Words by Meritxell Rosell

Art produced by the intersection of science, technology and new media arises from philosophical reflections and specific scientific research. But more importantly, the epistemological framework in which lies is vital.

Jens Hauser is an art curator and media studies scholar focusing on the interactions between art and technology. He is one of the brilliant minds that are setting up intellectual horizons for the coming years in this thrilling field. His studies into “biomediality”, a theory developed during his PhD at Ruhr University Bochum, have become a reference to frame these art/science collaborations.

Born in Germany and based between Copenhagen and Paris, he holds a dual post-doctoral research position at both the Department of Arts and Cultural Studies and at the Medical Museion at the University of Copenhagen. He is also a distinguished affiliated faculty member of the Department of Art, Art History and Design at Michigan State University, and an affiliated faculty member at the Department for Image Science at Danube University Krems.

His ability to put together complex and abstract concepts in exquisite and eloquent language makes his work even more valuable.

He has curated exhibitions such as L’Art Biotech (Nantes, 2003), Still, Living (Perth, 2007), sk-interfaces (Liverpool, 2008/Luxembourg, 2009), the Article Biennale (Stavanger, 2008), Transbiotics (Riga 2010), Fingerprints… (Berlin, 2011/Munich/2012) Synth-ethic (Vienna, 2011), Assemble | Standard | Minimal (Berlin, 2015), SO3 (Belfort, 2015) and Wetware (Los Angeles, 2016), and he has also been a jury member for renowned international art awards such as Ars Electronica, Transitio or Vida.

Work like his and other thinkers and curators is extremely important for artistic expressions that are increasingly becoming the voice of the era we are living in.

As a curator, your work lies at the intersection of art and science. What drew you into working in the intersection of them?

I think that my approach is less concerned with the intersection of art and science as such, but more with both my interest in ‘aliveness’, and in the materiality of media – in short: I’m looking at how techno-scientific media materially affect and effectively shape what they pretend to only mediate.

I did my A-Level in Biology and Sports, in Germany, and then was facing a very difficult decision of what to study, hesitating between studying biology – which was the only discipline of the natural sciences I was good at – or media and communication studies, the latter of which I finally chose at this time.

My curatorial work then echoed my own work both in media theory and in media practice, trained by a material approach of German media studies that is very often now associated with what Friedrich Kittler once named ‘the technological a priori.’

And my theoretical interest in media overlapped with my actual media practice, precisely when media art got increasingly obsessed with aliveness. I was working at the time as a journalist, reporter and duty editor for the European television channel ARTE and I was not only covering fields such as contemporary dance, visual arts, opera, architecture etc. but also developments in so-called ‘new media art’.

I began to realize that artists at the beginning of the 1990s had rediscovered the very old fascination with ‘aliveness’ – not only using software and hardware but now also wetware.

My interest in art and science, therefore, unfolds probably more as an interest in the epistemological meaning and the influence of the techno-sciences on our society.

You have co-curated the exhibition Wetware at the Beall Center for Art + Technology. Could you tell us a little bit about the intellectual process behind the exhibition?

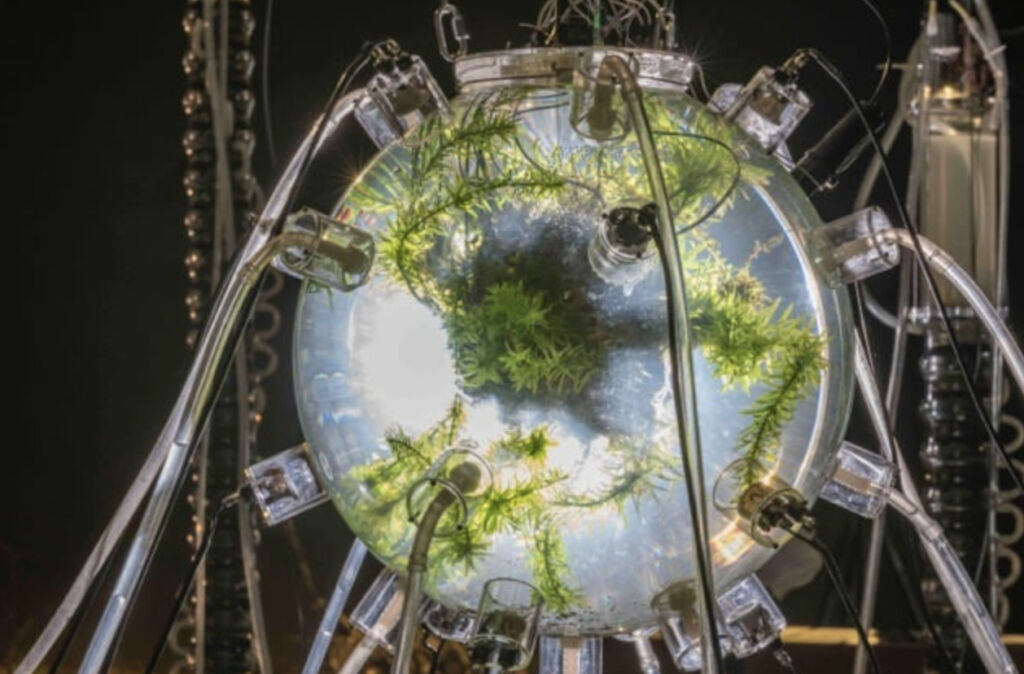

Wetware is an idea that came to my mind when I was helping to set up a show by Paul Vanouse at this art centre in the Los Angeles area some years ago: We discussed what an Artificial Life art exhibition would look like today.

I was at this time also serving on the jury of VIDA, the Artificial Life and Art award by Telefónica, and we witnessed a tendency from so-called ‘dry’ Artificial Life – such as robotics and software-based art – towards forms that I personally have referred to for many years as ‘wetware’ art. The initial purpose was to see how new media became ‘wet’.

Wetware is also a homage to a precursor of philosophical thought in art and technology whom I wanted to acknowledge since he influenced me very much: Jack Burnham.

His work is much neglected in academia, and it’s not very dominant in the media arts either, but his book Beyond Modern Sculpture from 1968 undertakes a biologistic review of 2500 years of cultural history, thinking of art in terms of biological signs. Two years later, he organised the seminal exhibition Software in New York, to which Wetware at the Beall Center now refers back.

The role of scientists has always been to find the answer: why, how, where or when a genetic alteration, for example, happens and leads to develop a disease. But, when in the nineties some artists started to incorporate biotechnology on a material level as a medium they showed that the role of scientific research and techniques could be slightly different and that they can be used to point to other concerns as well. What do you expect from the collaboration between science and art?

When different forms of knowledge collide they produce fruitful misunderstandings. In other words, I think this simplified dichotomy, which is supposedly overcome by trying to add a third culture, is a trap.

Of course, science is defined by its methods and by how to apply these methods, but the methodology that enables scientific research increasingly requires specialised tools, and these tools are indeed shared with other sectors of society.

I suggest that what is shared most between the arts and the sciences are actually media technologies, and we may have to look at the kinds of hybrids that emerge when artists ‘mis’-use such tools.

I think their practices then also have the potential to engage in alternative knowledge production, but in a very different way than in the 1970s when art and science relationships were much more driven by the attempt to formalise knowledge and translate it into aesthetics.

Are these artists making scientific research and its role in society more accessible to the public, or are they changing what society thinks about it?

I think the trend in this area today is the following: Artists may be less obsessed with the question of what we know, but more and more materialise and question how do we know what we know. In other terms, they may offer the possibility of ‘applied STS.’

On the other hand, they demonstrate that techno-scientific hybrids can be democratised and that they can be used to overcome the ideology of hyper-specialisation, which not only leads to accelerated knowledge production in various disciplines but also to contemporary idiocy and autism.

I often see examples of this interesting trend not to necessarily try and make a direct scientific contribution in a collaboration, but to have a more indirect effect on the very questioning of the epistemic objects which shape knowledge.

What would it be your biggest curating extravaganza?

I think that as curators we are first and almost always interested to help artists to develop a very ambitious and thought-through project. From my curatorial perspective, I think what I prolifically and philosophically would be most interested in is contributing to the shifting and explosion of scales:

Going beyond this mesoscopic bubble of the human scale, its limited perceptive apparatus and its very limited phenomenological conception, and instead concentrate the curatorial energy both at the macro and micro level.

Shifting the scales both in terms of time and in physical space from the very small or fast to the very large or slow may lead to extravagant projects other than you might be expecting! Some of my curatorial projects are going in this direction, for example, a retrospective of performer Yann Marussich’s works on ‘immobility’.

Now in May I am introducing a program stream on ‘microperformativity’ – a notion I’m epistemologically working with for some years now – at the Click festival here in Denmark. Another curatorial project I’m currently developing concerns the notion of ‘transplantation’, from the micro to the macro scale.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

I think I may have an allergy to actually hearing the word creativity everywhere: For me, one of the worst enemies is the inflationary talk about ‘creativity’ and ‘innovation’ at every corner, translating into capitalist tools in the service of overproduction of unneeded goods and activities.

Another enemy is of course repetition, for example when one is forced to allegedly gratify narcissistic exposure to play ever and ever the expected role again, instead of progressing with one’s own thinking.

You couldn’t live without…

Well, obviously, as a materialist I would say water, air and carbon. But I am also very much in need of bodily exercises, such as biking and long-distance running. I also would not want to live without sincerity and irony.