Interview by Alexandra Gilliams

Working across drawing, painting, sculpture, photography, and video, Caroline Corbasson investigates the mysteries of the universe with plenty of room for experimentation. Exploring monumental questions on both micro and macroscopic scales, her work is imbued with years of research and a sensitive, poetic disposition.

Corbasson collaborates with scientists who study astrophysics, neuroscience, and more to render technical knowledge accessible and highlight the beauty of what is factually known through science and the obscurity of what is unknown. After all, many of these scientists are searching for the origins of life, which arguably carries elements of mysticism and spirituality within it. This undertaking is pursued through a solitary practice at the shared studio space Poush in Paris but also through the physical exploration of ethereal places that are largely inaccessible to the public.

Her work initially examined nature, light, and using different optical instruments through drawing and sculpture. As she was led intuitively to explore larger parallels between the earth and space, she began translating her analyses across these two mediums and additionally through film, painting, and photography with graceful ease.

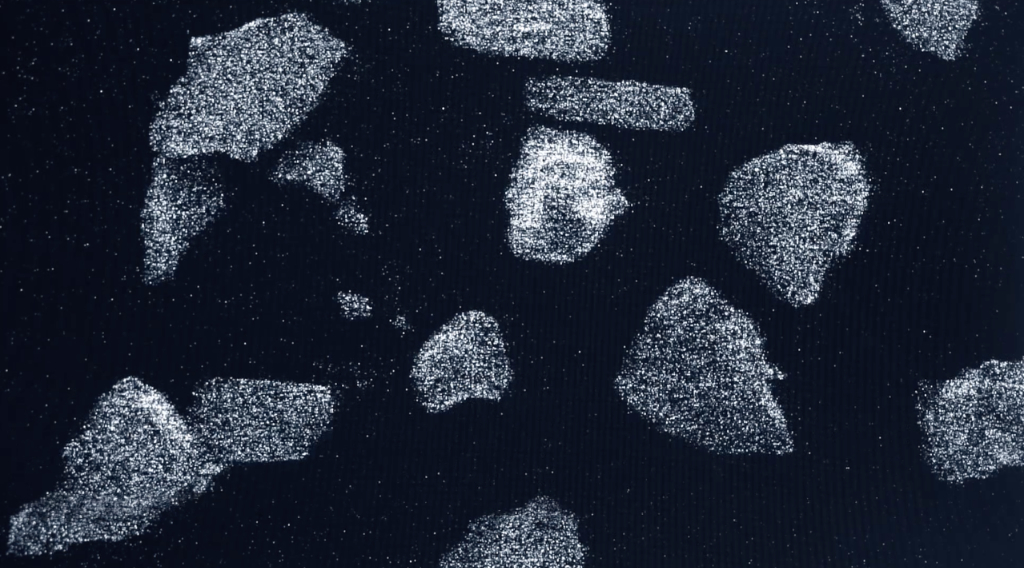

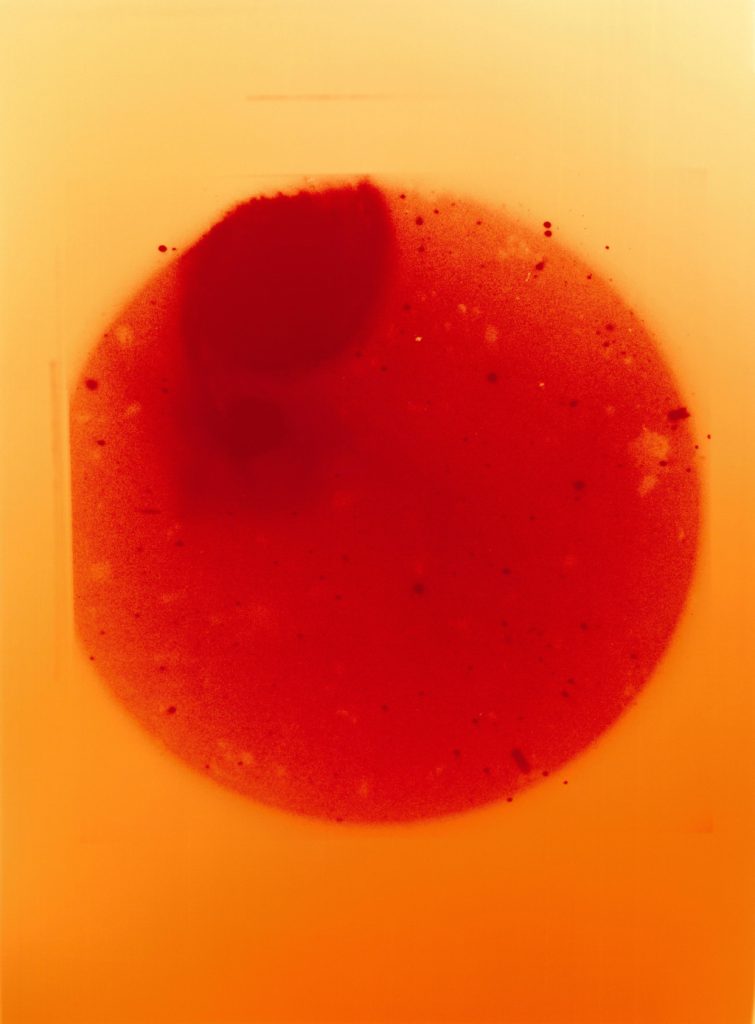

Part of her studio practice lies in iconographic research for reference photographs of celestial marvels that were taken using telescopes. She creates large-format charcoal drawings of these observations and uses found negatives to create prints in infrared and ultraviolet hues, suggesting the extreme temperatures found in space. Her series of photographs entitled Pollen recalls the theory that life on earth began from stardust. The scattered stars echo what the artist calls a “fertile dust” that she alludes to as pollen. Her work seems to be a manifestation of the Hermetic phrase “as above, so below,” meaning that what happens on earth is reflected on a spiritual plane or that phenomenon happening within and around us is related to that which is occurring in the stars.

In 2017, she began a series of films exploring otherworldly environments with ATACAMA, when she visited and filmed one of the world’s most important observatories in the Atacama desert in Chile. At 2635 meters above sea level and far away from any light pollution, the VLT or “Very Large Telescope” has been an important tool for major astronomical observations. It is located in the driest non-polar desert in the world, an environment that is so closely related to those in space that Mars expedition simulations have been made there.

She made a second film, À ta recherche, during a residency at the Laboratory of Astrophysics in Marseille, where scientists are developing a telescope to study dark energy. The instrument is so powerful yet fragile that not a single speck of dust may enter the room. Throughout much of her work, she challenges humans’ tendency for factual perfection, a powerful notion particularly prevalent in science. The third film in this series will be based on an observatory that is tucked away in a mountain in Japan.

Corbasson draws curious parallels in her work that evoke earthly and stellar occurrences’ power, beauty, and wonder. She recently released a new film entitled Physics as a part of a residency at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (EPFL), and she is a winner of the Mondes Nouveaux prize, a prestigious grant given by the French government to artists in response to the Covid-19 crisis.

I find the relationship you make between the micro and macroscopic to be captivating and perhaps a bit existential, as well. What was it at first that made you want to pursue creating work around this relationship between the “infinitely large” and “infinitely small,” as you have put it many times, and what does this idea mean to you?

The observation of nature has always fascinated me, so I quickly became interested in the instruments used for observation: those that take us to the scale of the minuscule and those allow us to look at vast dimensions. There is this permanent back and forth, but in both cases, the idea of going beyond our physical capacity of vision exists. There is a search for something that cannot be seen with the naked eye. It is a revelation of the invisible in both cases. I like to mix the two so that we no longer know at what scale we are situated because we can so often confuse them. It’s quite comforting and is something that’s been within me for a long time. Also, my father and grandfather work in optics, so I would say it’s from my childhood too. I’ve always been surrounded by instruments like eyeglasses and microscopes. My grandfather also worked for NASA! And spiritually speaking, I was raised Catholic, but I became a bit detached when I began questioning life and its meaning. I was always rather moved by that. The story of dust is very present in faith and spirituality in that we technically are “dust.”

I wanted to congratulate you for being one of the winners of the Mondes Nouveaux grant here in France. Could you tell me about the project that you are in the process of creating around the Pic du Midi mountain?

It’s a film that will narrate an event that happened to me and links astrophysics with neurosurgery. There are methods for treating the brain with gamma rays, which are present in deep space. More specifically, it’s based on a very dramatic summer in 2013 when I discovered that my mother had a brain tumour and would be treated with gamma radiation. That same summer, I climbed the Pic du Midi mountain thanks to an astronomer friend who invited me. Observing the sky saved and deeply healed me. I was to be able to take a step back and connect with the universe. I reached a certain confidence that I strongly felt at that moment. The film will be told as a cross between documentary and fiction through interviews conducted with surgeons and astrophysicists. I will ask these scientists in different fields the same questions. It will start from a very intimate story, but I will make it as universal as possible. I will detach myself just from the scale of my intimacy to tell a story that won’t necessarily be dark but actually quite bright.

You create drawings, sculptures, photographs, videos, and installations. I can imagine that the processes that you undertake vary greatly, but I am curious to know what kind of research you do before beginning a piece?

There is documentary research and, very often, a phase of iconographic research where I immerse myself in atlases or books and a lot on the internet. I’m currently researching images taken from surveillance cameras. Usually, I’ll have a fixation on something and begin looking for source images. The medium comes afterwards in a very intuitive way. Right now, I know that I need to be in the studio, so I’m going to paint and continue a series of paintings this summer, exploring stretched canvas as a support. I am, of course, still pursuing the moving image, but these projects require an investment and are big productions with a large team. I’m still balancing this with a solitary studio practice. I like to have both.

Where do you go, or what do you do when you’re in need of inspiration?

I regularly go to libraries in Paris, for example, the library at the National Institute of Art History. I also like the Natural History Museum here. It’s a place that allows you to travel a little bit without actually travelling, but before Covid, I travelled a lot. I went to Japan and Chile, and I go a lot to Canada because I have family there. There are still many ways to get inspired by what we have on our doorstep. But right now, I clearly need solitude. My life hasn’t given me much since I had my child. It’s very different for me now, I used to have freedom and independence and it’s definitely changed my practice. I don’t have a day when I’m alone, so I have to find little moments to create work.

During one of the lockdowns, spring arrived, and I couldn’t take being inside anymore. I started to become interested in starlight reserves. There is also one of these at the Pic du Midi mountain. They are one of the rare places on Earth where you can still observe the stars because there is no light pollution. I wanted to go there and make a herbarium of flowers so I could cultivate flowers that would have grown under starlight. It’s more poetic than realistic, but these flowers technically did receive a very distant light from the stars. I collected, dried, pressed, and framed them.

Most of the mediums that you pursue are fairly traditional. It’s interesting to find inspiration in very technical instruments such as telescopes and microscopes, and once you have your desired image, you frame these larger (or smaller) than life subjects onto pieces of paper. Last year, however, you exhibited Colorscape, a project in which you tapped into technology as material by creating a video sculpture using LED lights. Could you talk to me about this project and explain this leap in a technique that you made?

Yes, it’s a difficult topic for me right now! It’s very technical, and it drives me crazy. Colorscape is a video of computer-generated images that propose sky landscapes all day long. It’s been placed in an office because, for me, offices can be so sad since they are closed off. I wanted to offer them an opening… kind of like a window, that would allow them to observe the sky at different times of the day and at different scales. Sometimes there are images of the Earth through celestial, earthly, and terrestrial clouds, and other times the images are from space. The designer and I used real images that we later animated. The idea is that it changes according to the seasons and the time of day, so there are times when the colours are more soothing and others when they are more stimulating. We made a program that lasts around 16 hours during the day, and at night, it turns off. It’s an invitation to contemplate. It’s true though, that the technical aspects took a lot from my creative process. Since it was a prototype, it was really necessary to think everything through very thoroughly. Right now, I’m really leaning more towards a return to painting. When I work on something that is so complicated, I need to reconnect with the means that allow me to be more independent.

You’ve travelled to an observatory with one of the world’s largest telescopes in the Atacama desert in Chile, you had a residency at the Laboratory of Astrophysics of Marseille, and you visited an observatory in Japan that is nestled inside of a mountain. These all sound like spectacular places to be immersed in, and I imagine there must have been an intense connection between yourself and the cosmos there. Could you describe the feeling you had entering these vast laboratories for the first time?

I went specifically to the Atacama desert to visit an observatory with an instrument called the “Very Large Telescope.” Before I left for my trip, I was so obsessed with the idea of this observatory that I didn’t really anticipate how shocking the desert would be. What influenced me the most was this feeling of a blank page in your head; suddenly, everything became very clear. It was a lucidity that I had never known before, and it changed my life. When I came back from the desert, I did a lot of reflection; it was not necessarily easy. These places are also quite inaccessible to the public, so I had a desire to share my experience and reveal something hidden from these places.

My project in Japan is completely different because the scientists there make astrophysical observations that also occur on Earth. Being in Japan felt like landing on another planet too, which was very inspiring. The laboratories I visited are anchored in their mystical landscape, which made me think of how the desert and Japanese mountains have always been a place for a retreat… In the end, it was nature that interpolated me more. I visited and filmed the observatory—it was incredible—but when we left, there was a street lamp just outside with butterflies fluttering around it. They were also on the road, in the process of dying. It was very strange, so I started to focus on the butterflies… I was looking for something very technical, very particular, but in the end, it was the little butterflies that attracted me the most.

That makes sense, knowing that this project will also be about different forms of metamorphoses. You have mentioned that one of the specialties of this laboratory in Japan is the observation of neutrinos, which are “the lightest of all the subatomic particles that have mass and are also the most abundant massive particle in the universe.” Without giving too much away, could you give me a hint on the relationship between this laboratory and the idea of metamorphosis that you are exploring?

When we think of space, I think a lot of us imagine something very fixed, with each star having its place. But there are very violent events that are constantly happening, like stars that enter into a fusion that metamorphose. The phenomena of metamorphosis often occurs in space, with waves and neutrinos reaching us as a consequence of these events. The idea is to draw a parallel of these events at any scale.

What were your days like while you were in residence at the Laboratory of Astrophysics of Marseille in 2019?

I was observing the construction of a special telescope called Euclid which will be used to map dark matter. I was in an extremely sterile room with many protocols just to enter. We had to wear a suit, masks, and gloves—the dust is actually eliminated from this site, so this idea also interested me. I was going to give a poetic look at their gestures, their protocols, and their ways of behaving with this very technological and precise machine. What interested me was how they want to achieve sometimes very demanding measures, but that all this is done with the human hand—you will see in the film!

These films explore distinct laboratories around the world, and there is a poetic element through the ethereal, scenic shots that you captured, as well as your choice of sound and narration. What is the common narrative that connects these three films, and what kind of ideas and emotions are you ideally trying to evoke with them?

There is this story of scales with the micro and the macro. There are also the instruments of measurement and observation, and then I would say that in all the films the question that comes up is “What are you looking for? And why are you looking for it?”

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Comparison. I find it challenging to keep creating at my own pace, regardless of how quickly things are going for other artists.

You couldn’t live without…

My daughter Aria.