Interview by Katažyna Jankovska

What is choreography like when your partner is software? We usually think of moving human bodies when we think of live dance performances. Human actors occupy the centre of the frame, while technologies remain at the periphery of attention. Alexander Whitley, the London-based choreographer and artistic director of Alexander Whitley Dance Company, presents challenges to the conventional approaches to stage performance. By incorporating cutting-edge technologies such as motion capture technology and interactive projections, Alexander’s projects stand in contrast to the traditional human-centred understanding of choreography. Over the years, Alexander has developed an interdisciplinary approach to dance-making, exploring the posthuman condition and posthuman paradigms of dance.

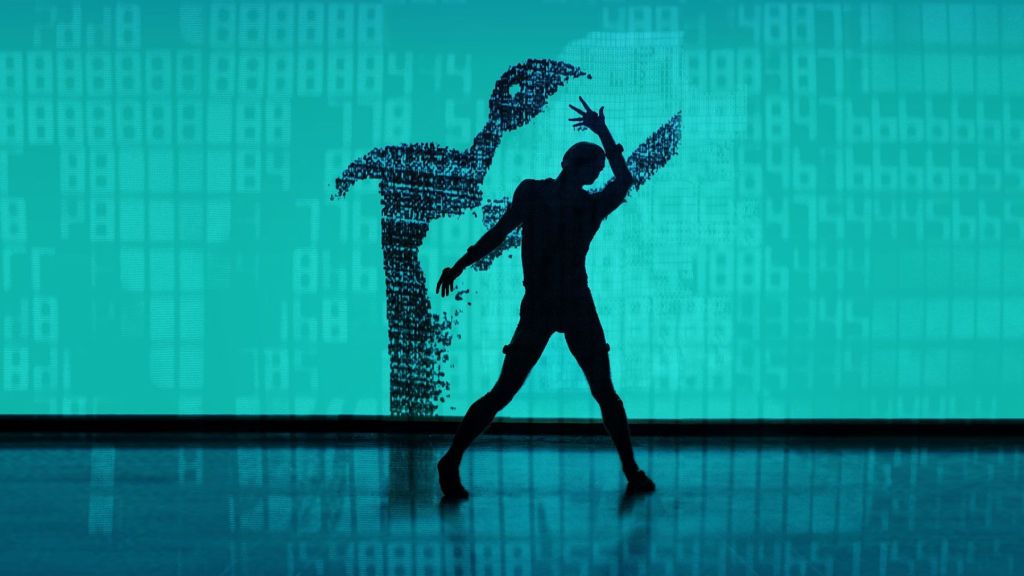

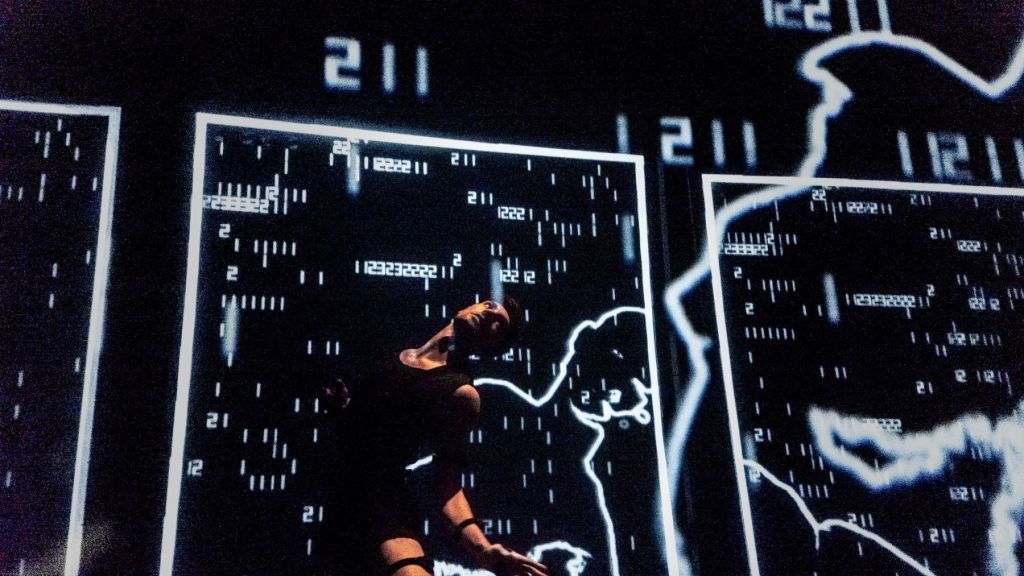

His recent experimental work Anti-Body (recently presented at Sadler’s Wells in London) explores the biological form of the human body through a system of interactive technology. The sensors incorporated in the costumes of the dancers enable the choreography to drive a system of motion-responsive visuals created by Uncharted Limbo Collective and generate real-time projections. The piece is accompanied by an electrifying score composed by 2021 Mercury Prize nominee Hannah Peel and music producer Kincaid.

His previous projects, such as Overflow, commissioned by Sadler’s Wells, incorporates kinetic light sculptures and biometric masks. While this experimental approach requires finding a balance between choreography and visual effects created by digital technology, it also redefines the hierarchy of perceptual importance. Since technology is a performing element playing an equal part in stage performance, Alexander’s projects reject hierarchical ordering and reject the conventional omnipotent role of the choreographer in favour of a more collaborative relationship between different actors involved in developing the work.

Although co-dependency and restrictions assigned by digital technologies impose a certain degree of limitations on the development of choreography, Alexander demonstrates the changing understanding of the role of technology in stage performance and the creative possibilities that emerge from it.

Alexander is also excited by the possibilities afforded by VR. Future Rites is a multi-user virtual reality dance experience that enables the audience to participate in the dance performance and explore the new possibilities of dance creation opened by digital technologies in a unique interpretation of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring. Although integrating technologies into traditional practices often provokes the fear of losing the cherished body in dance performances, Alexander sees it as a complementary element rather than a substitute for traditional dance. It allows him to explore the art form of dance and what it can be. Does dance necessarily have to involve humans in the first place?

For our audience not so familiar with your work, could you describe your current artistic practice?

My background is in ballet originally, but I moved to contemporary dance midway through my performing career. I had an opportunity to work with quite a range of choreographers across a range of dance styles, but my practice really comes to be defined by my interest in technology and the implications for dance and the moving body brought about by developments in digital technology, particularly around motion tracking and interactivity.

Your practice challenges the conventional human-centred understanding of choreography. So far, the role of technology in stage performance has been downplayed; human bodies have been occupying the centre of attention while technologies have been left in the periphery. Could you tell in what way your projects relate to the posthuman paradigm in dance?

There’s a lot to say about that in terms of how bringing technology into the space challenge a lot of conventions. And often people don’t like that (laughs). I think for the dance peers, the first question is why is this type of thing here when dance already does what it does very well. But I am really interested in staging a relationship between human performance and technological artefacts in terms of media that attempts to explore the growing presence of technology in the world and the experiences that are so highly mediated by technology. The holding up of both things in production and building systems that establish feedback loops between them and codependencies between them are all motivated by an interest in trying to better understand and capture the posthuman condition.

It is hard to talk about the themes without also thinking and talking about the practicalities of working with technologies as well because the process is so bound up with these issues of building systems and dealing with failure, noise, information, and patterns in different forms and places. I think my interest in this starts with practical elements of how technology works and what can be achieved through it, but the more I’ve built a practice around it, the more it tends to really embody a lot of those issues I’ve talked about theoretically – the posthuman and transhuman condition.

The use of technology in stage performances challenges, as Christopher Baugh calls it, the “hierarchy of perceptual importance”. Such attempts to unsettle the primary positioning of the human performer were seen as early as the 1920s. Avant-garde performance rejected the conventions of traditional theatre by integrating lighting design elements, costumes designed by Futurists, and responsive stage design. Think about Meyerhold’s kinetic stage design, responding to the movements of the performer. Nowadays, you are using motion capture technologies and interactive projections. How do you approach this distribution of attention between the dancers and technological projections?

It’s a challenging thing to negotiate while working with this technology. I found it useful to talk about choreographing the co-presence of the moving body and other forms of technology because the balance between those two isn’t always equal. I find it important to try and find balance in order to have more control over that distribution. Because a lot of these technologies do overshadow the moving body very easily.

They are designed to produce dazzling effects, which can really drown out the subtleties of what the moving body can communicate. This is probably one of the most significant challenges I face in working with technology and working with collaborators who understand that. Because again, I think the quite important practical element of it is the dependencies that I have as an artist on collaborators – digital artists, developers, and coders who are designing and building these systems but also bringing their artistry to the output. And that their contribution makes up just one part of the bigger system is not always easily understood.

But I found that building collaborative relationships over long periods is essential because there’s so much invested in building up functional and reliable systems from scratch each time, learning how to play the instrument, and composing something interesting with that instrument. So there are many stages to go through, all of which are negotiated between many people. So that all play into what is presented on stage and how these relationships between the various elements work together.

Since you already touched upon the challenges of the working process, could you expand more on how your current working process differs from non-digital technology-based choreographic practice? Are there more dance-led or technology-led decisions?

It’s a very different process. The simplest way of articulating the difference is that, generally, the process of making dance is a very live and active one. Historically, there have been different approaches to it. But the classical approach is around the idea of the choreographer being the knowledge holder who directly tells the dancers what to do, either telling them verbally or demonstrating through a kind of a known language of movement like in a ballet scenario. Whereas in contemporary dance, there are more of a convention around a collaborative relationship between choreographer and dancer, where the material is devised in a range of way, but often, there’s an awful lot of interaction. And a lot of communication goes on at a very subtle and intuitive level.

There are feedback loops between a choreographer suggesting an action or a movement idea and the dancer working with that, suggesting new possibilities that inform the choreographer as to how things can develop. So there’s this very live and fluid process of generating ideas and developing material that technology can bring a hammer blow to and quite powerfully interrupt. So the fluidity and flow that I would say are generally more commonplace in the process of making dance are really heavily interrupted by the presence of technology. I’m speaking specifically about interactive technology. Because without that dependency, there’s not nearly the same kind of potential disruption. But in Anti-Body, for example, where we are using live motion tracking and all the visuals that are seen in the performance, there are huge dependencies between how the dancer moves, how the visuals are responding, and then what the overall effect is. So the process becomes very slow, spread out, to the point that all the elements can work together fluidly enough to have that kind of working process that you would have at the beginning of a normal dance-making process.

And answering your question about whether it’s the dance informing technology or the technology informing of the dance, it’s both. And again, it varies an awful lot. In Anti-Body, some sections are mostly led by the choreography, knowing that the interaction or the way the visuals respond to the movement is relatively loose. Really just providing a kind of background texture to the choreography because we have the projections in front and behind. But then there are other sections where the dancers are improvising and responding to the visuals that are being generated from their movement so that there’s a loose, improvised framework that they’re working around. For me, that is a really exciting and interesting space in working with this technology as it brings about performative situations that wouldn’t be possible in any other way. The interaction is really the primary element of what’s being performed, rather than just the staging of preplanned scenarios.

Over the years, we’ve refined our working process to deliberately allow for long development timelines. We can begin to understand the kind of technology we’re working with and the practical capabilities and constraints around that. And the creative possibilities that emerge from it. And, because nothing is off the shelf, it’s not as though there’s a technology that we know will do exactly this, or we think of a preexisting visual world. It’s the building up of a choreographic and visual language at the same time so that the theme, the inspiration, and the conceptual motivation behind the work are being expressed across many levels – through the music, the visuals, and the choreography. And the enjoyable part of making work in this way for me is that I get to see how other art forms can address or represent a theme that I can explore in one way through choreography. And I think that’s why I’m interested in this kind of multimedia space – I can get further down this kind of explorative lines around a concept than I can by working with dance on its own.

There is a debate on the restriction and liberation that technologies bring. On one hand, when choreography is determined by software, it reduces the body’s capacity to move. For instance, some technologies cannot record movement in the vertical direction. On the other hand, there are always limitations such as stage, costumes, etc., and what is more important, it’s again a very human-centred perspective. What are your thoughts on that?

Having worked with interactive technology and stage productions in the past, we attempted to try not to succumb to what I perceive to be its limitations of it. But we ended up just failing to do a lot of what we were setting out to do because we were resisting too much the constraints that the technology was bringing. So in Anti-Body, I consciously chose to accept those limitations and constraints and try to work around them by pulling them in and putting them in. And I think a traditional dance audience would look at this thinking, “Why are you not doing a lot of what you could or should do with dance? Because of the presence of all of this technology?” but for me, it points in a different direction and suggests these different possibilities that de-centre the deep prior to the significance of the human actor as the sole subject.

I think that’s such a hugely important part of working with technology – really understanding and getting to grips with the constraints it brings. So often, people are motivated to work with it because of the possibilities they see, and then they just come up against these massive barriers to actually achieving those possibilities by the many technical hurdles they have to overcome, especially when working in the subsidized art sector. Anti-Body took my choreography and my thinking about choreography to a different place; as a result of not having a lot of the options I would normally draw upon, it didn’t allow me to fall back on a lot of the habits that I would narrowly workaround.

This willing attitude towards technology’s constraints is really important. At first, I was drawn to the spectacular element of working with technology. It seduces you because of the spectacle that it produces, which has always been a part of the performance. And like you say, the costume design in a more conventional theatre would be a part of that. I performed in ballets where I was wearing ridiculous layers of costumes that were ornate in their beautiful materials but made it really hard to move in them.

Because you’re swamped in material or wearing shoes that make it difficult for you to perform what you’ve been rehearsing in the studio. But it’s all because ballet traditionally had a priority to hold up to the world an image of wealth and privilege to the wealthy, privileged people sitting in the theatre watching it. So I think the same things apply, but they’re often not seen in that way because one is in the context of a long-established vision. And the other is in the context of innovation. And those conservative voices who would tend to prioritize the traditional can’t see this. It’s exactly the same thing but in a different image.

In your work, The Age of Spiritual Machines, inspired by today’s technologies, your dancers embody principles of machine intelligence. As you state, “their movements and relationship to each other are informed by the way technology, rather than the human gaze, sees the world”. It made me think about Futurists, who, inspired by the technologies of that time, created mechanised movements associated with the dynamic energy of technology. Seems that dance keeps reflecting changes in society. Can you elaborate on what principles this work is based on?

There are similar themes to Anti-Body. It was created around the same time but in a slightly different context. We chose not to bring any technology into that piece. There’s a kind of robotic style of movement popularized through hip-hop culture that is literally a mirroring of a quality of technology or a characteristic of technology that emerged in the world, and then that was brought into the body.

I’m really interested in how we create technology in our image to some extent, but also, it acts as a mirror for us to both reveal features of ourselves and principles of the technology we create to describe ourselves. There’s so much talk nowadays to describe the human body and psychology in terms of the hardwiring of the brain, the kind of talking about hardware and software to describe human processes.

I’ve recently been particularly interested in how artificial intelligence and computer vision work to map, read, and understand the body. Many developments in motion tracking are around the marvellous tracking systems where a camera can see a human body move and then imprint onto it a basic skeleton shape. So the idea is to work with the concept of how technology looks upon the body and how it breaks it down into constituent parts and reduces the body to the skeletal system. So it’s really looking at the body as a skeleton. In making that piece, we were thinking about how we could start devising material from the first principles of those systems – how the skeletal system move, how the respiratory system functions or the circulatory system works.

But we’ve also looked a lot at the new kind of imagery that artificial intelligence is now generating and the morphing transitions between images. So we explored how we could try and derive that quality from the kind of imagery that this technology is producing and bring that into the body in a way that in other productions in the past, for example, we’ve attempted to recreate the quality of time-lapse footage by speeding movement up very quickly. I’m interested in not only the functional underpinnings of these technologies but the effective output they produce. How the qualities of media that different technologies produce can then can be incorporated into the body and worked with as a way of trying to capture the effect of these technologies that are so increasingly commonplace and bring that into the body and put it onto the stage.

Your choreography has also been re-materialised online. In Future Rites, you are extending corporeality into the virtual dimension. Technology integration into dance is sometimes associated with the fear of losing the essence of dance – moving physical bodies. As DeSpain asks – does dance have to involve humans? How much is it about the abstract qualities of movement (direction, shape, speed, complexity…)?

There’s a huge amount of fear in making this kind of work. And for understandable reasons. The cherished body is disappearing. Life performance is an amazingly powerful thing and should always be cherished for what it is. When you start talking about the idea of having remote virtual performance experiences where you can’t perceive all of the presence of the performer behind the characters you are encountering, people think, why are you taking this away? And I find myself talking a lot about trying to convince people of the complementary difference between these kinds of performance platforms or contexts and experiences rather than them being competitive alternatives.

There is a progressive move to try and bring as much of this as possible into virtual spaces. But for me, it seems slightly absurd – to create a metaverse and effectively simulate the whole world in a virtual space. Why do we want to recreate the world exactly as it exists rather than thinking about the different kinds of worlds and experiences that we can create and how they can complement what we have in the real world? So going back to these questions of the recreating of the real in virtual spaces, I am personally a lot more interested in exploring the alternative forms and abstract ways of representing the moving body than I am in attempting to really faithfully reproduce or recreate the look and feel of the moving body. Partly because of the tendency for our attempts to do so, even with the billions of dollars that are being thrown behind by big tech companies in Hollywood studios. But also because I don’t have the money that they do to do that. So it’s much easier to accept again the limitations of our ability to simulate and recreate the look and feel of a move and body and instead abstract it and explore.

The process of abstracting reveals the structure of our psychology and our tendencies to look for the human form. That, again, is a sort of deep fascination for me in terms of how augmenting and reshaping the form of the moving body can explore what that threshold is and how it then opens up an understanding of movement into a broader domain of thinking. It thinks about choreography much more broadly than just about the movement of the human body. And because choreography can exist in any kind of moving form, we obviously tend to think about it primarily through the form of the human body because that’s the one we can control most directly. But now that we can simulate and generate all sorts of different shapes and forms, choreography can be thought about much more broadly. I find that exciting, not just because it expands my practice field but also invites people from other disciplines into the space of choreographic thinking.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

Absurdly, I would say technology. Because of how it is generally designed to distract people, not to enable them, I find myself slightly entrapped and, a lot of the time, distracted from the things I should be doing and want to do.

You couldn’t live without…

My dance practice and all that dance brought me through my life – I think I couldn’t live without that. Being without that in any way would fundamentally change who I am and how I live.