Interview by Christopher Michael

Despite having lived in Europe for over a decade, Berto Herrera’s work finds its roots within a particularly American anxiety. Herrera’s practice is largely interested in the types of surveillance and censorship which have become synonymous with the US in recent decades. Coming of age and making art in the era of the Patriot Act, where the American surveillance state has grown stronger and more prominent, Herrera’s work has often sought to unveil the relationships between the watcher and the watched.

Having grown up in an American military household and later serving in the military himself, Herrera has a unique perspective on these issues. This is evident in the militarised aesthetic in his latest solo show, Call Me Collateral Damage, at Ghost Gallery in Los Angeles. Throughout the exhibition, imagery of military and surveillance apparatuses form the basis of the work, from used shooting targets resting on cinder blocks to self-portraits of the artist donned in camouflage. For American viewers, these signifiers feel eerily familiar, and Herrera argues that this type of imagery forms (s) the core of the American visual language.

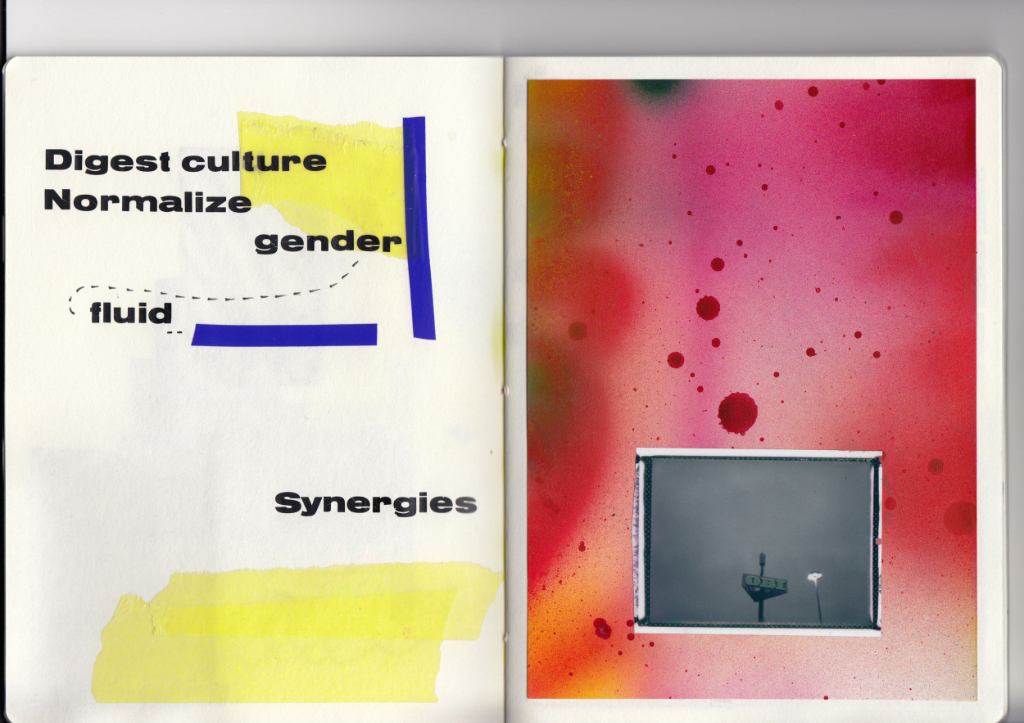

Herrera finds many parallels between these modes of surveillance and the current state of digital culture and social media. This is apparent in the series of untitled collages that make up most of the show, which feature a dizzying blend of images: conspiracy theorists, cult leaders, iconic cartoons, brand logos, military aircraft, and surveillance equipment. Viewing the collages is akin to scrolling through social media, where cruelty and cuteness live next to each other under the surveilling eye of platform capitalism. These works mimic the information overload, which keeps viewers in a frenzied state, allowing us to forget that we are being watched.

Much of this practice is also informed by Herrera’s work in the corporate world, having served as art director and creative consultant for brands like Famous Stars and, Straps and Adidas. Working in these capacities, Herrera has often reflected on the role branding plays in the world of corporate marketing and how we create our identities in the digital era. His work plays with graphic design tools as a critique of how we seek to sell ourselves to others. As he writes in his artist statement/personal manifesto: We aim to brand everything and everyone into digestible concepts, even if those concepts aren’t meant to be digestible.

While Herrera may find influence in contemporary American consciousness, the themes of his practice speak to global anxieties of the current moment. Considering the outside power social media platforms like Meta and Google have on a global scale, we are all increasingly at the mercy of their modes of censorship and surveillance. At the core of his work are questions about how we are supposed to live in a world that increasingly sees our identities merely as points of data. Alluding to a line in Wanda Coleman’s poem, ‘Notes on a Cultural Terrorist 2’, Herrera observes that we are all collateral damage to everything happening right now.

Your practice focuses particularly on surveillance and censorship, especially as they relate to building one’s identity or ‘branding.’ Where does your interest in these entanglements come from?

These concepts have always been present, albeit veiled in my own eyes. However, they only became prominent once I started working in fields such as art direction, creative direction, and corporate constructs. In these environments, my work shifted towards these topics. Reading various books and working in these fields gave me the tools to analyse and articulate my focus.

These experiences shaped my worldview and took on aesthetics, culminating in a singular point. These topics surround us every second of our lives and are very abstract in many ways. I aim to turn the gaze of all marginalised peoples toward the watcher, using the tools taught by the watchers as a weapon against them.

Much of your recent work incorporates a militarised aesthetic — from photos with ghillie suits to digitised challenge coins to shooting targets incorporated into sculptural work. What draws you towards such aesthetics?

These aesthetics are a part of my visual language. I come from a military household where these visual cues always surrounded me. In my childhood, I would play on military bases where MPs (Military Police) were ever-present and watching, along with higher-ranking members on base. I remember playing with cards that had an array of tanks and their specifications on them and seeing my father iron his uniforms and place military regalia on them for special events. These visual cues from my childhood are integral to my language. They form the core of the American visual language.

You recently had a multimedia solo show, Call Me Collateral Damage, at Ghost Gallery Los Angeles. You have noted elsewhere that the title comes from Wanda Coleman’s poem ‘Notes on a Cultural Terrorist 2’. Could you tell us more broadly about the influence of this poem on the work and the exhibition’s themes?

First, Wanda Coleman’s work is profound and strikes me deeply, as it should strike others. She is the voice of the disenfranchised and working class in America. When I read her poem Notes on a Cultural Terrorist 2, it hit me deeply. Though written in the aftermath of the Watts Riots, it feels very relevant today, given the global political, social, and cultural divides that create high tensions. With the advent of social media, we can’t escape this dread. When I read the line, “Call me collateral damage,” I stopped and stared out my window, focusing solely on that. Funny enough, I didn’t finish the poem until later; that line had me in a chokehold, and it’s what everyone feels right now. We all are collateral damage to all the things happening right now.

The themes of surveillance democracy, post-identity, censorship, and de-branding share much in common with your recent digital exhibition space, Proxy Judicator, created as part of Six Minutes Past Nine’s Hybrid Realities: Lab program. What was the difference between working through these ideas in the physical space of Ghost Gallery and the digital space?

Space, whether infinite or finite, is nothing but a blank canvas on which narratives and emotions can be conveyed and retained through the transmutation of that space at the will of the creator. I approached both with that ideology in mind. In the physical manifestation of the show Call Me Collateral Damage, I am bound by physics, time, and resources. Within that Venn diagram, I aimed to convey a mood and feeling of dread and information overload, much like how we ingest vast amounts of information daily. The collage pieces are arranged to resemble browser tabs, like on an iPhone with 452 tabs open, while the paintings invite you into the space, making you feel more overwhelmed the further you go. Ultimately, you are confronted with the death of the self, as we all are.

My space in Proxy Judicator was built to convey a mood and emotion. The environment I created isn’t inviting; once you step outside the safety of the surveillance office, you are greeted with an oppressive feeling, with drones flying around and the all-seeing gaze above, larger than life. It’s also meant as a point of discovery; if you avert your gaze to the watery floor, your only safety is downward until you reach landing pads and pavilions. All spaces, even my social spaces, to some degree, are meant to convey a feeling.

Call Me Collateral Damage was also a return to LA after living overseas for quite some time (2006 at Han Cholo Store/Gallery). What was the experience of being back in the city like after having been away?

Between my first solo exhibition in LA and my latest solo exhibition, it has been surreal for me. I have returned to LA for work, family, and personal reasons. Since I’m not a native of this city, I tend to have a love/hate relationship with it, which is valid for many people in different places.

Although I am a U.S. citizen, I have lived away from the nation for nearly a decade. In many ways, I don’t feel “American” anymore when I am in my homeland, nor do I feel German, as I am seen as an “ausländer” (outsider). I feel I am on a broader concept of being European, whatever that means.

I feel I don’t have a home in many respects, given my upbringing in a military household and frequent moves. Home isn’t related to a place but more to a nucleus of ideas and people, near and far. It feels strange to be back, knowing and seeing so much has changed post-COVID and post-George Floyd. Nonetheless, it’s still very exciting to be back and share what I’ve been cultivating over the past decade. Much like James Baldwin, being away has given me clarity about the U.S. Also, some sunshine never killed anyone.

Solitude or loneliness: how do you spend your time alone?

Solitude—I believe we as a species are inherently lonely. Just look at all we have built to gain connection to others (eyes on you, social media and AI). People must seek out solitude; when they find it, they must be comfortable with their thoughts. I usually spend my time alone reading, thinking, or being in the moment’s stillness.

One for the road… What are you unafraid of?

Failure.