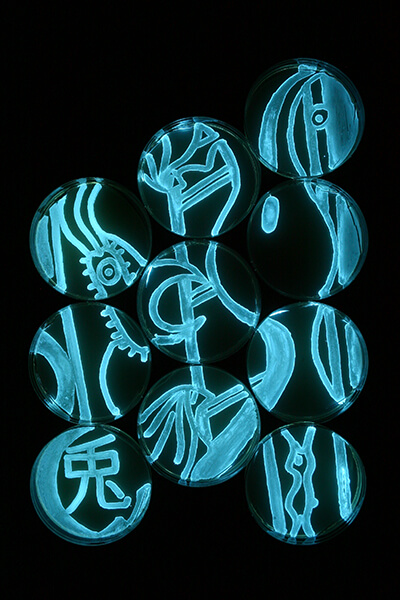

Later, Dr Cole developed Living Drawings, a groundbreaking project in which she blends different types of artistic expressions such as sound and drawings with bioluminescent bacteria cultivated in Petri dishes. As well as photographing the bioluminescent bacteria in darkness, Dr Cole created music based on the protein sequence of the bacteria.

The beauty of the biotech-based creative universe of Hunter Cole is that it is not only art but science also. Our culture often focuses on the ethical implications of biotech.

However, her work emphasises the benefits of biotechnology and connects audience, art and science, allowing us to reflect on the applications (and implications) of biotechnology from a positive perspective.

Dr Hunter Cole explains, “Science provides new technologies, new materials and other resources for use by artists. Creativity and art can lead science to look at matters differently.”

You are a visual artist and a geneticist working (and teaching) in the intersection of art and science. When and how did the fascination with art/science come about?

I am an artist. I have a need to make art. While my educational background and training is mostly in science (genetics and biology), I often use art as an avenue for teaching students about science.

Growing up in San Francisco, I visited both art and science museums as a child — almost every week. I was immersed in an environment of art and science. Even during my undergraduate work in plant genetics at UC Berkeley, I was a photographer and created drawings.

I became more serious about making art during my work in genetics in graduate school at UW-Madison. Research and working in a lab (in science) can be frustrating.

This, combined with a timely trip to Paris led me to re-focus on my art. The art I saw in museums there inspired me and re-energized my drawing and painting interests.

I returned with new inspirations of combining art and science themes in my art, including the use of digital media, installations, and incorporating bioluminescent bacteria in my art.

In the early 1920s, the Cubist movement in art helped physicist Niels Bohr determine the quantum theory when he compared the behaviour of electrons with cubist paintings. In your view what is the contribution of science in the arts?

Science provides new technologies, new materials, and other resources for use by artists. Creativity and art can lead science to look at matters differently. This sometimes leads to new discoveries, new ideas, new methods, or new outcomes — in science and in art.

In my work, I use bioluminescent bacteria to produce drawings on Petri dishes and photography with bioluminescent light. I have incorporated a variety of scientific concepts, and political, and ethical issues in my art, such as human cloning, evolution, and biological warfare.

One of my paintings is based on important scientific discoveries in Dr Neil Shubin’s work looking at the tiktaalik as the missing link between land and water animals.

Is art helping understand scientific issues or it is challenging what society understands about them?

Both. Art challenges society’s understanding of science, as well as, what we think about directions or research in science. My art includes topics that challenge our thinking about subjects like human cloning, biological warfare, or creating of genetic children of same-sex couples.

Scientists have created offspring from two female mice, resulting in a fatherless mouse. In my art I frequently try to educate viewers about “real science.” Through my art, I’ve offered information about evolution, malaria, and endosymbiosis. My current project focuses on endometriosis.

What are your aims as a bioartist and a geneticist working in between science and art?

As I stated, I am an artist and a scientist. Art should stand on its own. Using art and science, I can foster awareness about important topics (through art). I am currently engaged with two projects including a photographic series of bioluminescent weddings, and my Life with Endometriosis initiative.

In these projects, I am continuing my focus on art, science and societal issues. Endometriosis is a disease where endometrial tissue grows outside the uterus in other parts of the body.

This can cause extreme pain and infertility. One in ten women have endometriosis. But most people have never heard of it. During the summer of 2015, I worked at SymbioticA on the campus of the University of Western Australia (Perth).

Using advanced scientific equipment, I created time-lapse micrographs of endometrial cells growing and dying. SymbioticA is the first research laboratory of its kind that enables artists and researchers to engage in wet biology practices in a biological science department.

Through my Life with Endometriosis project, I hope to bring greater awareness about a condition that affects so many women.

If you could visit a scientist’s mind, who would it be and why?

Rosalind Franklin. In 1953, Franklin was engaged in research that resulted in data to help explain the structure of DNA. James Watson and Francis Crick used her data — without her permission — and figured out the structure first. Franklin undoubtedly would have figured out the structure of DNA, on her own, given a little more time.

As a woman scientist in the 1950s, Franklin faced many difficulties and did not always receive recognition for her accomplishments. Tragically, Franklin died prematurely in 1958 at age 37 due to cancer.

James Watson, Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins shared the 1962 Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine for the discovery of DNA structure. In my own artistic attempt to credit Franklin for her work, I created a large digital art collage entitled, “Rosalind Franklin and the Discovery of DNA Structure.” I believe she deserves more recognition for her accomplishments and contributions to DNA science.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Nothing, really. I suppose every artist would like more time to create his or her art.

You couldn’t live without…

Travel. My family. And, of course, paper and a set of pens for making drawings!