Interview by Adriana Ciotau

The nature of technology is explored in Greg Lynn’s practice in a way in which technology changes the way we perceive architecture and how we reimagine things. His interest in fields such as architecture, design, technology, human science, and philosophy brought his practice to be perceived as an interconnected space in which all of these fields converge. In his practice, the focus is on the process and the value of creation, specific to innovation experimental.

This interconnection of fields is explored and experimented with by both Greg Lynn FORM studio and the company Piaggio Fast Forward (PFF), where specialists such as designers, architects, and researchers gathered together in groups to discover ways of living through innovation and design.

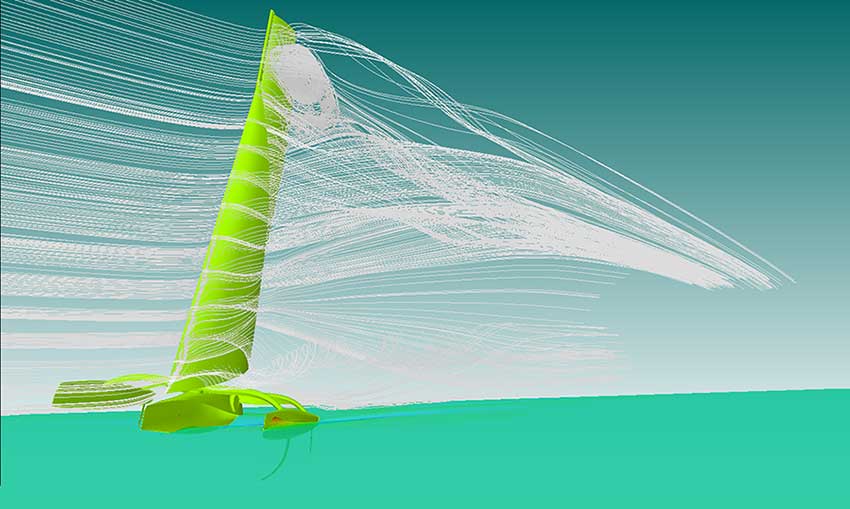

In Greg Lynn FORM studio, space is provided like a set of conceptual frameworks where projects are developed and grown as a network of ideas. Greg Lynn leads us beyond architectural and design form into a broader understanding of the relation of architecture and design to society through technology. Following this, Lynn has built an amazing array of projects, from buildings, such as Metyx Headquarters and Korean Presbyterian Church of NY, to design objects, such as the Microclimate Chair project, the 56’ Suncat project, and the Gita robot.

The Gita project represents an exploration of digital design and fabrication tools. It was conceived to question how to transfer a product from the virtual realm to the physical being and how will be trained following people. As a result, Gita embodies a character specified by the construction of a relationship with others. A robot which is an autonomous object configured like a character in a play.

The RV (Room Vehicle) is a 1/5th scale model of a residence, resembled as a cocoon form rotated in two axes on a robotic base. Several criteria need to be taken into consideration and had an influence on material selection for this model of residence. They focused on keeping the idea of a movable model. Therefore, the Room Vehicle was made of a carbon fiber fabric. Structural simulation of the form was used to determine the thickness of the material.

Greg Lynn focuses on design, on understanding the user, redefining problems, and creating solutions to prototypes. He goes further when it comes to ways of using technology perception for design projects. Like, for example, using a wearable computer to visualize the project proposal of the Detroit Car Factory. The wearable computer HoloLens lets you see holograms mixed with reality.

All these projects can be considered a projection of a technological society, where they have an impact and improve human flow.

Right: Render view, human eye

You studied architecture and philosophy at the Miami University of Ohio, and later you did a Master’s in Architecture at Princeton University. Could you tell us what did you learn during your time in both places?

As an undergraduate, I had studio courses every semester during all four years of study, so a total of eight design studios. I already had very sophisticated drafting and drawing skills when I came to school so the vocational aspect of these courses was familiar to me, and I was able to complete my classwork sometimes more quickly than other students. I could focus on design and not so much on acquiring skills. More importantly, I learned about the history of architecture and learned architectural precedents in depth.

This is something that is disappearing from students’ experience, and it was so very critical to me as well as the time I would travel throughout the United States and Europe to visit buildings I had learned about in school. I had the option to fulfil some coursework in the Western College program, where I received a Bachelor of Philosophy degree. I loved the courses that began with American Transcendentalism, which was at the core of the program. There I learned to write as we would have a paper every week for every course, and it would be returned to be rewritten every week over and over again until you turned in 10 papers at the end of the term. It was amazing.

I went to Princeton University to study with Michael Graves based on his early work that I had visited in Indiana and what he had done in his Five Architects period. I arrived and was immediately loathed by Michael for my interest in his early work and found the school was at the apex of extreme stylistic postmodernism.

The other students were very worldly and experienced and had worked in great offices around the world. The students used to have English tea parties for British expat faculty in the studio, and let’s just say it was a bit of a decadent place at the time that I found problematic. Many of my closest colleagues and best friends were students with me at the time, so it was an amazing place, but it was not a meritocracy and was a bit cult-like in every way that a cult operates.

I arrived along with the arrival of Michael Hays, who was there with other amazing history theory faculty like Tony Vidler, Alan Colquhoun, Bob Maxwell and other faculty teachings in what was at the time one of the few architecture PhD programs. So again, I was impacted by the depth of the history courses and lectures.

Could you tell us about the project that you did at the Miami University of Ohio in the philosophy domain? Who is your favourite philosopher, and why?

My diploma project was connecting American utopian societies with the recent projects of John Hejduk. While I was a student, I went to three consecutive two-hour lectures by John Hejduk at the University of Cincinnati around the time of the Berlin Masque project.

I also had gone with my parents to visit many Frank Lloyd Wright buildings in the Midwest as a child and had then spent the summer building at Arcosanti before going to college and was interested in when an architecture office turns into a cult as it did with Soleri and Wright’s Taliesin office.

The philosophers I was interested in as I was graduating were Luce Irigaray, Donna Haraway, Jacques Derrida and Edmund Husserl, who I had discovered as the subject of Derrida’s dissertation and was just mastering.

It has been years since you founded the Greg Lynn FORM studio. What was it that made you establish this practice? What is the current focus of the studio?

Before I went to college, I was using exotic drafting equipment and projective geometry to draw complex curved spaces. I remember drafting a threaded worm gear in perspective in Junior High School shop class. When I went to undergraduate school, I started using digital technology like Bentley’s Microstation to draft similarly complex spaces.

When I worked for Peter Eisenman, I had the same interests. When I started Greg Lynn FORM, I was interested in the use of digital technology to produce curvilinear spaces. Now I am pretty much doing the same thing, and nothing much has changed. I am a believer in having one idea in one’s lifetime and pursuing it to ridiculous extremes.

Could you also tell us what made you establish the company Piaggio Fast Forward (PFF)? How did you build up the practice and handle things like business development and operations?

In building the robotics for the RV Prototype House, we developed an App for driving it around in two axes. We applied that to driving furniture around the office and had the idea to give the furniture obstacle avoidance and SLAM (Simultaneous Localization and Mapping) so it could know where it was, when and what was around it.

Then by training the furniture, it could make decisions on where to be in the office. In this way, the furniture could be dynamic and intelligent, and the space would be more exciting, fun, and efficient and have higher performance. I priced out and prototyped it and took it to my friends at a few large international furniture companies and was told, ‘margins are low, and this looks expensive; we don’t know how to do this and are afraid of committing to technology that moves quickly; we know we will need to do this to survive, but we don’t want to do it now and come back when our competitors do it, and we will do it with you.’

So moving from the furniture industry to the light mobility industry was a logical next step. My friend and co-Founder Jeffrey Schnapp had just met with Michele Colaninno, Roberto Colaninno and Davide Zanolini from Piaggio, and that is how it started.

Piaggio Group is a multi-billion dollar publicly held global corporation so they are great with operations and business development, and I learn from and lean on them all the time. What Piaggio brings, most importantly, is a legacy of lifestyle consumer products. The Vespa, for example, is not just a scooter but a lifestyle. Building a robot that makes people more human, that gets them off of screens and out of cars, that focuses on walking in neighbourhoods and connecting with friends and family is only a mission because of Piaggio.

We are not making an autonomous burrito delivery robot but instead, the following robot that helps people be more active and connected because we want to be the next-generation lifestyle robot.

You have developed a series of projects focused on technology and design. What are you trying to accomplish with design and technologies, and, more importantly, what the design of one thing should accomplish?

I believe in all design needs to be high-performance in as many ways as possible with the fewest elements as possible. I love simple things but not simplistic things. Doing the most with the least and making something revolutionary in its performance is always of interest. So Innovation is a given, I would say, but not the focus. What is even more important than high performance as a focus is making something that will improve someone’s life.

A building that people will enjoy and connect with one another in, or a chair that people will fall in love with and will remember spending time at home or out in the world. Making something meaningful and memorable with a degree of comfort and support for their lifestyle is always what I try and accomplish. But familiarity and vernacular are, for me, too easy a path and not a challenge, so I always try to connect technology with comfort and supportiveness.

The interest in ‘the use of advanced materials and technologies for design and technologies’ can be traced throughout not only in your practice but also in your academic career. What do you teach at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, and how would you describe your teaching methods? What is interesting and important about your work as an educator?

I always teach whatever I am working on within the office. I am not a big believer in experimenting with students, but instead of transmitting knowledge. Because of this, I always bring whatever is the most promising and innovative thing going on professionally into the academic environment, where it can get taken in many different directions by students with very different experiences and knowledge.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

Not knowing what you don’t know. Very tough to be creative from a position of ignorance and even tougher if you don’t realize what you need to learn and practice.

You couldn’t live without…

The loss of the natural environment is deeply troubling.