Interview by Daniel Mackenzie

The world’s largest and most prominent particle physics research centre sits just outside Geneva and made the headlines in 2012 with the discovery of the Higgs boson, also known as the God particle.

It is home to the Large Hadron Collider, the highest energy particle accelerator in existence, and, if that wasn’t enough, the biggest machine human beings have ever constructed. Its primary structure is built into a 27km ring that sits 175 metres below the earth’s surface.

The significance of this site in the global scientific community goes without saying. To those who believe that investigations on a quantum level could reveal truths about our basic physical make -up, consciousness and what existence actually is, the significance is equally powerful.

Only this year a group of pilgrims from the UK visited the site on an unofficial mission, drawn by an exploratory affinity and propelled by dealings in magic and a desire to understand the composition of reality.

If science is the practical and magic is spiritual; one might ponder on art as the soul, a means to transmute and disseminate the findings of any esoteric or obscure process. Always entangled but ever lessening the rift that separates them, some practitioners have equal footing on either side. In 2009, one year after the LHC was first switched on, the CERN artistic programme was established by Ariane Koek.

Arts at CERN aims to establish and explore a dialogue between creatives and physicists via numerous channels – exhibitions and studies, music and new media. A diverse group of organisations help to implement the programme, including Liverpool’s FACT (Foundation for Art and Creative Technology), Barcelona’s CCCB (Centre de Cultura Contemporània), iMAL (Interactive Media Arts Laboratory) based in Brussels and various Swiss partners.

This cross-European collaboration is truly a testament to what can be achieved when this wonderful continent recognises the strength and joys of working together. Koek’s history working in the arts has an international reach even wider in scope.

She has established, directed and advised in a broad range of projects which gravitate largely towards science but tread into other disciplines too. She has previously been an award-winning producer for the BBC and won the Clore Fellowship award during her time as director of the Arvon Foundation for Creative Writing.

Back to CERN and science, Koek devised the three primary strands of the arts wing: Collide Residencies, Accelerate Research and the Guest Artist programme. Through these, the research facility has been able to inspire artists who, in turn, share their impressions with the world, transforming into different dimensions and constructions.

Koek’s new book Entangle: Physics and the Artistic Imagination is a counterpart to an exhibition she curated, Bildmuseet in Umea, Sweden, from November 2018 to April 2019. As the title suggests, this continues the straddling of worlds central to Arts at CERN and Koek’s core work: curiosity and investigation, creativity and expression.

Right: International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation Configurations 5, Goshka Macuga

Can you explain how your formative experiences lead to your work in arts, science and with cultural organisations?

I always say that I have always followed my heart – what intrigues, inspires, and triggers my imagination. The sources of this (heart) response are ideas, people, places and culture.

So everything I have done has been part of this and led to my work in arts and science as well as with diverse cultural organisations. There’s been no plan – just instinct and passion for new ground-breaking ideas and knowledge-making which breakdown silos.

Maybe my earliest experiences of being born in the USA, being flown out at 6 weeks old to live in Dacca, Bangladesh, living there until I was two, then moving back to the USA via Venice in Italy and then on to the UK have led to my approach to life and love of transdisciplinary working across boundaries?

Plus having two parents with very different backgrounds – one American-Dutch from New York and the other English. Who knows? Certainly, my MA thesis on Mary and Percy Shelley, focussing on Frankenstein, inspired my love of boundary-breaking creativity as well as arts, science and my passion for the history of ideas.

This tiny novella is so rich and complex. It is packed full of surprises – such as hidden messages and clues to her relationship with Shelley and her anxiety over authorship. Frankenstein translated means Marked Stones – so, for example, Mary in effect is hiding her own initials in the name of the creator of the monster. There is also just the sheer imagination of this 17-year-old girl who created science fiction with her investigation of galvanism as well as the philosophy of the era through writing this amazing story.

Just extraordinary. For me, this is what matters: new ideas, new knowledge and engaging with them in surprising, critical and creative ways. Mary Shelley does this in Frankenstein so brilliantly – and beat the much more celebrated men in their story-telling competition that storm-ridden night by the shores of Lake Leman outside Geneva.

At the end of the day – it is the passion for new ideas, creativity and new ways of looking at the world which drive the work I do. I seek to do this in organisations and cultural institutions which have new knowledge and its transmission at the centre of their missions. Having worked in big public institutions as well as now independently, means I know how to work inside big bureaucracies and cut through the tape, as well as how to work outside with and for them.

Your work and expertise are incredibly diverse. Would you say there is a central thread that runs through and connects it together?

Definitely and defiantly the imagination is the answer to this! The imagination is the thread that runs through everything and connects all my work and experience. It links with my love and belief in the power of ideas and new knowledge to change the world as well as the individual Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is all about the power of the imagination, the BBC was a place when I was a staff producer/director there in radio and television in the 90s and the 2000s, where we could be imaginative and show daring.

The Arvon Foundation for Creative Writing, which I directed, is an organisation dedicated to making the power of the imagination and words open to all, and CERN is an institution which is dedicated to pushing the frontiers of fundamental knowledge and the known world. You can see the link!

My work today continues that very strong thread – we might even call it a steel-silk cable, not thread, which is both fluid, delicate and strong! There is another thread too in all my work – never belie,ving that anything is impossible. Without that belief, Arts at Cern would have never happened. So many hurdles were thrown in my way. But I ploughed on.

There are many other examples in life. Like at the BBC, I was told Anthony Minghella would never do a new commission for a radio play inspired by Samuel Beckett, but I ignored this advice and Eyes Down Looking, which I produced and which he directed and was his last radio play, was the result. Everything is possible, and there is a solution for everything – if you show commitment, passion and determination!

How would you describe the current and increasingly complex relationships that connect art, science and technology?

It is a very dynamic field at the moment which is constantly developing and shape-shifting. As science creates the knowledge from which technology is made and applied in the world, the arts are becoming increasingly entangled with it in many different ways.

The arts are now even more than ever THE vital part of the social, psychological and cultural analysis of the vast and rapid developments in science and technology.

The arts are our cultural conscience – increasingly more so than politicians and politics. Look at the way, for example, Extinction Rebellion and Culture Declares an Emergency is leading the way in showing how the arts and artists can make a difference and take the lead in the good for all.

There is a massive sea change – which is taking us very close to Percy Shelley’s belief that the imagination is a force for moral good and revolutionary change, expressed in his Defence of Poetry.

In times of climate crisis, complicated relationships with technology and political strain, what role does art play today in describing contemporary society?

The Arts are not just a describer of contemporary society and nor is it simply the so-called ‘canary in the coalmine’ as it is commonly called. The arts also play the role of the rebel, the inquisitor, the liberator of the unthought-of and unspoken, the innovator, the agitator, the inspirer, the reflector, the voice, innovator, the maker, the way of taking us beyond ourselves and our world, a form of transcendence, a space for epiphanies. All these diverse roles are essential to our culture, and all are equally valid and important.

However, with the current state of politics, there is also a drive towards the arts becoming much more solution-based and awareness-raising based because the climate crisis is accelerating, and our politicians are failing to take the big action needed. The arts are now the place to think through the crisis and how to carry out the action for the good of all, including the planet.

In addition, out of necessity because of the climate crisis, the arts are also becoming more design-focused – a place for coming up with solutions for the global challenges we are facing – and the line between the arts and design is becoming increasingly blurred.

There is an inherent danger here. I really hope we don’t stop valuing the transcendent and the poetic, which offer us unexpected insights and experiences of our universe that we have not dreamt of and which are not just fixed to solving, expressing or raising awareness of important social, environmental and political problems.

What drove the initiation of an artistic programme at CERN? Are there any specific intentions related to the programme?

That seems a simple question but it has many layers! I approached CERN in 2009 and said “Why don’t you do an organised arts programme? I will come to you for 3 months and do a feasibility study with you for free to see if this could be set up.” They hadn’t thought of doing their own programme before and said yes.

I had just won a Clore Fellowship – an international leadership award – which gave me a small stipend and the time and space to explore culture, think about leadership and reassess my ways of working, including encouraging me to go on attachments as part of the scheme.

So I went to live, work and learn about CERN for 3 months without them needing to pay a penny to see what could possibly happen there.

The inspiration for the programme I devised and then directed there for its first five years was partly influenced by the way in which the Clore Fellowship had personally given me the time and space to encounter and challenge my work in culture.

I thought, what if that was applied also to artists, and they were given the time and space to go into the unknown (physics!) with no pressure, with all their expenses covered, to refresh and renew their practice at one of the epicentres for new knowledge, cutting edge engineering and technology?

What magic could happen then! I was also partly driven by my wish also for scientists to have the opportunity to encounter new ideas and ways of looking at the world as well and for that to feed into their often hermetically sealed culture too.

Another driver was to break down the CP Snow dogma of the Two Cultures by putting the arts and science on the same level. Obviously one key way to do this is to address the economics. The economics of science are totally in a different league from the arts and artists.

So again, right from the first design and subsequent implantation of the Arts at CERN programme, I fundraised for the artists to have a monthly stipend/salary, plus their lodgings, subsistence and travel all covered, so that they weren’t second-class citizens from the arts scrabbling around for their own funding on the Collide residency strand.

Instead, the artists were well-funded and genuinely given the chance to research, discover, and get lost, with a well-defined programme which also explicitly at that time expected no outcome from them: only their own fundamental research in one of the temples to fundamental research, as well as participation, public lectures with their scientific inspiration partner and a willingness to engage with the extraordinary minds at CERN.

This mission to ensure artists are well paid on residency programmes for sharing their knowledge and expertise I have taken through to other residency programmes, including the Earth Water Sky environmental arts and science residency, which I created for Science Gallery Venice in Italy.

It should also be said I was incredibly lucky that when I approached CERN with my idea of creating an international world-class arts programme of the highest quality to match their science – which became enshrined in their first cultural policy, Great Arts for Great Science – that the then newly appointed Director-General Rolf-Dieter Heuer and his Director of Communications, James Gillies, were looking for new ways of opening CERN up further to society and showing the inspiration of CERN science on society.

This was a pure coincidence. So serendipity played a part in the alignment of my vision with theirs at the time. I presented my design and feasibility study for the Arts at CERN programme in 2009, and the CERN directorate unanimously voted for it and said there are two catches.

One, we won’t pay a penny for the programme except for the salary of the person who runs it will be paid by the Director General. Out of his special budget, we will pay the salary of the person who runs it and two we want you to do it. When can you start?

So that’s how I had the great honour to be allowed to create, implement and direct my vision for 5 years, which I joyfully did until the end of 2014. I am delighted and happy to see it thriving to this day!

Would you say that the insight that comes from connecting artists to CERN feeds back into the centre, expanding its potential as a way of understanding ourselves and our reality?

Absolutely. Some of the scientists who work or encounter the artists on the Arts at CERN programme say that these encounters bring new ways of looking at their scientific work – new directions and new ways of thinking. Others say that it refreshes their work in a more general way because they find it stimulating to encounter another aspect of themselves and be more put in touch with their humanity by working with the artists.

I remember when I hung the Antony Gormley sculpture up at CERN which he had donated after a visit there, a crowd of physicists gathered around at the bottom of the stairs and said how grateful they were that art was coming into the walls of CERN because they felt cut off from the rest of the world. Science can be very monastic – and these physicists were expressing this directly.

After all, the arts touch our hearts, minds, souls, and senses as a way of understanding ourselves and our reality. Science is another way that

humans have developed to do this. Together with sciences, the arts are our fundamental ways of knowing ourselves and our universe and our place in it. Put the two together, and you vastly expanded the field of knowing ourselves and our reality.

So yes, it all does feedback into this extraordinary laboratory with its many experiments – over 80 – which investigate reality. However, it is currently impossible to prove if such encounters lead directly to new discoveries or ways of problem-solving in science. But it does also affect the organisation as a whole which is provable.

There were spin-off influences from establishing the Arts at CERN programme. Ideas Square – CERNis innovation unit which brings people from different disciplines to innovate and come up with solutions to global challenges – was inspired by Arts at CERN, and CIneGlobe, the CERN homegrown Science Film Festival really expanded its ambition from a small internal festival to an international one by following the Arts at CERN.

All this ultimately feeds into CERN – the well-being of the scientists with new outlets of expression as well as the profile of the organisation itself. This shows the cultural and organisational change which can happen due to the influence of the arts.

You have just published a book, Entangle Physics and the Artistic Imagination, where you closely examine the influence of physics on today’s art, design, and architecture. What drove you to write the book? And what was the most surprising or satisfying finding after finishing it?

Also, when I was at CERN, I was far too busy making the programme happen, including fundraising, marketing, publicising and running it, to even write a book about it or document it. So I didn’t want to make that mistake again. So when, one of the world’s most beautiful galleries – Bildmuseet, in Umea, Sweden invited me to do the exhibition in acknowledgement of my work in the contemporary arts and physics field.

I wanted to document I had to make sure that people who could not make it to the exhibition could have a sense of what we did there and why. Katarina Pierre, the Director of Bildmuseet, generously gave me this opportunity as well as the 3 floors of their stunning museum with their amazing technicians to curate the exhibition, which has the same name as the book.

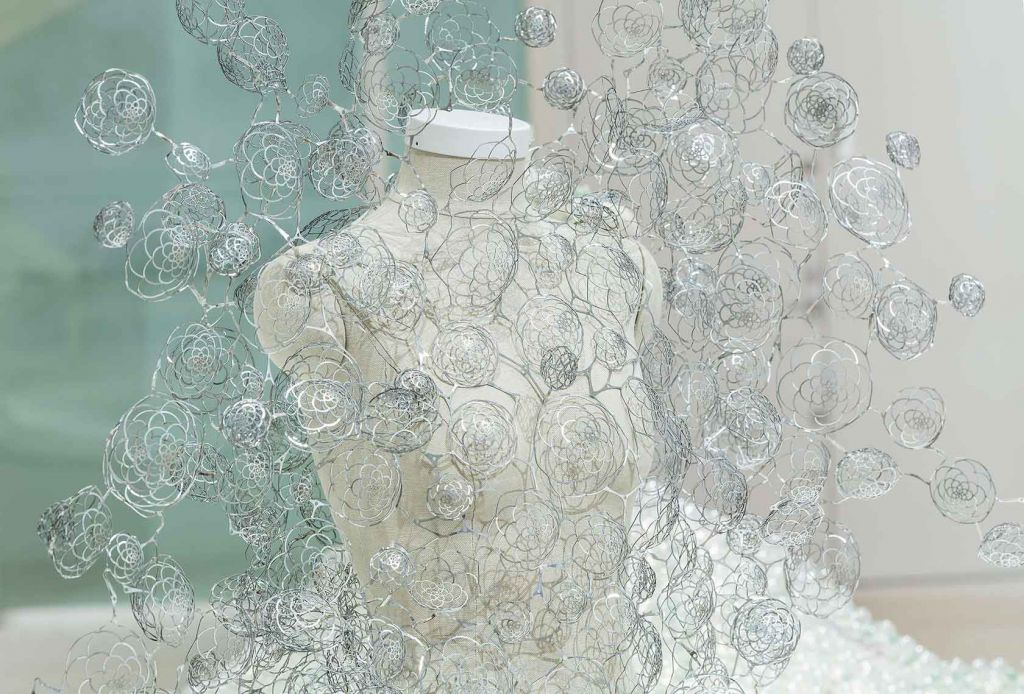

It featured artists such as William Kentridge, fantastical dresses made out of glass balls and laser-cut silvered leather by the fashion designer Iris van Herpen, installations by Ryoji Ikeda and the architect Sou Fujimoto and much, much more – including an extraordinary work called Singularity by the youngest artist in the show, Solveig Settemsdal who had just graduated from the Slade School in London.

There were 14 international leading artists in the show in total – 4 of whom I worked with on the Arts at CERN programme, including the first and third Collide artists in residence, Julius von Bismarck and Ryoji Ikeda and Visiting Guest Artists Goshka Macuga and Iris van Herpen. Every one of the 14 artists in the show in different ways draw on physics in the practice of their work. Their work clearly showed the influence of physics. But this is only the beginning.

The most surprising or satisfying thing after it was finished? Just how great the publishers Hatje Cantz were to work with and the delight of reading Philip Ball’s great essay on the role of the imagination in particle physics. A deeply respected and authoritative science writer, Philip is always ahead of the curve, and this essay marks a sea change in science by being an open acknowledgement of the role the imagination plays in science.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

I actually created the Arts at Cern programme in order to combat the chief enemy of creativity: the production line attitude to creativity with fixed deadlines, fixed outcomes, and fixed expectations before one has even begun the creative process. This turns creativity into a product and production line – a ticking box exercise.

There are other big enemies to creativity too. We are in a quick-fix culture in which people are scared of getting bored, getting lost or being out of your depth. Without getting bored and being prepared to go into areas you know nothing about, creativity also dies. This needs courage, energy, and commitment.

Combine that with culture and some individuals’ lack of curiosity and lack of the wish to be challenged to the very core of our being, and then you get a creative desert.

For me, the essence of creativity is to go beyond the known – into the unknown and further still…and further still. To push, to dream, to risk, to fail, to be committed. You have to be fearless to do this and take risks.

You couldn’t live without…

Light, creativity, the sea, physics, trees, the imagination, Nature, friends, books, oxygen, ideas, love, hope… and the magic of Iris van Herpen – someone who puts the imagination and their work, exploration and discovery first before ego.