Words by Patricia Bondesson Kavanagh

Dr Charissa N. Terranova is a US-based writer and educator currently an Associate Professor of Aesthetic Studies at the Edith O’Donnell Institute of Art History at the University of Texas, Dallas. Throughout her career – from being a PhD student at Harvard to regularly contributing art critic and curator – Terranova has pursued alternative perspectives on the systems, both theoretical, biological and technological, within modern and contemporary art and architectural history.

The early stages of this pursuit can be traced back to her 2014 book Automotive Prosthetic: Technological Mediation and the Car in Conceptual Art. In it, Terranova explored our most popular mode of transport and the role it has played in conceptual art. Rather than rejecting analysis of non-traditional art objects, it directly confronts the complex relationship which exists between ourselves and our machines. Using critical and new media theory, it navigates the sophisticated network of relations which exist between art and technology.

But these systems need not be mechanical in nature; in Terranova’s most recent publication, Art as Organism: Biology and the Evolution of the Digital Image, where the system under scrutiny is biological. Further underscoring Terranova’s sustained interest in artworks not as disembodied objects but as components in an often interdependent matrix of meaning, it charts the influence of biology, general systems theory and cybernetics throughout 20th-century Modernism, particularly in conjunction with the digital image and early computer art.

In writing and practice, Terranova weaves a rich tapestry of theory, citing eclectic thinkers such as Donna Haraway and light-artist György Kepes as sources of inspiration, with which she can then probe the multiplex structures binding together visual theory, science and technology. In her upcoming publication Fearless Polymathy: Morphogenic Modernism in British Art-Science-Design, Terranova will navigate the heritage of Bauhaus ideas in the formation of biological and digital art practices during the 20th century.

As a writer and educator, one of your topics is the history of biology within art and architecture; when and how did your fascination with this subject begin?

The roots of my current work in biology are indirect but deeply located in my training in art and architectural history and theory. My first degree (1992) was in Art History. I spent the years (1989-1992) earning this diploma, happily memorizing slides and artists’ biographies and getting the basics of the field. But, I think I was never cut out to be an object fetishist – a connoisseur. I love art, design, and well-made things, but it is natural and intuitive. There is no challenge in this for me.

Doing advanced work in the field based on connoisseurship seemed and continues to seem simply too easy for any such advanced training. Why would I need to get advanced degrees in the field if it were simply about trafficking in class, taste, and marketplace values? …As this is the core of connoisseurship in Art History. My life as a serious thinker has always been about systems – complex systems.

In my second degree, an MA in Art History (1996), I started to think about objects in terms of systems, landscapes, and architecture. I identify this as the deep origin of biological systems in my work. Markedly moving away from connoisseurship toward complex systems, I wrote a 200-page MA thesis in 1996 titled “Space Alienation: An Investigation of Henri Lefebvre’s Theory of Social Space.” As one can tell by the title, I was (and continue to be) very influenced by Donna Haraway’s ideas about merging academic scholarship and science fiction.

This project started as an interrogation of Walmart and American urban sprawl in terms of Lefebvre’s ideas and the writings of French theorists like Jean Baudrillard and Paul Virilio. I actually wrote two versions of this thesis, one that was extremely theoretical and very much true to myself, a copy of which went off with my application to the PhD program at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, and a second version that was a deployment of Lefebvre’s ideas in the French suburban landscape, which I wrote to appease my committee members who were more hardline social historians. I ended up loving both versions: I am proud of both of these documents.

I was accepted to Harvard’s program (with the first very theoretical version) in Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Urban Form, and ended up, after about 4 years roaming the entrails of the Harvard library system, spending 2.5 years in France writing a dissertation about mid-twentieth century French public housing, les grands ensembles. I never published this 400-page tome, but these ideas – including those from Jacques Derrida’s Ecole des Hautes Etudes classes – are within in my blood. I will always arrive at what I am doing, at some level, through the lens of modern architecture and philosophy combined.

I came to Dallas in 2004 for a teaching position at Southern Methodist University and returned to the theory-frenzied person that I really am – the Walmart-French theory person – and started working on a book about cars and conceptual art, which was eventually published as Automotive Prosthetic: Technological Mediation and the Car in Conceptual Art (2014).

My work on biology and systems approaches crystallized here. In this book, I resituated the dialogue around conceptual art, moving it away from linguistics, semiotics, Structuralism, and Poststructuralism toward technological interfacing and mediation, cybernetics and systems, kinetic perception, theories of affectivity and embodiment, phenomenology, and post-humanism.

I located the origins of Conceptual Art in transformations of the greater mass media after WW II, focusing on the writings of Marshall McLuhan and Roland Barthes in the early 1950s and the groundbreaking exhibitions linking technology and conceptual art in the late 1960s and early 1970s, including The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age in 1968-69 at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, Cybernetic Serendipity in 1968 at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, Software: Information Technology – It’s New Meaning for Art in 1970 at the Jewish Museum in New York, and Information in 1970 at the Museum of Modern Art.

This book marked a big turn in my career, which is likely symptomatic of a greater paradigm shift. Simply put, I left behind postmodernism in Automotive Prosthetics. Very generally, the embodied-cyborgian perception and ubiquity of automobiles revealed to me the profound combination of fathomlessness and objectivity that is science and science studies.

Postmodernism had (mis)taught me that the multifaceted sciences were a uniformly suspicious and capitalistic Science. Thus, I could no longer have much to do with its credos of relativism and sectarianism. I sought, once again, in the spirit of Donna Haraway, a feminist objectivity, so I started reading books about genetics and rising postgenomics.

From this first book, oddly enough, Hungarian light artist György Kepes emerged as a lodestar and generative source of connections – across my work. My next book will be in part about him, and I am doing a symposium at my university about Kepes’s Vision + Value Series (1965-66) in the spring of 2018, which is funded by a grant from the Terra Foundation for American Art.

With respect to finding my way to Kepes, I was trying to understand how it is that two such disparate figures – the urbanist Kevin Lynch and artist/curator Jack Burnham – could sound so similar in their description of distributed networks and relationality. For both of them, the image is a set of distributed energies or points across time and space – it is a biologically sourced digital image.

These two men were both connected to Kepes and MIT. They worked with Kepes at MIT. And Kepes’s ideas about relations, connectionism, integration, emotions, tactility – and biology – brought me to Bauhausler László Moholy-Nagy, a wellspring of certain of Kepes’s ideas. This all led to Art as Organism: Biology and the Evolution of the Digital Image, which is about Moholy-Nagy, Kepes, Op Art, New Tendencies, EAT, and the CAVS at MIT.

One of your most recent books is Art as Organism: Biology and the Evolution of the Digital Image, in which you reveal the complex connections between visual culture, science and technology that comprise the deep history of twentieth-century art. In what ways has the use of technological developments as an artistic medium changed how we relate to science and art throughout the 20th century?

So, I will answer this question in two ways: first, in terms of how technology has transformed how we relate to science through art and second, how the omnipresence of digital technology and algorithms is cause for a recasting of the field of art history.

First – art has, for some time, been a connector to the world of science. It has been a powerful and unique tool for popularizing science. What I mean by “powerful and unique” is the way in which art has the singular capability of conveying scientific ideas without becoming a slovenly midwife to science – without simply illustrating the ideas of science. In the most successful instances, art-science-design projects present scientific information in morphogenic terms – that is, in emergent shapes, forms, and tableaux.

The morphogenesis results in an array of hybrid forms: sometimes in a wholesale critique of a given field of science, a fantastical extension of a given field of science, or an intriguing object that offers heuristics about a given field of science. This polyvalence is very special: it is a testament to the presence of “art” within “art-science-design.” Art-science design bears developmental (and here I mean embryological developmental) qualities: the unity of fields bodies forth several different opportunities in a given project, which is potentially world-transforming.

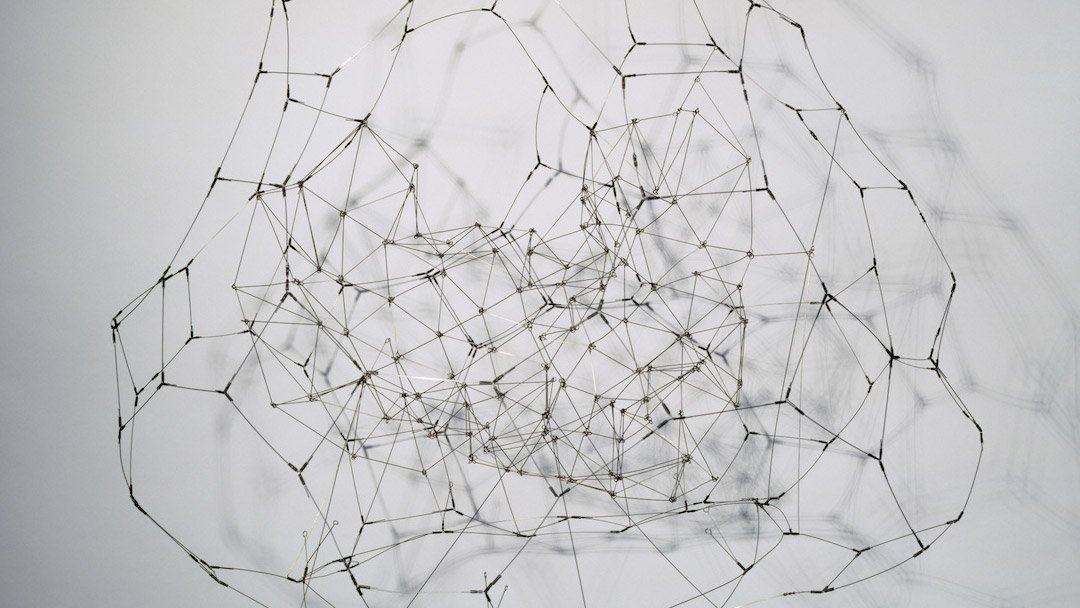

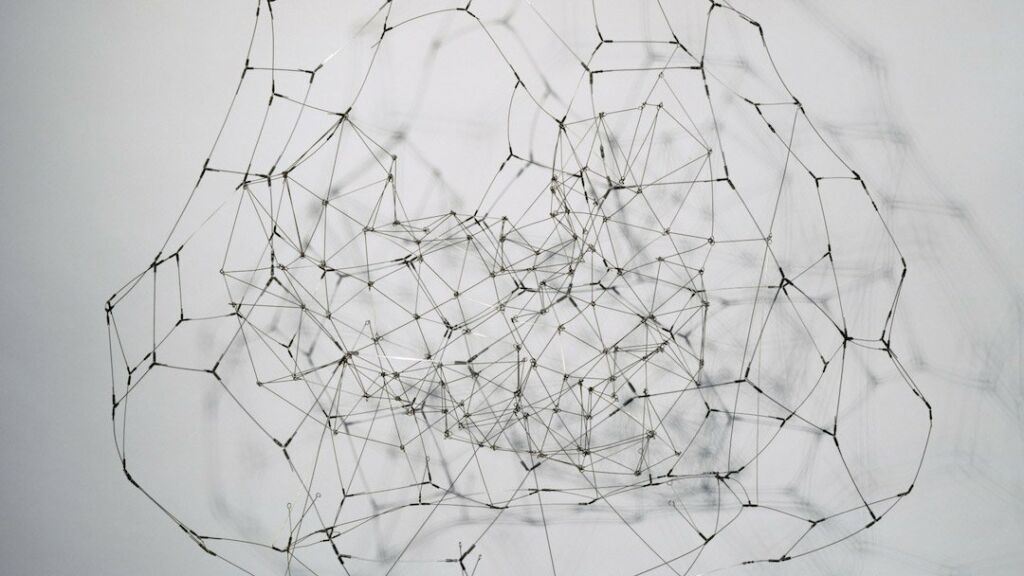

Related to this first response, I do think that the use of proto-digital and digital technology within art – the making of cybernetic brains from Norbert Wiener and Ross Ashby’s kinetic and responsive robots to Katherine Bennett and Meredith Tromble’s interactive environments – mirrors back qualities of biological life. Insomuch as artists using digital technology within their work are using complexity as a medium, they are using an approximation of life as a medium.

Second, the experimental work going on in art-science-design now, at this very moment, sends cascading waves of transformation backwards and forwards in time. Contemporary art-science-design practices, be they robotics, software, bioart, or bioarchitecture, call for the re-drafting of the field of art and architectural history to account for its existence – its always already existence (to be Derridean).

In the past, from our earliest examples of humans’ attempts to scratch out renderings of reality on cave walls to electronic immersion in 1991 with Dan Sandin’s virtual-reality CAVE. I am reworking the field through my courses at the university after these next two books are completed (Fearless Polymathy and an anthology on art, architecture, and D’Arcy Wentworth Thompson’s On Growth and Form (1917) I am co-editing with Ellen K. Levy) I would like to put my mind to writing a textbook on ASD, Art-Science-Design.

You are currently working on your fourth book, Morphogenic Moderns: British Art-Sci Polymathy in the 20th Century. Could you tell us a bit more about it and the intellectual process behind it?

I am impassioned by this book project – the title of which I have tweaked to Fearless Polymathy: Morphogenic Modernism in British Art-Science-Design. I have spent the last two summers working in archives in Edinburgh, St. Andrews, Norwich, Cambridge, and London. I have so many deep and resonant relationships in the UK: I feel like, if I have a spirit, it is sort of there, and not really where my body is in Texas. My life, at some level, is with my friends and colleagues in the UK.

This book is something of a sequel to Art as Organism, insomuch as both are about what I have been calling the “diasporic Bauhaus.” In this phrase, I name the tentacular nature of Bauhaus ideas, their outgrowth and afterlife beyond Weimar Germany, and how architectural functionalism morphs into biological and digital ideas and praxes within art during the twentieth century.

In particular, I am fascinated by – writing about – the growth and transformation of what began as the Gesamtkunstwerk, the total work of art of 19th-century Wagnerian origins, which is the living force in the original promise and mission of the Bauhaus that unfolds around “bau,” the idea that “bau,” or building, could contain within it a holism made up of the applied and fine arts combined. In the actual German Bauhaus (1919-1933), this quickly transmorphs into a curriculum rooted in functionalism, or the unity of art and technology and art science-technology.

Art as Organism tells the story of this unity within Moholy-Nagy’s ideas during and after his life. It follows the evolution of his biocentric take on light art and light painting in Berlin in the 1920s to Chicago and the New Bauhaus/Institute of Design in the 1930s. After his death in 1946, the work of Kepes and his many curatorial, art, and pedagogical projects at MIT up until 1975. This is but one story of the diasporic Bauhaus in the United States during the twentieth century. I imagine there are more…

Fearless Polymathy is, in fact, one more diasporic Bauhaus tale. It tells a parallel story but in the UK. It starts in the 1930s with what is variously called the British or London Bauhaus and the interactions between designers such as Moholy-Nagy, Kepes, Marcel Breuer, Walter Gropius, Wells Coates, William Lescaze and scientists (mostly from biology) such as Julian Huxley, JD Bernal, JG Crowther, J. Needham, CH Waddington, and LL Whyte.

It traces the efflorescence of art-science-design [ASD] as a field of practice and creativity across the twentieth century from the 1930s to the 1970s. The activities in Hampstead, London, at Wells Coates’ ISOKON building, the Tots and Quots meetings also in London, and The Theoretical Biology Club in Cambridge round out the first chapter. Chapter two focuses on the role of genetics and ecology in emergent cybernetic art and design in the work of geneticist Conrad Waddington at the University of Edinburgh.

Chapter three looks at the collaboration between artists and scientists at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London in 1951, paying special attention to the exhibition Growth and Form and the Festival of Britain. Chapter four frames the British origins of Leonardo: Journal of Arts, Sciences, and Technologies. The fifth chapter considers the interconnection between this journal and György Kepes’s Vision + Value Series and the related shift from first- to second-order cybernetics in the work of Gordon Pask and Heinz von Foerster.

Other figures who appear in this story include architect Justin Blanco White, modern painter John Piper, his wife, art critic and opera librettist Mfanwy Piper, German founder of the Bauhaus Walter Gropius, Canadian architect Wells Coates, owner of industrial design company ISOKON Jack Pritchard, educational visionary Henry Morris, designer Marcus Brumwell, painter and costume designer Yolanda Sonnabend, curator and art critic Jasia Reichardt, collector and art gallery owner Richard Demarco, and British Pop artists Richard Hamilton, Nigel Henderson, and Eduardo Paolozzi.

Each of these figures is a “polymath” because they followed their curiosities into new zones and ways of thinking. They did not fear exploring areas of expertise far afield from their own. They did not ignore, suppress, or sublimate inquisitiveness but followed it openly. The exuberance of heedless curiosity that is at the core of polymathy might be connected to the Indo-European etymological root of the second part of the word, “mathy,” which comes from mind-, to pay attention to, be alert, to be awake to. In essence, if we stay true to the word “polymathy,” we stay true to being awake to many things.

The book develops a contemporary theory of polymathy based on these twentieth-century figures working collaboratively in architecture, design, art, biology, and evolutionary theory. While a book about the past, its theme of “polymathy” bears grave importance in our present political economy, which privileges “life-long learning” and knowledge across and from combined fields. It provides a path from the past to the future. The book shows we are not alone; many have come before us, and we stand on the shoulders of giants.

Nowadays, with disciplines like biodesign, genetic architecture, biocomputing and synthetic biology, wearable technologies and techniques like 3D/4D printing, and programmable matter, it feels like the living and the digital are becoming closer than ever. Do you imagine a not-so-distant future where the digital will completely blend with the living?

I believe the digital is already blending with the living. All sorts of medical practices, most certainly pharmaceuticals and genetics, are driven by biocomputation – so we are already there. I have been a cyborg all my life, as I was born 6 weeks late (a 10-month gestation!) and lived the first days of my life in an incubator. Then there have been the antibiotics, migraine pills, sleep aids, and, best of all, birth control that made me a bona fide, if not full-grown, cyborg.

But, with respect to biocomputation now, it most certainly enhances strictly biological life – but not for everyone. The power of biocomputation, the biological and digital, to enhance human life is held largely for the richest people on the planet – those with access to high-quality health care living in the most developed countries. So, most people on the planet are participants in this development of the digital-biological, dry-wet-dry-wet, as recipients of the negative blowback – the run-off from mineral extraction, war, depletion of environmental stability, etc.

If you are wondering about the age-old fear of humans becoming superannuated by machines or digital automation, this, I believe, is something potentially (in the best-case scenario, which will probably be after my death, if ever) emancipating for humans and our large brains.

We strive on abstraction: humans are at their best when grappling with complex abstraction. If we have machines doing all the simple tasks (even if by means of complex abstraction), humans can be free to discover, create, grapple with, and be humbled by more and new complex abstractions. This is why art is (or could and should be) at the forefront of rapidly changing science and technology.

There are certain kinds of complex abstractions only humans are capable of creating and identifying. Often, this is identified as “art.” Or perhaps I should say only biological beings – vertebrates in particular – are capable of making art. The ornithologist Richard O. Prum has written a brilliant book, Evolution of Beauty, in which he argues for understanding the art-making worlds of animals. And ultimately, the biological brain is not digital, and it is highly improbable that it, or a semblance of it, ever will be made such.

You are also a curator- you have recently put on Gut Instinct: Art, Design, and the Microbiome, an online exhibition about art, the gut-brain axis, and the gastrointestinal microbiome-; As a curator, what would it be your biggest curating extravaganza?

While I love curating, I am not really focused on this part of my kit of tools/talents right now. Ideally, I would love to start a school of ASD, Art-Science-Design, that has a curatorial department/gallery/fund supporting exhibitions like those at the Wellcome Collection and similar to what is going on in connection with the University of the Arts London, Central St. Martins and other branches. I also love the curating at the Beall Center for Art and Technology at the University of California, Irvine.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

The Administrative-Industrial-Complex.

You couldn’t live without…

My husband, my cats and dogs, and books read while on the elliptical at the gym.