Text by Irem Erkin

Sound has a unique ability to transport the mind along time and space. A single vibration can evoke childhood memories—a familiar song playing during a family dinner, or the distant cry of a seagull recalling the shores of the hometown. This sonic journey blurs the boundaries between past and present, reviving echoes of places left behind.

Memory, in essence, is not just a collection of past moments; it is a living, breathing part of human identity. Sound, perhaps more than any other sense, holds the power to evoke memories and emotions, transporting individuals to distant times and places, and reminiscing people and places that have been left far behind.

In moments where the mind journeys across time and space, sound becomes the catalyst, drawing individuals into past places and experiences. This time travel, which takes you back to places once vivid, but no longer familiar, creates a feeling of displacement—a continuous negotiation between nostalgia for home and adaptation to a new reality. A fascinating paradox arises from the idea that distance can strengthen connections. The sentiment, Feeling more connected when far away, from the piece A Forbidden Distance within The Crossing project, encapsulates this idea. Created by Saint Abdullah, Rebecca Salvadori, and Eomac, this work captures the emotional landscape of migration, displacement, and the invisible borders that exist between them.

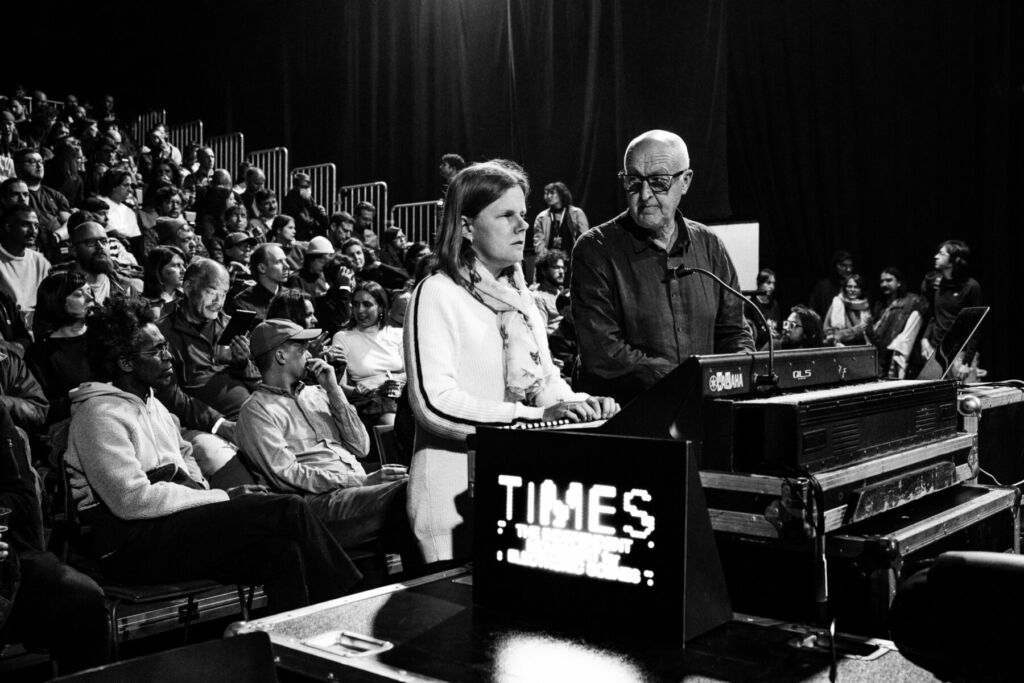

TIMES- The Independent Movement for Electronic Scenes

The Crossing is the first artistic creation of the TIMES initiative, a collaborative project uniting ten European festivals to produce original performances that blend music and visual arts. Along with co-curating artists and commissioning original works, TIMES aims to support, promote, and enhance diversity and sustainability in the music sector. Co-funded by the European Union, the initiative is a collaboration between Berlin Atonal, Elevate, Insomnia, Le Guess Who?, Nuits sonores, Reworks, Semibreve, Sónar, Terraforma, and Unsound.

This multidisciplinary project explores themes of migration, borders, and memory, bringing together artists, musicians, and researchers to examine the psychological and emotional impact of “displacement”. Presented in two chapters, the project dives into the complexities of migration, capturing the psychodynamics of the migrant experience through collaborative artistic approaches. More importantly, The Crossing illustrates how migration is not merely a physical transition but a profound transformation of identity and the self’s relationship to place.

Białowieża Forest- A Natural Geopolitical Wonder

At the heart of The Crossing is Białowieża Forest—a natural wonder that has become a site of significant geopolitical tension. Spanning between Poland and Belarus, this forest was once part of an expansive primaeval woodland that shaped Europe’s landscape. Today, it stands as both a geographical location and a powerful symbol of natural beauty and the stark realities of modern migration. The construction of a wall dividing the forest serves as a stark visual reminder of the divisions shaping Europe today.

This wall immediately recalls Doris Salcedo’s Shibboleth installation at Tate Modern, where a large crack in the museum’s floor symbolised the separation between cultures, social classes, and ethnic groups. Salcedo’s work highlighted not only the physical boundaries but also the invisible, psychological borders that marginalise certain communities, particularly migrants and refugees.

Like Salcedo’s work, which exposes the invisible barriers that divide people, researcher, filmmaker, artist and activist Lawrence Abu Hamdan’s 45th Parallel explores the complexities of borders—not just as physical structures but as sites where legal, political, and human contradictions collide. Set in the Haskell Free Library, a unique building that straddles the U.S.-Canada border, the work examines how borders are spaces of negotiation rather than absolute divisions. Through storytelling and performance, Abu Hamdan reveals how these boundaries—such as the Białowieża Forest’s Border Wall—shape the lives of those caught between them, reinforcing that migration is not just a movement of people, but a reconfiguration of memory, law, and identity.

In 2022, Poland constructed a border wall along its frontier with Belarus, which cuts through the ecologically significant Białowieża Forest, a UNESCO World Heritage site and one of Europe’s last remaining primaeval forests. Standing 5.5 metres tall and extending 186 kilometres, the wall was built in response to a politically charged migration crisis. Designed to enhance border security, it has drawn sharp criticism for its impact on both the environment and human rights. It disrupts wildlife migration, fragments habitats, and threatens species such as bison, wolves, and lynx, jeopardising the forest’s biodiversity. Simultaneously, it has left many asylum seekers stranded in harsh conditions, raising questions about the humanitarian cost of such measures. The placement of this barrier in an ecologically sensitive area continues to spark debates about the balance between national security, environmental preservation, and human rights.

For migrants attempting to cross, the forest becomes a place where nature and geopolitical conflict collide. It is a site of both survival and loss, where the experience of displacement is embedded in the landscape itself. Polish Nobel-winning author Olga Tokarczuk suggests that borders often do more than divide land; they serve as a deep, intrinsic connection between human and nature—an idea that resonates strongly within the context of Białowieża Forest.

Simona Kossak, a Polish biologist, ecologist, and fierce advocate for the Białowieża Forest, spent much of her life immersed in its depths, studying and protecting its wildlife. Living in a wooden cabin without electricity, with her husband, photographer Lech Wilczek, she dedicated her work to understanding the complex relationships between humans and nature. Her deep reverence for the forest is encapsulated in her words: The forest is a world in itself, one we are only guests in. It has its own rules, its own language, and its own memory. This perspective highlights how landscapes like ‘Białowieża’ embody histories that extend beyond human borders—histories now disrupted by geopolitical tensions and environmental threats. It is here that the first chapter of The Crossing is grounded, using the forest’s symbolic and actual borders as a backdrop to explore the fractured, often dangerous journey of those attempting to enter the EU.

Białowieża — The Sound of a Divided Forest

The first chapter, Białowieża, immerses the audience in the depths of the forest, brought to life through the sonic work of field recordist Chris Watson and the renowned Polish sound artist Izabela Dłużyk, who is blind and has a deep connection to nature’s acoustics. Dłużyk, named one of the BBC’s 100 Most Influential Women in 2023, collaborates with Watson, whose career began as a founding member of the pioneering Sheffield-based experimental group Cabaret Voltaire, in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Since then, Watson has focused on capturing wildlife sounds from around the world.

Their work Białowieża is presented in total darkness with multichannel audio, allowing the listener to experience the profound connection between sound and memory. In their piece, the bird songs and the natural breath of the forest are suddenly interrupted by the harsh sound of human screams, shattering tranquillity. This clash of sounds confronts the audience with the brutal reality of political conflict intruding upon the peaceful harmony of nature. The collaboration creates an experience that is more than auditory—it is a visceral exploration of how sound evokes memory and serves as an emotional bridge to the past.

A Forbidden Distance — The Emotional Fragmentation of Migration

The second chapter of The Crossing, A Forbidden Distance (a name inspired by an old song dedicated to Białowieża), shifts its focus to the emotional and psychological fragmentation that accompanies displacement. This project is a collaboration between artists Eomac, Saint Abdullah, and Rebecca Salvadori.

Eomac, the alias of Irish producer Ian McDonnell, is renowned for his raw, visceral soundscapes that seamlessly blend obscure samples with innovative sound design. Iranian-born brothers Mohammad and Mehdi Mehrabani-Yeganeh, also known as Saint Abdullah, introduce a distinct palette of sounds —a charged and anxious yet assertive blend of minimalist dub and Iranian samples. Rebecca Salvadori, a London-based artist, brings her expertise in video art and documentary, emphasising non-hierarchical layering and intricate sequencing of audio to footage. Her works are constellations of highly personal yet elusive elements—multifaceted portraits of moments, people, and environments.

This mesmerising audiovisual work explores the experience of displacement and the sense of self that is often lost or reshaped in the process. Displacement is a theme explored in other impactful artworks, such as Shirin Neshat’s video installation Exiled, which challenges the notion of borders as mere geographic lines, instead focusing on the emotional and psychological boundaries that define the condition of exile.

Reflecting on his personal experience with displacement, Eomac shared, As an individual, I have had my fair share of displacement. Thankfully, none of it was violently forced, but I moved around a lot as a youth. On the downside, I grew up with a sense of being ungrounded. On the flip side, I developed a love of travel and an openness to other people, other cultures. As an artist, I take inspiration from displacement, despite the many challenges it presents to people. Modern music would be far less interesting without it. Through all the pain of personal experience, people always make art, and that is a very human, and therefore hopeful, thing. Creation is always more powerful than destruction. The human spirit may be displaced, but it can never be crushed.

The visual component of the work, created by Saint Abdullah and Rebecca Salvadori, incorporates recordings from Saint Abdullah’s mother, capturing their childhood and her unfulfilled dream of becoming a journalist. These personal recordings, deeply edited by Salvadori’s brilliant artistic eye, intertwine with Eomac and Saint Abdullah’s music, harmonising deep electronic samples with cultural essence. The result is a hypnotic narrative that stirs the soul.

Displacement often carries both personal and historical weight, shaped by diverse cultural narratives. While Salvadori brings her Italian heritage into the process, she also reflects on how listening to her collaborators’ biographies became an integral part of the project. It was fascinating to share our personal histories and somehow build a new collective one together, she remarked, emphasising how the blending of artistic identities helped shift the focus to the work itself rather than the individuals. She described the process as striking a rare balance between playfulness and depth.

This depth translated into profound audience reactions as the performance travelled through various countries. Reflecting on its Berlin Atonal premiere, Salvadori noted the striking contrast between Kraftwerk’s industrial grandeur and the intimacy of the work: The environment affected the perception; there was a very dense silence, and I perceived time moving at a different speed. In Braga’s SEMIBREVE, however, the performance fostered a unique connection. Salvadori recalled sitting on a bench with Eomac and Saint Abdullah after the show, as audience members approached, to share how the piece resonated with their personal histories or simply moved them on an emotional level.

Memory, a key element of the piece, has an uncanny ability to collapse time. Salvadori shared how converting an old VHS tape from her childhood felt like time travel: It was one of the first times I held a camera, and the excitement of discovering the zoom effect is quite evident. Editing the footage revealed organic shifts in focus: Sometimes it was me looking at Eomac and Saint Abdullah working together; sometimes it was me looking at myself working with them… sometimes it was the work itself looking at me and telling me things.

Memory of A Landscape

The line, feeling more connected when you are far away, encapsulates the emotional paradox woven throughout the piece. Salvadori described this sentiment as deeply personal: I have left, I have come back, and I’ve left again… I feel I belong everywhere and nowhere. So the desire to belong makes me feel things. This longing, paired with the work’s universal themes, invites audiences into an intimate and introspective exploration of distance, connection, and identity.

Saint Abdullah reflected on the blending of personal identities into a cohesive artistic language: I think Rebecca Salvadori’s approach to filmmaking—the techniques she employs—has a lot in common with how we work with sound as a material. She builds and samples archives, creating cross-pollination and meaning through the vast catalogue of human experiences, people, and places she has captured on film. She also works in the moment, creating life. Our collective temperament was made for each other. Our constant searching, right up to the end—what will the story be?

Contemplating the challenges of confronting their past, he continued: It was heavy for me to constantly tune into our past, condensed within eight weeks. The videos capture moments in our lives that I sometimes wish never existed, or had never happened to us. My sisters can’t watch them because of their own relationship with the hijab. These videos were as real as they were imaginary—a portrayal of life in the West, directed by my mother to ensure that those in the East realised that we were okay, that we could sustain our Iranian-ness.

Eomac also reflected on the universal resonance of the piece: The beautiful thing about the response so far has been how universal and emotional it’s been. People have been affected by the piece on a deep level. Some have told us it reflects their personal stories, while others, with less direct connections to the subject matter, have still resonated with its emotional quality. We tried to be as vulnerable as possible in making it, and I think this shines through, helping audiences to respond in a similar way—a human connection.

Through sound, memory, and personal narrative, The Crossing invites us to confront the emotional and psychological toll of displacement. It underscores how art, whether through immersive soundscapes, film, music, or live performance, can offer a deeper, more human understanding of complex socio-political issues. Saint Abdullah further reflected: Honestly, I didn’t expect people to like it as much as they seem to have. I just knew this was a story I always hoped to tell, but didn’t know when, how, or with whom it would happen. What even was the story? It couldn’t just be a nostalgic, escapist moment.

This questioning of narrative and identity resonates with other artists exploring similar themes, such as Japanese vocal performer Hatis Noit. In her single Angelos Novus and its AI-generated music video by Yuma Kishi, Noit delves into cultural displacement, drawing inspiration from Paul Klee’s monoprint and Walter Benjamin’s essay Angel of History. Noit, a Japanese artist living in the UK, has long explored the boundaries of identity, particularly when mistaken for individuals of other Asian nationalities. To visualise this fluidity, she collaborated with two other Japanese performers of varying genders, highlighting both their similarities and uniqueness. Kishi’s use of Generative Adversarial Networks (GAN) technology further emphasises the blending and mutation of identities, mirroring Noit’s introspection on cultural and personal identity. Noit’s work is just another example of how artists are engaging with themes of migration, displacement, and shifting identities.

In a world increasingly defined by walls and borders, The Crossing offers a much-needed reminder that the stories of migrants are not just political issues—they are human stories. The project intertwines environmental, personal, and historical narratives to connect us to the shared experience of displacement. In doing so, it underscores the importance of empathy, of seeing humanity in every journey, and of understanding how the interconnectedness of people and landscape shapes the world we inhabit. The Crossing is a poignant reminder that even amidst the walls that divide us, there is hope in the stories we tell, in the collective memory we share, and in the spaces we continue to cross.