Text by Natalie Mariko

As a young writer living in the West, there are certain poets one comes into contact with less as an introduction to a discipline and more so as a rite of passage. Plath is one. Keats, perhaps, another. For me, the earliest book of poetry I can remember purchasing on my own was the collected works of Arthur Rimbaud. Each of these fulfils a certain poetic archetype. The suicidal confessional. The wasting Romantic. The wine-drunk flaneur. And poets, as a matter almost of tradition and painting here in the broadest of strokes, tend to use these gateway drugs as an ideological lodestar. Pick your poison because one doesn’t write to live. Writing, the poet yawps from the gutter, any writing worth reading, drags the knuckles of its soul against its prison walls and pounds the white page red.

For the Madrid-based, Colombian-American literary artist Ana Maria Caballero, this image of the poet as a martyr is a misconception she’d rather we abandon. And she has a point. Which other artistic discipline is so thoroughly wedded to the idea of privation and despair as poetry? Safeguarded institutional access and an antiquated dispensation for ‘purity’ have divorced the public profit of poetry in a way no other outlet would dare. The closest analogue, though in the inverse, might be music-streaming’s push to turn artistry into the auditory equivalent of wallpaper. But, even here, the world decries the exploitative depreciation practices of Spotify. Whereas nobody seems to care that many of the greatest living poets of our time cannot and have never been able to live solely off their craft.

Caballero, an award-winning author of six books, aims to turn the tide. Her works are multidimensional, existing as much within the tradition of poetic creativity as entirely tangential to it. She was the first living poet to sell a poem through Sotheby’s, a transaction usually reserved for art objects or the notebook ephemera of long-dead literati. Her works implement digital data inscription in the blockchain, as well as physical presentations which challenge the relationship between a poem’s creation and the reader or collector’s participation, interrogating the very value system we have in place for what are, at their best, impassioned works of emotional and artistic truth. It’s a provocation, and I believe it should give any poet cause for serious self-reflection. Why should the poet starve for art? Or, worse, do I have to get a job at Amazon?

Natalie Mariko: You work with a diverse array of media, meaning traditional interdisciplinary tools, creating objects, dance, video, etc., but also with Web3 innovations like the blockchain. But as I understand it, the grounding of that practice is text. How would you describe it? Do you see what you do outside of printed poetry as ‘poetry’, or is it something else entirely?

Ana Maria Caballero: I call myself a literary artist, which means I work with the written word in the context of contemporary art. This can take many different forms. For example, performance and choreography. It also means investigating the implications of text-to-image AI generation and how we’re using language in new ways through this technology to transform words into literal, visual objects. It can also mean recording experience in new ways, such as materialising lived poetry via digital and physical forms. Much of my work questions how we’ve valued poetry as a society and invites us to reflect on how we can take it beyond the page.

Natalie Mariko: Where does poetry begin for you? Is there a specific poem or poet you remember that drew you to writing?

Ana María Caballero: Sandra Cisneros and T.S. Eliot. These authors serve as bookends for my work. I love Cisneros’s straightforward, conversational voice; it’s cutting in its honesty. Then there’s T.S. Eliot’s crafted narrative, eloquence, mastery of vocabulary—but also intimacy. Both Cisneros and Eliot share a sense of intimacy. I think my work is relatable precisely because it is so intimate. I believe you access the universal through the personal and the transcendental through the mundane.

Natalie Mariko: You spoke about ‘recording experience’, embodying the poetic somehow. I’m particularly fascinated by your book sculptures. That sounds strange to someone hearing it for the first time, but what is a book ‘sculpture’?

Ana María Caballero: In my Book Sculpture series, I’ve taken the traditional book form and, working with a very special bookbinder, produced books as single-edition sculptural objects. Each of these books has one single poem printed 197 times in its pages. The digits in 197 will eventually converge into eight. There are eight books in the series—eight being a number of abundance. My Book Sculptures invert the value to scarcity ratio of the book to ask: If we call a book a sculpture, if we only create one, if we exhibit, price, and present it as such – can we value its content in a way that also honours the poet’s craft?

Each Book Sculpture has a unique ISBN and a table of contents.

Each tome also includes an MP4 of a single page turning as I read the poem, which is recorded onto the Ethereum blockchain. The digital wields something the page cannot: voice. There’s also a text-only inscription of my poem on the Bitcoin blockchain. Ethereum allows heavier, bigger files to be recorded. Bitcoin is more expensive and complex to manoeuvre, but it does allow greater flexibility in terms of inscribing text.

Bitcoin is the mother of all blockchains, the oldest, most famous, most reliable one – it’s a compelling way to record our poems, to resist erasure.

Natalie Mariko: Somewhat related to this notion of voice, uniqueness, and the immutability that digitalisation offers—a lot of your work either indirectly or directly addresses the role and experience of motherhood. And the care with which you attend the presentation of these objects, poems, performances, and video works seems somewhat of an extension. To what extent has the experience of being a mother changed or informed your approach to creativity?

Ana María Caballero: My published books accompany specific moments of my life. My most recent one, Mammal, accompanied the experience of pregnancy and birthing. But my newer manuscripts are about very different things.

I became obsessed with trying to understand and describe motherhood in a way that felt honest to me. Many of the poems I’ve digitised or turned into more conceptual artworks come from Mammal—which was the closest one to the body, to the flesh when I began working in the digital realm. Women around me didn’t seem to be honest about their similar experiences. I felt very lonely. I poured this solitude into my book. All the words I couldn’t speak were spoken into the book. Now, many women say, “Thank you for saying that; I feel so seen.” The conversations I never had before, the ones I needed back then, happened at a later date because of my book.

Natalie Mariko: You’re drawing from Mammal for your upcoming solo exhibition, ECHO GRAPH, which opened at Office Impart in Berlin this month. Is that correct?

Ana María Caballero: My exhibition, ECHO GRAPH, presents one poem in myriad ways to explore how the medium through which verse is experienced affects the meaning it conveys.

I wrote the poem the day before I gave birth to my first child. I was living in Bogotá, Colombia, and I was 39 weeks pregnant. I went in for a sonogram, and the ultrasound guy said, “Your placenta has stopped working. Your baby’s losing weight. It needs to come out tomorrow.” But I felt great. I questioned his verdict but wasn’t brave enough to resist it.

I was induced, the baby’s heart rate dropped, and I ended up with an emergency C-section. Then they realised the placenta was fine. The guy had messed up the baby’s measurements. It was all unnecessary. I’d been preparing to have as natural a birth as possible and felt robbed. The poem doesn’t address this because I wrote it before I knew how things would turn out. This exhibition is a way of healing that trauma.

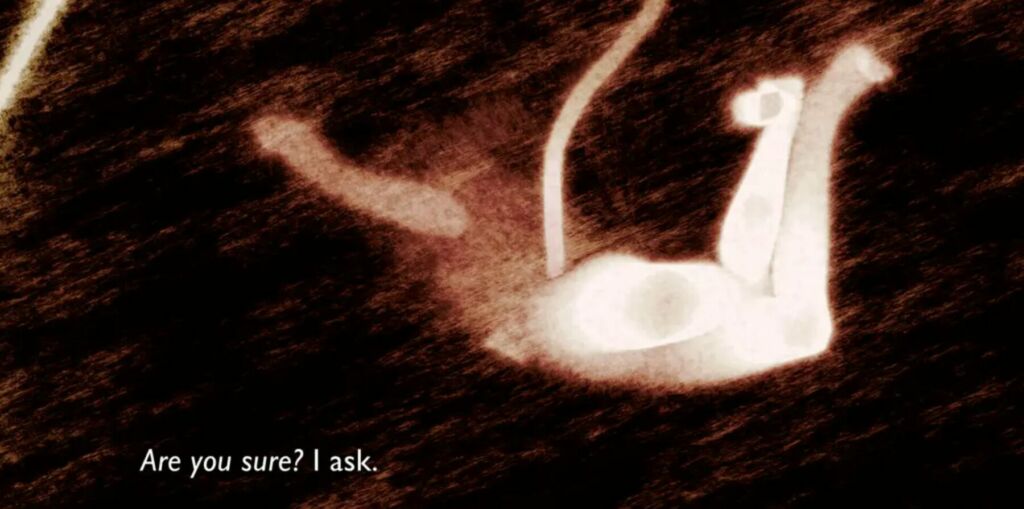

In the show, I present a choreographed video work in which I’ve put myself inside the womb to take back that space. I strapped on a motion-capture suit and worked with Mad Arts Studio to record my movements and insert my body into a womb-like setting.

From the video work, I took stills that represent meaningful snippets of the poem. For example, the doctor told me, “Don’t worry, the body fails all the time.” This moment is transformed into this verse: “Such physical failure/A not uncommon thing,” which is a diptych in the exhibition.

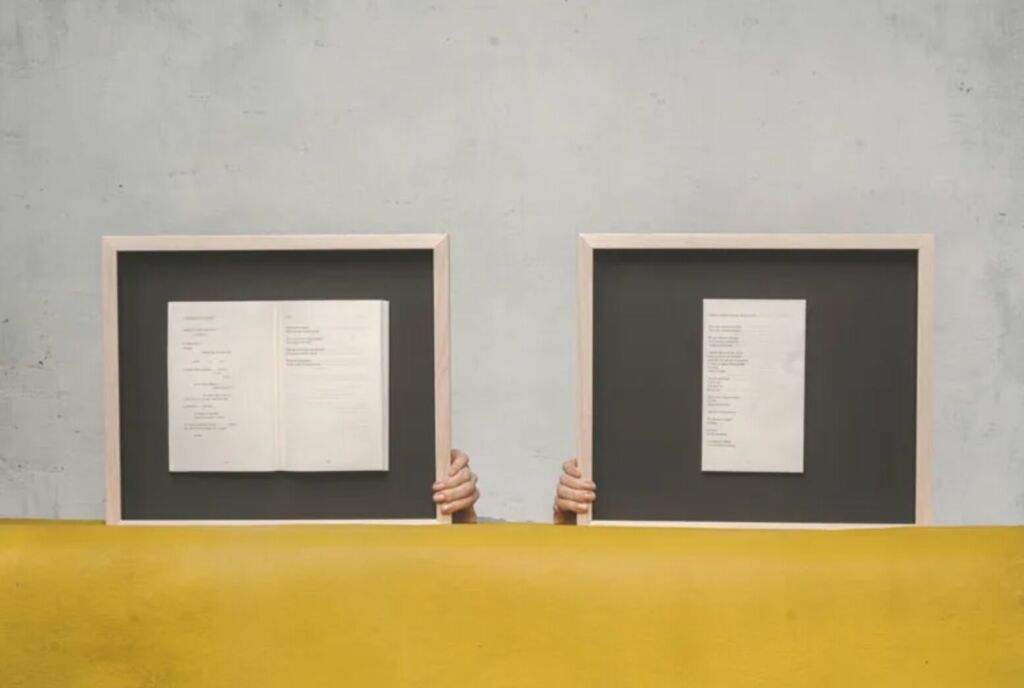

For the first time in Berlin, I present a new conceptual series called Page Break, where I slice a page of a poem from my “normal” book and then frame both the page and the book that once housed it. The work symbolises the act of taking the poem beyond the book and giving both the book and the poem the reverence they deserve by framing them side by side.

There will also be a Book Sculpture of the poem.

I want to invite people to consider what it feels like to experience the same body of language through various sensory inputs—page versus video versus sound versus choreography versus fragments.

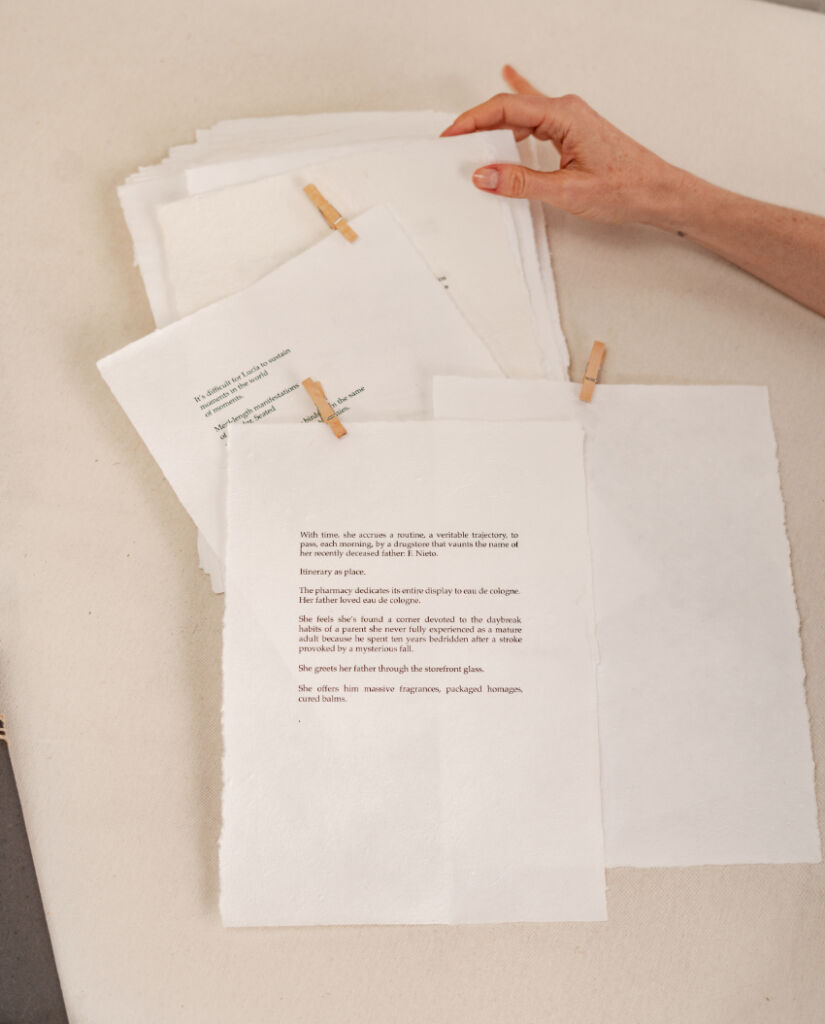

Natalie Mariko: That’s an incredibly generous answer. Also, it’s such a generous and multivalent exploration of a single set of words. I love how it’s precisely ‘poetry’ in all the metaphorical explosion of interpretations one can take away. You’re also releasing a monograph during ARCO in Madrid—Ropa sucia (The Wash). Each page can be hung as if it were a piece of laundry as part of the wash. And every printing of the book is unique. It has a unique set of poems, and the reader participates in the meaning creation of the work, arranging it, pulling it out, and physicalising it. How do you envision your work evolving through that readerly interaction?

Ana María Caballero: The poems in Ropa sucia, my first artist book presented in partnership with S/W Ediciones, are taken from a new manuscript that is 155 pages long. 155 is a significant number because it’s an homage to Hopscotch (Rayuela), Julio Cortázar’s play-as-you-go book, hailed as the first hypertext novel. Hopscotch has 155 chapters as well. I love Hopscotch because it affirms my ideas of how readers and writers construct each other, how reading is a generative process.

You can read a book today and then tomorrow, and it will change. If you put 50 people in one room and give them the same poem, they will have a different experience. The writer doesn’t own or control that. I love drawing attention to this fact. How can you value one reading versus another? They’re all so special and intimate.

There are 12 poems in each packet, and each selection is different. The actual paper is made from my old sheets. It’s actually my wash. Ropa sucia will also include laundry clips, inviting their collectors to hang the poems as they wish, representing generative–yet analog–readership.

I’m also working with a coder who will visualise each edition as an unbound book, illustrated by photographic stills of a performative interpretation of one of the poems. This generative–and digital– visualisation of my poems and performance accompanies each physical artist’s book.

Natalie Mariko: I want to zoom in on the digital for a moment and go into blockchain. As a technology, it has a particular public reputation—the ‘crypto-bro’. People in the know understand the use cases for these technologies, but concomitantly, that association is a particular wariness in outsiders engaging creatively with the technology. It’s invigorating to see how you’re integrating it into your practice. I am also aware that you write regularly for Forbes. With all that in mind, I wanted to ask a very open-ended and possibly strange question. How important is the sales medium in creating fine art? And how do you see others being able to implement the tool? Because it remains relatively niche.

Ana María Caballero: I have a collector who worked high up in Apple. I asked him once, “What do you think Steve Jobs would have thought of this technology?” He answered, “I think he would have loved it. He would have gotten it right away because the blockchain is simply a new file storage system.”

Major upgrades to our file storage systems have proved revolutionary. During the Renaissance, wealthy patron families like the Medicis helped spur an artistic movement. But double-entry bookkeeping also played a role in the advent of the Renaissance. The blockchain is just a ledger.

There’s resistance because the technology seems complex to use. But we all had difficulty figuring out smartphones at one time – or printers or fax machines. When the Internet started, and all these Silicon Valley companies appeared and disappeared in the blink of an eye, there was resistance to the web, too.

Whenever I hear an artist say, “I hate NFTs”, I respond, “Do you hate USBs? Do you hate folders?”

Natalie Mariko: As I see it, one of the traditions of poetry is recitation, quotation and public performance. We can go back to Ancient Greece. Amphitheatres are open-air spaces where rhapsodes and actors would come and sing from the Iliad, perform from Aeschylus, and so on. What I see as a differentiation, coming from that tradition and looking at NFTs and the blockchain, is that—you have these ‘digital originals’. They’re unique, single copies. And poetry is, from one perspective, a public good. Should poetry be a private property? A fine piece of art, a vase owned by an individual, a sculpture?

Ana Maria Caballero: The beauty of digital ownership is that one unique token certifies that you are the holder of it, but the work can exist anywhere. It can be on the Internet. It can be on a laptop. It can be on a phone or Instagram. For example, I have work going up for a Christie’s event at the Rosewood in Madrid and that same work will be part of an opera festival in Norway. This work is owned by a wonderful German collector based in Lisbon. This work has one certificate with one owner, but it lives everywhere. And the poem is also the title poem from my book, Mammal, which you can order on Amazon.

When we trade a poem with our mom, sister or anyone we love, we’re affirming its value. When someone trades a poem through a financial mechanism, they also assert its value and prolong its life. If the transaction helps sustain the poet’s work, the poet will have more freedom to create. There’s no reason why a work would become less accessible to the public if it is supported financially through digital ownership.

Natalie Mariko: There is this particular notion that comes along with poetry, a type of rebellion or outsider-ness, an emotive quality. Whenever I speak with people and say I’m a poet, they say, “I used to do that when I was a teenager. I would write it in my journal.” Like it was some sort of pubescent affliction. Like you grow out of poetry. I appreciate that you care so much about the value of poetry in this very public way.

Ana María Caballero: Humility is always important, but sometimes it’s confused with self-punishment. The subtitle of my book, Mammal, is: “Sacrifice is not a virtue.”

When artists go to school, they’re told: “It’s hard, but you might make a living from this.” Every craft puts forth the notion that if you get good enough, you’ll make a living.

But not poetry. Of course, it’ll be hard. Of course, it’s not easy. But at least there should be a possibility of sustaining our lives from our craft. Creative writing programs should offer poets more options.

I get sad whenever I give presentations, and people say, “Poetry is too valuable to be valued. Is painting too valuable to be valued?”

Natalie Mariko: I had a university professor. He was a fantastic, eccentric man—as many poetry professors are. One of the things he told us in the seminars was, don’t ever expect poetry to make your bread. It’s a resonant point. There is such an inherent value in sharing poetry and reading poetry. It affects us in such an emotive and personal way. And why shouldn’t that value be transferable. Can you tell me about theVERSEverse?

Ana María Caballero: I felt that traditional publishing was so lonely, so insular. You work for months, years, trying to get a poem published and then you do, you have no idea who’s reading it. There is little sense of communion, unless you’re part of an MFA program.

I began sharing my work through social media, such as Instagram and Twitter, and started to feel a sense of community. When I read about Web3, it made sense to me to upload the files I’d already created to these Web3 platforms, which would record my work on the blockchain. But I also wanted to create a gallery—a digital poetry gallery—where not only my work but also the work of those I admired would be shared.

A lot of my professors were my guinea pigs—Campbell McGrath, Denise Duhamel and Julie Marie Wade are all part of theVERSEverse. We’ve exhibited their works everywhere. I bought the domain in the supermarket parking lot!

Natalie Mariko: What’s something you couldn’t live without?

Ana María Caballero: I can’t live without pen and paper.

Natalie Mariko: What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Ana María Caballero: I think that lack of faith in our own ideas can be a cruel enemy of creativity. Sometimes, we’re too afraid to take risks, to veer, to affirm. Insecurity threatens creativity, but that’s only because creativity can silence insecurity.