Text by Rola Daniels

Augmented Reality (AR) is one of several technologies emerging for widespread use, culturally popularised to undoubtedly soon be woven into the fabric of everyday existence. It is defined as a real-time direct or indirect view of a physical, real-world environment that has been enhanced or augmented by adding virtual computer-generated information. Falling into the broader category of mixed – or mediated – reality, it combines real and virtual objects registered in 3D.

AR also extends to diminished reality, whereby virtual information seamlessly blends over a tangible object to give you the illusion of absence. It is intended to enhance the perception of – and interaction with – the real world. Perception in this context includes sonic and haptic perception. Unlike Virtual Reality (VR), AR does not wholly immerse the user in a virtual environment but superimposes virtual objects and cues in real-time upon the real world via a viewing device. Not restricted to a headset or light, it directly consolidates the senses.

We must therefore open up a dialogue around how artists can use technologies like AR to challenge its everyday facilitations. Its artistic potential extends far beyond the visual image (its creation and manipulation) to enter the remit of issues surrounding the network and informatics, bio-enhancement, and vast identity formations.

Much of the scope of the discussion around AR is limited to visual acuity – i.e., the clarity of the image – and temporal synchronisation; both critical issues for artists, however critically limiting. However, with its growing quotidian use comes a responsibility to avoid a superficiality inherent to commerciality: a superficiality that overindulges the senses and leaves the imagination deserted and unfulfilled.

Artists must marry these rapidly changing technological innovations and their aesthetic integrity without it merely being ornamental or a spectacle. As a result, AR is prone to technical uniformity and corporate homogeneity as a commercially viable entity.

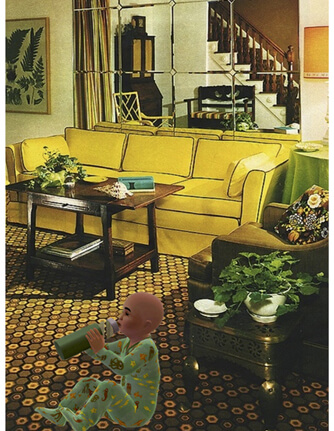

Artists, particularly performance artists, can use AR to challenge pre-existing physical and virtual space conceptions. As the very essence of AR is mixing realities, we are no longer circumscribed to the screen in our experience of virtuality. The superimposed layers of media (the still image, moving image and text) ‘have various scales and dimensions within one master frame’.

This complex framing and layering create a transgression between spatial perception and conception. For example, whilst we use mobile phones as AR viewing devices, a screen frames the video image, yet the information layered on the image simultaneously lacks a frame.

AR technology operates through the necessary convergence of space and time; however, its spatial configurations are increasingly mobile. Technology creates a paradox if we understand performance space to be both stationary and portable. It is a form of mnemonic spacing – it needs spatial stability to add the temporal layers – yet it is designed to be transportable.

A performance that travels would have to consider how to use metadata to inform images to adapt to multiple spaces; however, a version in a single location might contemplate avoiding the kind of technological uniformity seen in perfect reproduction – losing the subtle fluctuations of live performance. The geo-tagging used in AR conceptualizes and compresses space and time antithetically to create disembodiment and a lack of synchronisation.

This is problematic for performance because there often is an assumption and perceived reliance on other bodies, even if that body is a technology. So how does AR construct a new subjectivity in the threshold between physical and digital? This has been illustrated by cartographic screen displays that use maps crafted to contextualize space with Global Positioning Systems (GPS). Whether you are walking down the street or driving a car, you experience a disembodiment that subsequently occurs when the birds-eye view on the monitor alters perception – or if the technology experiences a glitch – due to physical and virtual resynchronisation.

Theorist Mark Hansen has discussed the extension of framing by technologies like AR through his consideration of ‘wearable space’. He writes that ‘clarifying the nature and extent of the coupling of body and space is particularly crucial in our coevolution with technology’: embodiment must be clear on what it generates informational.

He argues that, as seen in architecture, digital deterritorialization centres the body in a spatial framing of information. Performance space disrupts the repetition and rhythm of the virtual, addressing this challenge in mixed reality performances: the groundlessness of the digital helps to reconceive the relationship between the performer and the ground.

Spaces for performance have changed and adapted since traditional theatre stage layouts consisted of audience facing performer in a two-block formation by using, for instance, circular arrangements in which the audience surround the performer (Marina Abramovic’s The Artist is Present (2010) is a notable example of such a performance). AR technology forms another type of space outside the realm of gravity to blur/extend performer and reach, one that sits between the physical and the virtual and in which the audience will experience heightened body weightlessness.

Artists hold power and arguably are responsible for reinterpreting ethical guidelines and moral codes. In particular – how we perceive identity. AR technology is readily available on smartphone apps such as Snapchat, so several assumptions are already made by large tech companies about how users are expected to interact with it – the result is identity distortions through visual self-representations created by AR features and filters intended to enhance the image – in Snapchat’s case the selfie.

Artists can use technology to construct and reconstruct several identities that emerge, interact and reform subsequently. In this repetitive cycle, a technological gesture is born: ‘For any movement to become a gesture, it must be ‘representative’…repeated’. A unique act must be repeated multiple times to qualify as a gesture.

Creating new images for consumption in augmented art makes it possible to reinterpret pre-existing identities formed from uniform interactions with the technology. In the 1920s, Gestalt (translating from German into shape and form) psychologists studied the perceptual organization of complex scenes in our visual field. In this field, particular regions are grouped and segregated to establish meaning and content. They fundamentally identified ‘principles’ and mental cues that cooperated and interacted to coalesce our visual organizations.

In its broader potential, AR can enhance our cognitive capabilities and perception – if we are, for example, to use it for bio-senses that operate through interconnecting data. This could be materialized through bionic eyes that absorb a complete contextualization of our environment, including the expanded spectrum of light that humans cannot usually see. Accessing other frequencies could take the unknown into performance space, engaging our senses with one another and perhaps providing new information that would instigate the imagination.

This opens up several questions about anxieties surrounding technology that assumes human responsibilities, such as in debates around Artificial Intelligence (AI). Talk of bio-enhancing technology always treads lightly between positively enriching our lives and interfering with the purpose of our integral neurological wiring. Any cognitive enhancement we gain from the hybridisation of the digital and the physical in AR may defeat the essential human fallibility of using solely memory-based imagination – this is then counteracted by the consequences of not using human visual perception.

AR technology operates through central vision instead of peripheral vision, providing less accurate information on size and movement alteration. If we don’t use our peripheral vision enough – essential for depth perception and relative motion assessment – we risk interfering with and destabilizing our internal bodily sensors. Unlike having naturally impaired vision, there are no adaptive cerebral strategies from any aggravating repercussions of digital enhancement.

When Sartre wrote about the imagination, he separated it from perception, saying that invention takes over when we are devoid of the perception achieved through observing something. For performance, conjuring up images from their absence can often be intrinsic to a narrative.

As we enter the age of desiring ultimate virtual illusion, it is essential to ask ourselves whether indistinguishable photorealism is something we want or even need in live art forms such as performance and theatre.

Could AR visuals inhibit this process of imagination? There is, however, always going to be an ever-changing conception of realism with each age in reaction to technological changes. In AR technology, artistic integrity comes in its creation, wiring, design features and ability to function as a creative performer.