Interview by Lula Criado

The creative universe of interdisciplinary Canadian artist and researcher WhiteFeather encompasses life sciences and engineering to create cutting-edge projects using materials such as human hair, living organisms or found flesh and bone.

One of her assets is to investigate the functional, artistic and technological uses of bodily matter through a wide range of supports, media and biotechnological techniques that overlap with the field of biomanufacturing.

WhiteFeather —artist-in-residency at the Pelling Laboratory for Biophysical Manipulation (University of Ottawa) and at Fluxmedia Lab (Concordia University)— aims to make scientific practices more accessible through artistic representation. With projects such as Biomateria and Crafting Biotextiles she investigates the interaction of biological systems, textiles techniques and tissue engineering.

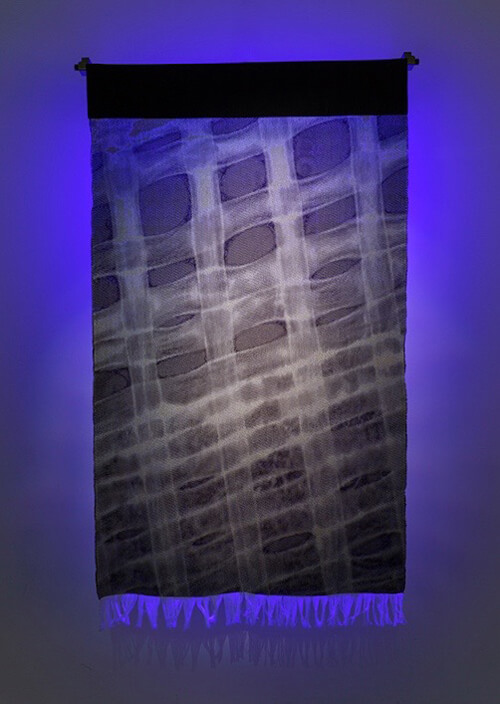

Crafting Biotextiles is a research-creation residency project developed at SymbioticA (Perth, Australia) in which wet biology and creative crafts techniques are overlapped to develop textiles patterns.

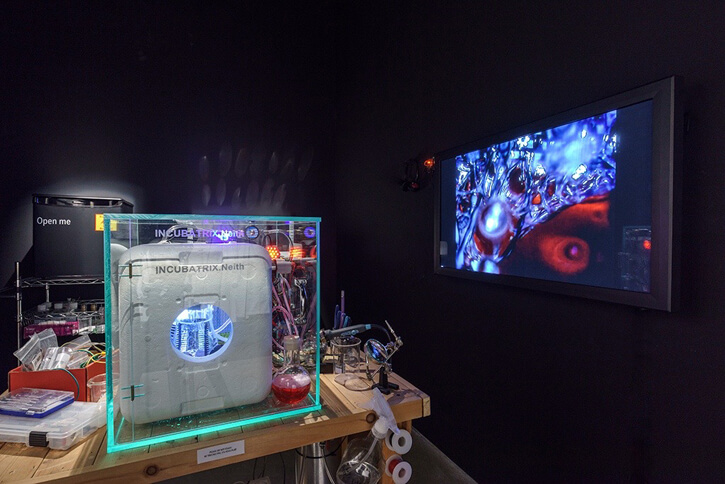

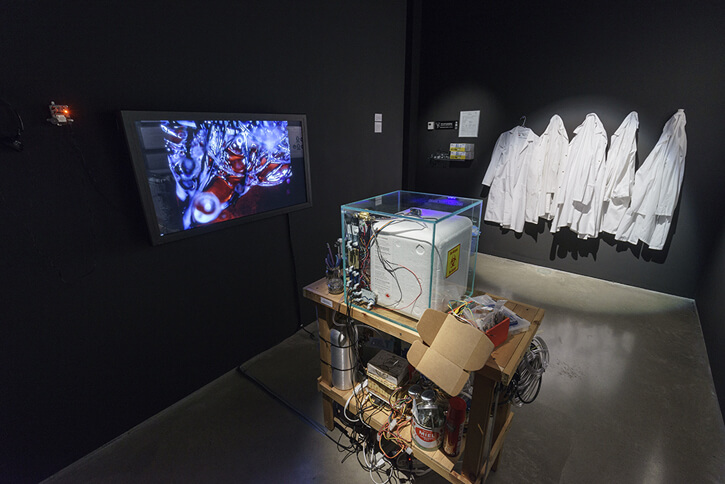

On the other hand, Biomateria, a mixed media and digital installation, blurs conceptual and practical frameworks to explain the relationship between mammalian cell lines and textiles through hybrid works that become the message. For Biomateria, WhiteFeather engineered biotextiles patterns in Petri dishes seeded with human bone cancer and cognitive tissue cells.

The conceptual framework behind Biomateria includes the work’s physical, political and cultural significance to raise awareness about political and ethical questions related to BioArt.

Biomanufacturing and, more precisely biotextiles, include aspects of bioengineering and biochemistry, among others, to modify living organisms to create textiles, vaccines or biofuels for human purposes but in the hands of WhiteFeather biomanufacturing becomes a strategy to explore new ways of thinking.

You are an artist/researcher working in the intersection of art and science. When and how did the fascination with biological systems come about?

I have a long-standing interest in bodily materials in particular, and in their inherent properties. As a textile artist, my interest in systems is rooted in my interest in materiality—how materials behave, form, and react and how those properties can be exploited for art-making purposes.

These characteristics may or may not necessarily be systemic, but they do extend to, and from biological systems. For example, most of the fibres I work with in creating biotextiles are natural fibres, such as human hair, horsehair, silk, linen, intestine, etc. Each of these fibres, generated through their own biological processes, possess certain properties that interact with and influence the cell systems I pair them with, creating a new ‘life’ system.

I’m also deeply interested in ephemerality and creating nonrepresentational works with a life span, including a process of deterioration. I’ve always worked with materials that break down, a comment on life/death cycles and a resistance to the museumification of art and culture.

Cell culture provides a perfect medium for accomplishing this kind of goal because it is difficult to present in a gallery context and impossible to maintain indefinitely.

In the early 1920s, Cubism helped physicist Niels Bohr to determine the quantum theory when he compared the behaviour of electrons with Cubist paintings. But, in your view, what is the contribution of science to the arts?

Certainly, abstract thinking is useful for formulating new ideas through reimagining data. Many artists and scientists are experts in abstract thinking and the conversations between artists and scientists can be extremely fruitful for both.

This has been my experience. Artists have long been interested in forms and systems, and in finding unconventional ways to reinterpret, recreate or augment them. Science essentially does the same thing. Though their methodologies may differ, I don’t see much of a fundamental difference between the two disciplines.

Considering the “contribution” of a discipline seems almost a way of quantifying or qualifying its merit, which I’m a bit reluctant to do.

Bioart blurs boundaries between art and bioscience to explore laboratory practices as an artistic medium. By doing this, is bioart helping understand scientific issues/practices, or is it challenging what society understands about them?

I don’t know if I’m fully interested in the agenda for helping, though I am an educator and am interested in pedagogy. I’m interested in making closed scientific practices accessible through artistic presentation.

It’s just that I’ve seen the “helping understand science through art” agenda used for propaganda purposes by biotech investors and I’m therefore critical. Art is a powerful channel to the subconscious mind, and a method for stirring up rigidly held beliefs.

I see it as a tool for challenging our understandings of ‘what is’ or what we take for granted as ‘real’. I think that some of what constitutes commonly-held ‘scientific knowledge’ may be just as much a cultural product as any work of art.

I’ve noticed that something that (non-scientist) participants in popular culture forums, such as online forums, sometimes forget that science as a discipline and practice is about questioning hypotheses and theories and challenging them to see what holds up. It doesn’t present absolute truths, though culturally, we seem to think so.

Art does the same – presents more questions than answers. Art might ‘help’, I think, in insisting that we check our shared scientific ‘truths’.

Biomateria spans between textile techniques and bioscience laboratory practices such as tissue culture and bioengineering. For scientists, one area of ethical concern is how to dispose of the living tissue at the end of an experiment. What ethical/philosophical issues arise in using living systems to create these biotextiles/biomateria?

For me, the act of disposing of a tissue sample at the end of an experiment is no more an ethical consideration than cutting up a head of hydroponic lettuce for a salad. These are manufactured biological materials within artificial environments, and have no capacity, that we know of, for pain and suffering.

Disposal isn’t the ethical question. For me, one ethical question concerns the contents of the nutrient media used in cell culture, derived from a burgeoning meat industry.

I’m not vegetarian nor against meat consumption per se, but anything with industrial implications is, I think, potentially fraught with exploitative practices. This is where interesting ethical discussions around biotechnology can happen, invoked perhaps by artistic works that point to them.

What are your aims as a bioartist working in between scientific methodologies and art?

There’s an intricate relationship between textiles and biology, both historically and now contemporaneously as the biomedical textile industry joins the current biotech boom. My interest as an artist is in exploring the areas of overlap between the two practices, including practical and theoretical overlaps.

Philosophically, how does the concept and presence of ‘intersections’ (as in woven structure) stabilize a form on a biological level? How does it disrupt our understanding of cell morphology? How can use of histological stains for enhancing specific proteins in a cell, impact or influence the way we dye our clothing? Those are just a few examples.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Impostor Syndrome is the enemy of this kind of creative working between disciplines, art and science. As an artist, when I do receive recognition for the merit of my science-based work, I feel like an impostor because I identify myself primarily as an artist. I don’t have a formal science background.

I do feel that my technique is solid through practice in the lab, and my hypotheses are grounded in philosophical theory and scientific experimentation, yet I often feel like an impostor in the world of science and as a researcher. This feeling, partly internal and partly because of some external suspicion I’ve encountered, definitely has impeded my creative progress with projects at times.

You couldn’t live without…

Writing and travel, two of my methods of exploring interiority and exteriority.