Interview by Olya Karlovich

From the metronome to music boxes and mechanical pianos — people have been experimenting with automating instruments since the old days (‘with increased frequency since around the second half of the 18th century’), blurring the lines between acoustics and technological innovations. But if before the musical potential of such devices was quite limited, and they were used exclusively for entertainment purposes, their modern descendants can play a significant role in the creative process, expanding the expressive possibilities of the artist’s practice.

As Godfried-Willem Raes, head of Robot Orchestra, noted in the Computer Music Journal article: contemporary computer-controlled instruments can be designed to offer finer control over musical parameters (e.g., pitch, level, timbre, timing) than humans could ever hope to achieve.

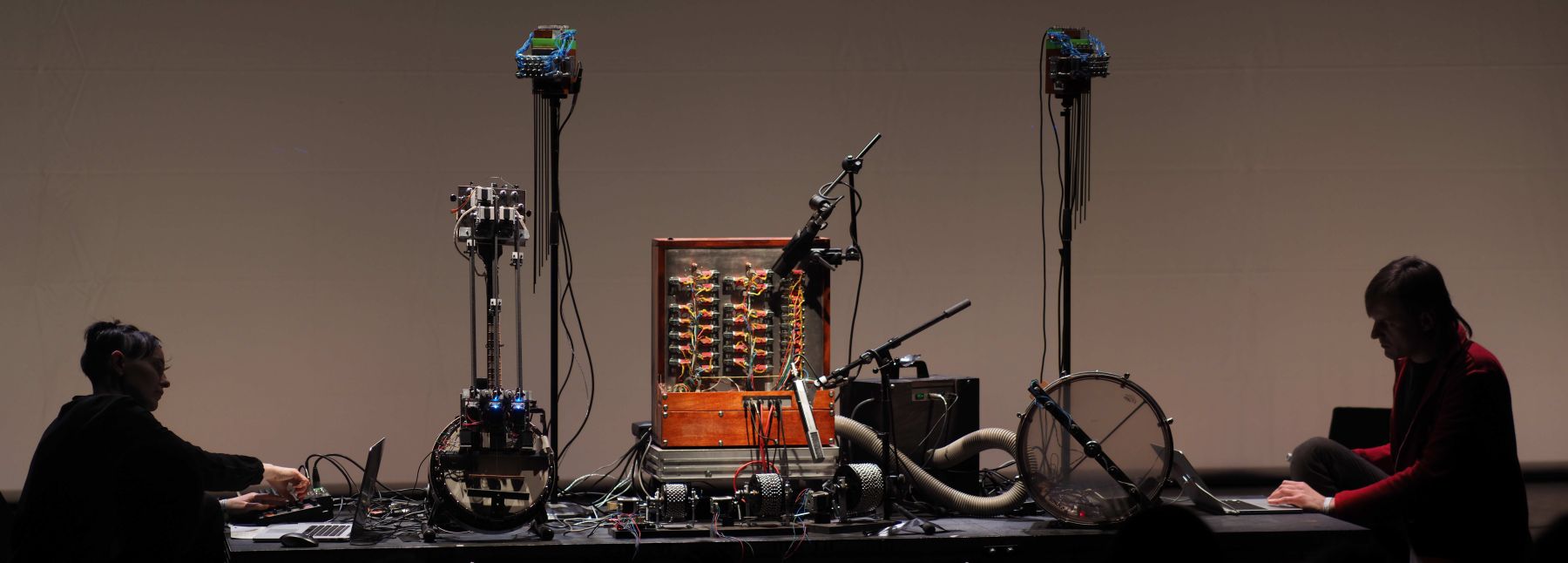

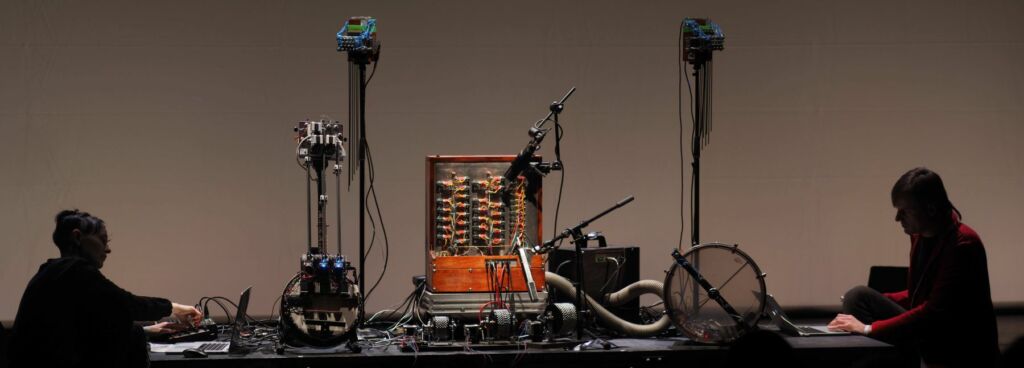

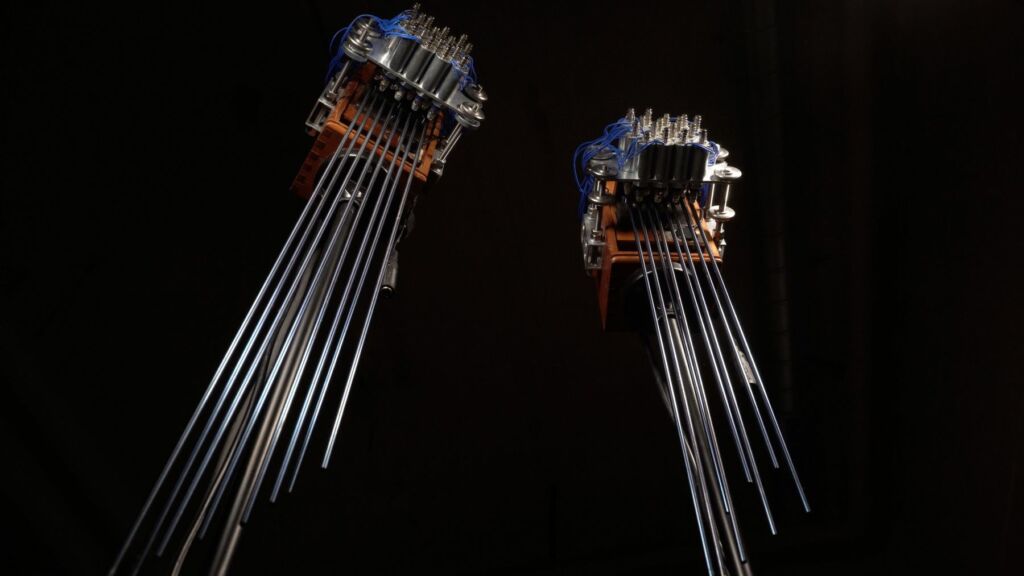

Initially driven by the interest of exploring territories where humans naturally cannot go, but music machines can, in 2011, Marion Wörle and Maciej Śledziecki founded the retro-futuristic ensemble Gamut Inc. Over the next few years, the artists fully immersed themself in the development of robotic instruments, acoustic but controlled live by computer. And today, they have in their arsenal such marvels of technology as an automated accordion, three stepper-motor driven cabasas, sine-wave driven tub, and more. The first Gamut Inc album Ex Machina was produced exclusively with music machines.

However, the ensemble does not stand still. They gradually shifted the focus from ‘building [instruments] to making the music itself’, addressing the questions: What else can you do with the machine? What music justifies the use of the automata? As part of their expansive research, the collective also curates special events. Last year, they organised AGGREGATE, a festival dedicated to interaction with a computer-controlled organ. On this occasion, Wörle and Śledziecki invited such composers as Mark Fell, Ellen Arkbro, Jasmine Guffond, and others to create new music for automated pipe organs, the instruments at the pinnacle of technical possibilities.

Always interested in extra-musical themes and experimentation with different formats, Gamut Inc also makes musical theatre. Their latest robot opera, titled Rossums Universal Robots, which premiered in 2022, is an updated version of the sci-fi play by Karel Čapek.

Among the new ensemble’s projects is the second Sum To Infinity LP (Morphine Records, 2023). It Is based on the Risset rhythms effect, listening to which you get a feeling of constant acceleration and deceleration of the tempo. The illusion is created by increasing/decreasing the tempo while fading between multiple rhythms with related speeds. Despite having a kind of arithmetic core, Sum To Infinity sounds not only rigour and, in a sense, restless but also vibrant and musical, in a kind of orchestral manner. According to press materials, in this album, Wörle and Śledziecki ‘combine custom-built autonomous music machines with haunting classical synthesisers to create a dense musical kaleidoscope’.

In the various Gamut Inc’s projects, in all their practice, one thing remains constant — this fascinating synergy between automation and creativity. After all, as Maciej Sledziecki states: Man and machine go hand in hand. And it seems to be both the most general and most accurate description of what the ensemble is doing.

You have been working with music machines for more than ten years already. How do you reflect upon this time in terms of Gamut Inc’s creative evolution and the development of the computer-controlled instrumental music scene in general?

More and more artists are getting interested in the potential that music machines have. When we started playing MIDI-controlled organs in 2009, it was very hard to find someone who was interested. Since 2018, there has been a real boom in contemporary organ music, and with it computer-controlled organ music – some call it “The New Organ Movement.” Commercially available products such as the Polyend Perc or Dada Machines have contributed to the popularization of machine music – a far cry, of course, from its heyday in the early 20th century, when machine music was still a major industry before being supplanted by the invention of the loudspeaker.

For us, organs like the Utopa organ at Orgelpark Amsterdam and the Logos Foundation from Ghent are the “gold standard” for robot music. The robot orchestra built by Godfried-Willem Raes is truly unsurpassed in its scope and ingenuity. In this respect, we are very pleased to be working with them in September on a large-scale musical theatre production at the Deutsche Oper in Berlin. We are no longer limiting ourselves to the musical machines alone but are also composing for the wonderful RIAS Kammerchor. The human and the machine go hand in hand. Also, on the new record Sum To Infinity, we are no longer strictly limited to pure music machines and leave room for synthesizers and electronic arrangements.

You come from different creative areas – electronic and instrumental (jazz) music. How do you combine your experience and knowledge within Gamut Inc? And what challenges did you face when you just started making music together?

When we met, we immediately made music together. First, with guitar and laptop for a while. Even then, the guitar was deconstructed, detuned and prepared to bring the two sound worlds closer together. We definitely had different ideas about expressivity and tempo in the development of forms and harmonics. That only came together over the years.

It was not until we were commissioned to compose for the infamous organ in the Kunst-Station St. Peter, which can be controlled by a computer, that we found our way to the music machine. It was simply the ideal expressive apparatus for us as a synthesis of acoustic sounds and electronic shaping processes, and it made us what we are as an ensemble. We are very happy to work with organs again since 2018, and we see the potential for new things there for many years to come.

As with your first Ex Machina album, you used custom-built autonomous music machines to make the new Sum To Infinity. Could you tell us how your work/creative process with these machines is organised? Has it changed over the years? What does the balance between planning and chance/intuitiveness look like in your process?

The idea that the process is organized is interesting. But with us, it develops rather organically – and also somewhat chaotically. When we started, we were fascinated by all the possibilities – what you can do with machines and what kind of machines you can make. That quickly led to us wanting to build way too much in way too short a time. Not all of the ideas came to life, and not all of the instruments were durable enough to stay with us for the long term. Some are waiting for maintenance for quite a long time. The instruments we are currently using are the ones that are still running stably.

Gradually, the focus shifted from building to making the music itself. What else can you do with the machine? What music justifies the use of the automata? What strategies of electronic music can be applied to it? What are the limits of mechanics – and what of perception? In the meantime, we have developed improvisation tools, but we now tend to plan and through-composed forms. The improvisation and experimentation now take place in the composition phase.

The core of Sum To Infinity is formed by Risset rhythms. Where did the impulse to explore this sort of sound illusion in your album come from? And what was the starting point for this work?

The (grand-) father of machine music in modern times is, of course, Conlon Nancarrow. When we looked more closely at his compositional techniques, one of the fascinating things about his music is his conception of tempo. In his Studies for Player Piano, he explored a variety of tempo manipulations. We learned about geometric and arithmetic series and began to play with the possibilities of a nonlinear grid. It turned out that the machines could play very well within that molten time. So you can still have objects that are aligned with each other as everything shifts.

What was your main compositional challenge while working on Sum To Infinity?

Time – haha! As soon as you work with curved time grids, the whole logic of what a beat is, where the groove is in the DAW, changes. It merges, but we still wanted to tie all the elements to this shifting grid. You have to get away from the idea that an accent on a 4 is going to do something you expected. That was a new experience for us. And it was a challenge to connect the micro and macro levels of the pieces. That was part of the fun, of course.

In the age of software, the production process can be endless; there is always something that can be improved in terms of sound. How do you understand that the work on the album/music piece is finished?

Fortunately, we’ve been in a constant stream of projects for a few years now – it can be very dense at times. So we have to make time for certain projects like this record. On the one hand, sometimes you wish you had more time available, but on the other hand, it takes some decisions away from you. Very quickly, you ask yourself: what can I achieve in such and such a time? How can I simplify an idea so that it becomes manageable? And then, when time is running out, this immense stream of ideas pours into your head. So basically, it comes down to the known fact that deadlines are good.

Within the AGGREGATE festival, you explore automated pipe organs as the greatest unique synthesisers. What other musical instruments would you be interested in reimagining/rediscovering with automation (perhaps you are already working on something new for the collection of your musical machine)? And, vice versa, are there any new digital instruments/tools that you feel have exceptional possibilities for artistic experimentation and need further development?

Wouldn’t it be great to have an instrument that could automate the air itself? You could generate the sound waves in any way you want… ah, wait – that’s the concept of the loudspeaker, and it already exists… All kidding aside – we currently stopped building, trying to figure out what is possible with the tools at our disposal. We are developing concepts and an extensive software library to generate a lot of MIDI notes and control data. From this, we create models that can be shaped and assembled into larger units. This makes it possible to get sounds out of traditional instruments – like organs – that are otherwise impossible. That’s what we want to focus on instead of always building new instruments.

Many musicians/artists today are delving into cross-disciplinary practices. With your musical theatre and other projects, Gamut Inc is no exception. What experience do you strive to create by combining different art forms – music/performance/dance/light – in your music theatre shows?

The synesthetic experience of music and performance or music and film has always fascinated us. We’ve been making music to feature films individually and together since the beginning. The film or the performance already dictates a lot of the form that the music can take. It’s like an additional powerful voice – or voices – that have to be considered in the composition. It is similar to music theatre – so many media are involved at the same time that limitation is important in order not to overload the overall impression. This is where one often reaches the limits of human perception. We somehow came to music theatre organically – we have always been interested in extra-musical themes, and have experimented with different formats: Live radio plays, and thematic concerts – until we became aware of the use of music in a military context and wanted to explore it more deeply. That became GHOST TAPE XI – our first music theatre. The experience works on different levels – between the sensual musical experience and the intellectual engagement. Language is such a powerful means of expression, immediately thrusting itself into the centre of attention… that has to be framed within the framework of musical theatre. Because if you can retell the play, you might as well not do it. It is the comprehensive overall experience that interests us.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

Fortunately, we always have several projects going on at different stages, so if we get stuck on one thing, we can move on to another project. When you come back to the problem, you usually have a solution because you are looking at the problem from a different angle. The philosopher Roger Bacon named four obstacles on the path to knowledge: respect for authority, one’s own habit, dependence on preconceived opinions and unteachability. So too much self-confidence as well as too much doubt…

You couldn’t live without…

We would say perspective. We always need a goal to move towards, and confidence that we can somehow achieve it. Without this perspective, life would be very different.