Interview by Nathalia Dutra Maciel

Cammack Lindsey is a Berlin-based artist who combines complex oppression networks to embody collective resistance by investigating scientific and historical relics of failures from extractive capitalism. Their work exists and is influenced by the transition period of opera into musical theatre. From that intersectional place of existence, they bring holobotical musicals that emerge from symbiotic interactions between the (non-human) subvisible world and the human—Cammack centres within their theory and practice a desire to expand and redistribute space. This intent is often explored through collaboration with cyanobacteria, micro-algae, code, the voice, sound and the materialization of colours, magic, ghosts and clouds. Through these profoundly multifaceted performances and installations, Cammack honours possible stolen futures.

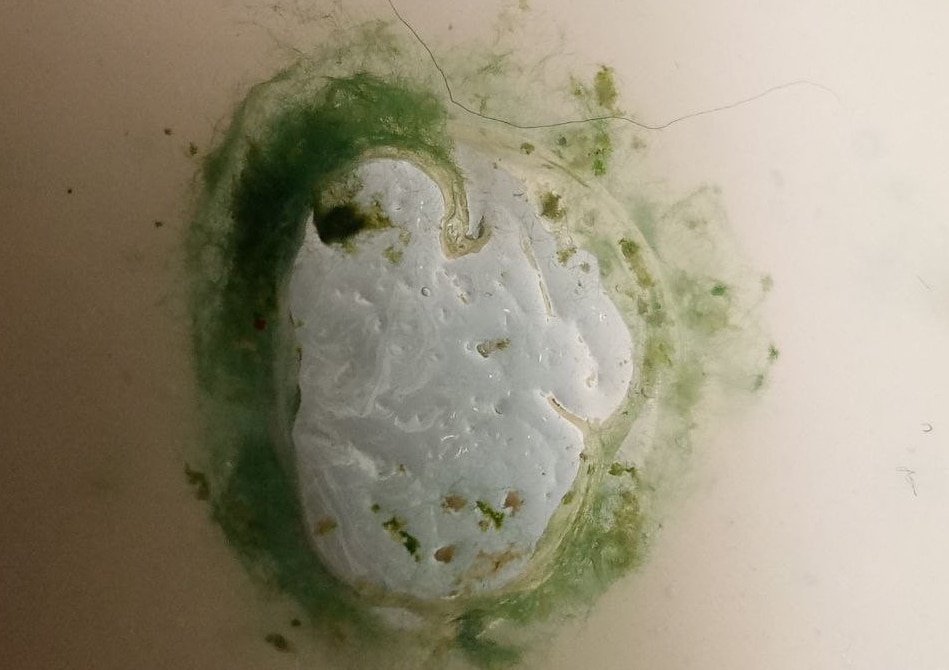

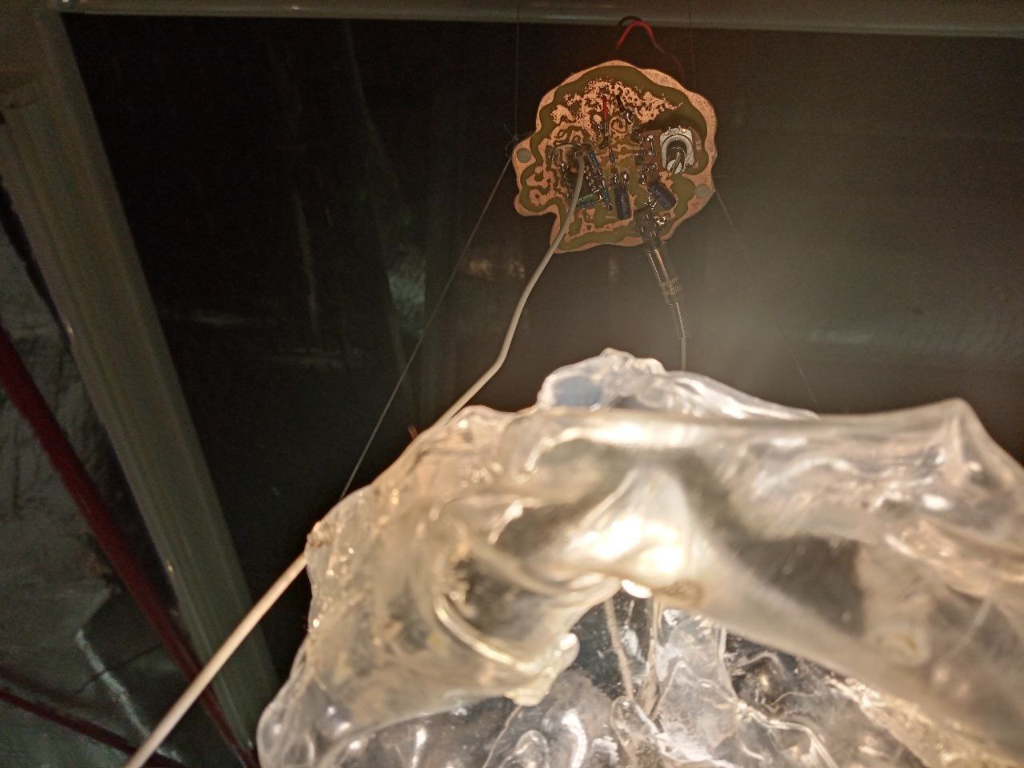

Their work Holobiont: Relics from the Revolution is showing at the group exhibition Hackers, Makers, Thinkers at Art Laboratory Berlin. Holobiont: Relics from the Revolution is a science-fiction musical installation that grew from imaginary foundations and was set inside a factory where toxins from cyanobacteria are extracted to transform into profitable products. By creating imaginary lines, Cammack forms an environment of symbiosis between an intersectional working class and toxic cyanobacteria amid revolution. During the context exhibition, they presented excerpts of their newest musical theatre piece currently in development, Cyanotoxic Romance, which exists as a continuation of Holobiont: Relics from the Revolution, that revolves around love and relationships between multi-species in times of precarity.

About 2.5 billion years ago, the cyanobacteria’ reproduction led to a sudden increase in oxygen levels. This caused fundamental change on Earth and established the basis for life as we understand it today. Cammack’s work invites you to envision how cyanobacteria and humans could symbiotically expand through music. It navigates musical pathways for algorithmic computer music and natural patterns from cyanobacteria subvisible world data and finds a shared narrative through interdisciplinary investigation. Developed through histories, personal and collective, this work exists within a proletarian queer-feminist thought framework and urges for alternatively prolific closeness and intimacy between humans and nature.

I would love to start by getting your definitions of the “the human” and the “non-human subvisible world.”?

The human and non-human subvisible worlds are different elements in one realm, perhaps, in that one without the other wouldn’t exist, or exist in the same way at least. In referring to the subvisible world, it is from the title of the Lynn Margulis book with her son Dorion Sagen, “Garden of microbial delights: a practical guide to the subvisible world”, where they discuss microbial realms, our bacterial ancestors, viruses, bacteria, protists, and fungi.

For me, the term non-human subvisible world extends beyond this and is not necessarily even living, such as air, chemicals, microplastics, toxic waste, magic, and ghosts, things humans perceive to be not of ourselves. It is somehow the things that are in communication and affecting our bodies and existence, whether we acknowledge them or are even able to see them. While differentiating human from non-human is silly, as humans are inherently holobiomes of many different microorganisms, with the majority of our cells being “non-human”, this separation in the language is based on our perception of our “human” lens.

There is nothing wrong with human-focused narratives as; unfortunately, we are all human by society’s standards. To deny this, like the capitalists have been trying to do since before the industrial revolution, is a cruel act against nature to transform the body into a machine to extract labour-power to profit off most people, the working class. I find it disappointing to those who believe we are living in the Anthropocene, as I believe this term is highly misleading in that it is the capitalists’ fault for current disasters attributed to climate change and not the majority of humans.

Could you expand on how you navigate the concept of symbiosis to create purpose within your art?

If you take the example that all life exists because of a form of symbiosis, how does this perception of life change how we produce our art or organise work? A symbiosis of ideas that perhaps on the surface seem unrelated, for example, cyanobacteria and the working class, but has more in common when their stories ferment together to create a musical narrative. On the idea of working and collaborating with others, my thoughts and ideas transform into entirely new ideas when fused with others’ input, and maybe my ideas weren’t even my own to begin with.

For example, when we express emotion through a written song or poem, it probably will also reflect someone else’s similar thoughts or feelings. While we each are an individual, our realities can continue through collective thinking, thinking not only of oneself and my ideas as my own. But of course, this can be conflicting when we live under a system that emphasises the individual over the collective. Even in situations encouraging collective thinking or working, it is all under the same umbrella built from this unavoidable individual importance.

Your work often creates complex networks of oppression as a form of collective resistance. How important do you think networks are when building collective resistance as a society? In what ways would you love to see this reflected by those who interact with your work?

While discussing symbiosis between toxic cyanobacteria and the working class during a revolution in a musical! It is already quite complex and out-of-the-ordinary; combining topics that seem unconnected is a way of beginning to form these networks. In my last musical about ghosts subtracting colour in a colour space to establish interruptions of production, I was interested in how to explain ghosts as manifestations of our material condition. For example, thinking about why these ghosts are here, as perhaps as a result of my stress, mental illness or trauma, as a result of the capitalist system that exploits me, a system that encourages and permits non-punished behaviours associated with sexism, racism, homophobia, transphobia, etc.

One must also question how I’m forming these complex networks from the privileged perspective of an artist. At the same time, I am still a proletarian, even if the system desires me to be labelled as a freelancer in the increasingly focused gig economy. Something I find myself now thinking a lot about is how art is used as a tool often to uphold ideals, expectations, or standards reflected by different groups in society. How can I make art for the working class, or what is working class art? Should I speak in a language that I understand and feel comfortable with, or should I try to speak in a way that is understood, a shared language? And whether we like it or not, we are all a part of a bigger picture, and it is pretty tricky to create art to form a collective resistance that extends beyond the art world or doesn’t alienate the very people you want to address. This is something I’m constantly working on, how to speak for myself while still being able to be understood.

You speak of expanding space as a way to redistribute stolen futures. How many of these spaces do you allow yourself to imagine? Do your projects live within these scientific/historical settings, or do they exist in a plane of their own?

The narration I created around the Holobiont installation takes place within a laboratory that plays with the inter-relationships of science and magic in relation to the history of capitalism, exploitation and extraction to make sense to myself somehow how we have come to his point in our story when everything is in a constant state of political disasters that keep over-spilling. And, then, through this fictional story, imagining how we could overcome the disaster, which I believe can only be achieved through revolution, a lot of sacrifices, and change, which for me is the foundation of what symbiosis is, organisms coming and fusing together to create something completely new, embedded themselves inside the tissues of one another, together with our past trauma, emotions, with memories and lessons from our ancestors, human and non-human, to forge futures that came make way for new forms of being. All these fictional stories I build are formed within the same universe that bleed into each other and manifest themselves as some way of helping myself cope; I don’t imagine or expect that they could change the world.

What advantages do you think the sound has in creating sentiments of love and symbiosis?

For me, my sound work and accompanying poetry / lyrical work is the essence of my work, as I feel I am more efficient in speaking in a language of sound to portray my emotions together with meaning in constructed ways that hit straight to the depths of the heart and cannot be interpreted any other way than what I imagined them to be. The act of creating and singing a song, especially when done with others, is an embodiment of love and symbiosis. Often the words, or the feeling, I am portraying through this song is something that many other people are feeling similarly to me. The meaning of love changes based on need and historical and environmental settings and can mean different things.

Still, as a form of caring and responsibility, it can be shown through the history of the working class and labour songs, for example. How a piece can linger for hundreds of years arises from symbiotic and collective resistance and struggle to pass on words of encouragement and knowledge to future generations. In terms of non-spoken “sound”, I think it has the beauty and grace to explain things that often our words cannot, and how it can be a tool to accompany or illustrate a deeper meaning to the narrative.

What does intimacy sound like to you, and what feelings/intentions did you centre when creating the compositions for Holobiont: Relics from the Revolution?

When I created the piece, I was graduating from University in the middle of a pandemic, and going to the university, there was practically no one there in a building usually full of students and teachers. And since I was graduating, I was allowed to be there physically. Before the pandemic, I had found the song from Brecht Ein Pferd klangt an, and the anger illustrated by the singer, primarily through a performance from Gisela May, resonated with me. Anger as an expression is something I have learned to express and was something not particularly easy for me. And I think through the expression of anger, in the environment of this very soft and intimate environment in the installation, “Holobiont” portrays controlled anger as a means of motivating initiative and movement in also understanding why anger is growing and how it is important to listen to our anger, our greed, hate, or jealousy.

What were some of your main influences when creating the Holobiont: Relics from the Revolution universe?

When I first began research for this piece, I took inspiration from artificial wombs depicted in science fiction films and animes, Imagining the symbiosis between the working class and cyanobacteria to be forming and growing within the very installation, as the sounds from the temperature and pH data from the cyanobacteria and air, envelops the visitors into the symbiotic relationship themselves. Theoretical and scientific inspiration as a foundation would be Lynn Margulis, Silvia Federici and Karl Marx, along with much different scientific research about cyanobacteria, specifically toxic cyanobacteria and other phytoplankton/micro-algae. For story building, I looked into works of fiction such as my Octavia Butler’s Fledgling, Leslie Feinberg’s Stone Butch Blues and Maxim Gorky’s The Mother.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

I do not know if it is, per se, my chief enemy of creativity, as for me; I don’t see my practice as something creative but rather something that I simply must do. But something that I feel is a more recent question when creating my work is how my identity relates to the collective struggle. Or how much of myself, my body, and my perceptions should or should not be a part of my work. And I think getting lost in caring about others’ judgements too much, mixed with a desire for my art “fit in” aesthetically with others, on top of the pressure to be physically beautiful or sexy or cool, has also held me back in creating something honest that reflects my comfort in the ever-changing, slimy, toxic, and dirty chaos.

I feel I’m in the process of unlearning this, embracing the mess, and finding out how to express my identity through the yuck, together with collective growth. As well, I always feel this instinct to protect my identity, how I feel and see myself, my past and my trauma, as I do not want to incorporate it and find myself stuck in how someone else defines me or having some part of myself I believe in, being monetised off of, or appropriated and used to bring forward ideals that I do not associate myself with.

You couldn’t live without…

One thing I know I can’t live without, but somehow I sadly go long periods without, is being close to (warmer) seas or oceans. Although I had a wonderful trip to Rüggen and the Ost Sea last summer, I realised while visiting the Mediterranean Sea last October that the experience of sitting alone and with the warm salty water is something I need and brings me calmness and purpose somehow. I enjoy the waves, the current and the feeling of being engulfed in the water while being slightly overwhelmed and in awe by my fear of powerlessness.