Interview by Silvia Iacovcich

Crafting beauty from what could be seen as obsolete and exploring new sound depths with it almost sounds like Hainbach’s motto: the composer has a very personal approach to music. A prolific theatre, movie and gaming composer, he studied systematic musicology and English at the University of Hamburg, focusing on film music and Shakespeare’s dramas.

Moving to Berlin, he approached the realm of electronic sound productions and club music, shifting audio landscapes through many albums released on Opal Tapes, Spring Records and Limited Interest, amongst many others. Each release has its character – from the luscious orchestral arrangements and rapt xylophones of Acosta to the immersive, meditative states of Collision and the hallucinatory tranquillity in “Gestures”.

During the years, his interest in what happens behind the scenes has been merging with an engineering approach; in 2019, through a collaboration with SonicLab and developer Sinan Bokesoy, he turned a piece of equipment into music software named Fundamental, getting his hands into the gears.

When he’s not producing, you can find him on his Youtube channel, unstoppably experimenting with quirky objects like German knots, documenting his own experience mastering a new album, or diving into reviewing the next piece of esoteric music equipment, discussing avant-garde music techniques.

In between a thousand trips into synth amplifiers or the next gear’s review, he works with orchestras, composes on his Bechstein piano, dives into the core of instruments to let history survive in some way reflecting into history through the music itself, or makes an album entirely with a deerhorm organ, as in Gestures. And it’s fun to watch him carving out a unique path and not easily summarised, being entirely open to any new outcomes – it makes us want to have fun with him too.

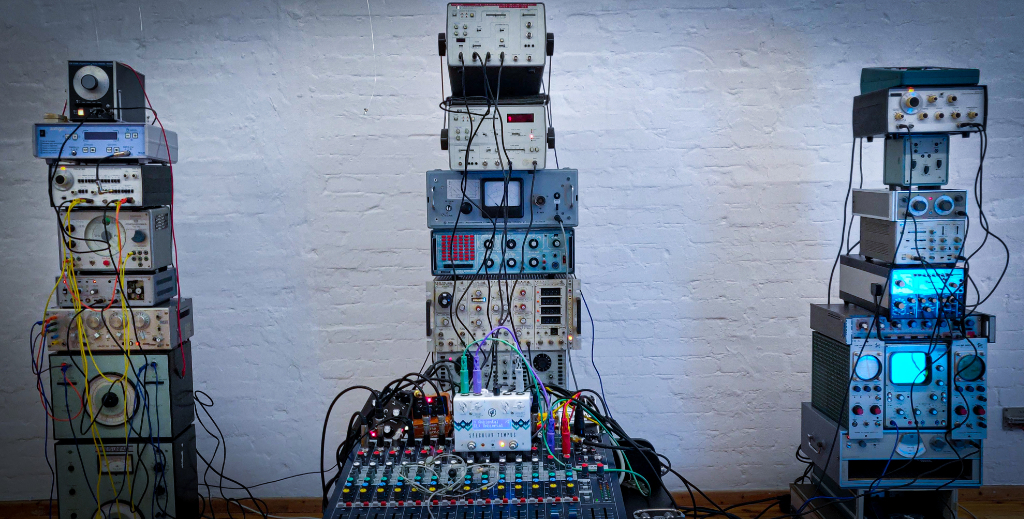

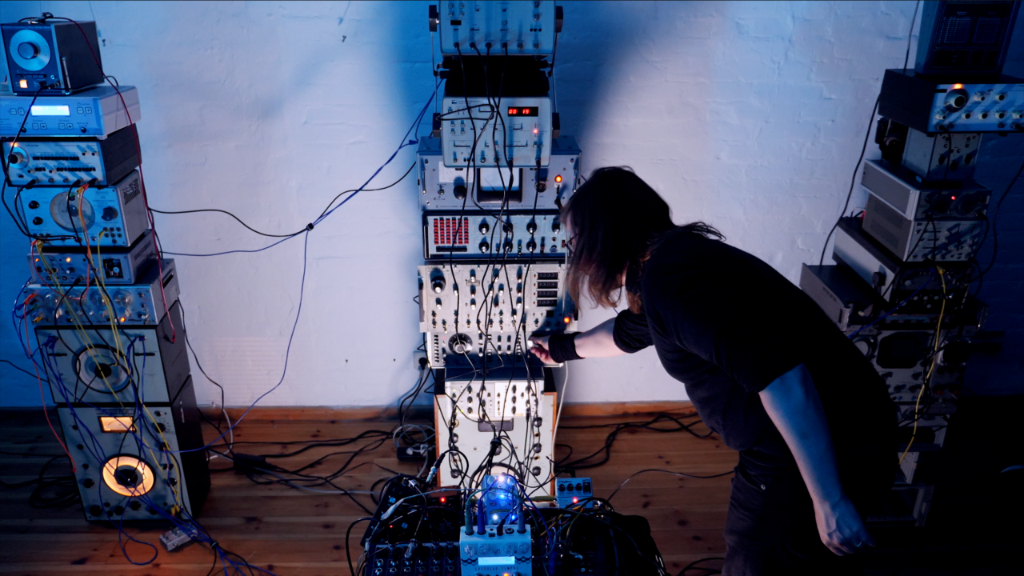

His latest project, Landfill Totem, is an all-around, exclusive journey into sound at its best multifaceted and experimental capacity. The project was born as a performative installation at the PNDT Gallery first when the composer realised – after two years of sticking up huge vintage pieces of research equipment found in a nuclear research lab – that it was time to hear how they sounded. Repurposed into musical instruments, they were arranged to look like gigantic statues, “totemic” figures turned into instruments carved from obsolete past manufactury, towers of a million faces and a million sounds, to which the artist gave life and integrated into a sound recording.

Through a collaboration with Spitfire, the project turned into a library of sounds you can get lost in – with a reservoir of pleasure for insiders. Diverse textured sounds mix funky groove and garage, mutating into voices, space from ambient nostalgia to curt, retro-futuristic ultramodern sounds – all completely brand-new and functional to a composer’s underscore, dense with high contrast flavours for the listener.

Landfill Totem is a many-sided, elastic artwork – a test equipment library, a sound that becomes an instrument (or vice versa), a sample made into an avant-garde gallery performance – finally, a journey into how technology has shaped our lives and sounds within our existence. The concept itself makes your brain go wild, following the idea that progress doesn’t necessarily cause destruction – and we don’t need to see this at first naturally. Still, we can retrace the steps of humanity through the beauty of engineering technology, assembled for their latest song.

Your work spans various mediums – musical robot lyrics, orchestral pieces, experimental electronics, theatre, gaming, and film. How did you become interested in music production? What piece of gear, instrument or person inspired you the most through these years?

After I got into a band with friends from school, I quickly got hooked on making music. Weekly sessions would not do; I needed to create independently and experiment. I loved hearing dubs of John Peel’s show on the free radio in the Black Forest; the music I heard was nothing I had encountered in my little town. I wanted to create these sounds free of connection to the physical world, so I used a boom box radio borrowed from my then-girlfriend to add noise and synthetic bleeps, sweeping the dial.

At the same time, my right and played the piano to an organ sequenced on the cheap keyboard I used in the band. All were tracked to a cassette recorder and later Cool Edit 96 on the MS-DOS. I also dabbled in trackers, but Piano always inspired me. Still, I wanted the tension of noise and synthetic sounds to lift to different places, and the processing capabilities of digital fascinated me.

In your latest project, Landfill Totem, you recycle and reuse outdated nuclear research lab equipment, particle accelerator computers and bits of old gizmos to create a full-length album – how did you work on the integration of these old equipment pieces into building real instruments and what were the challenges during the album production?

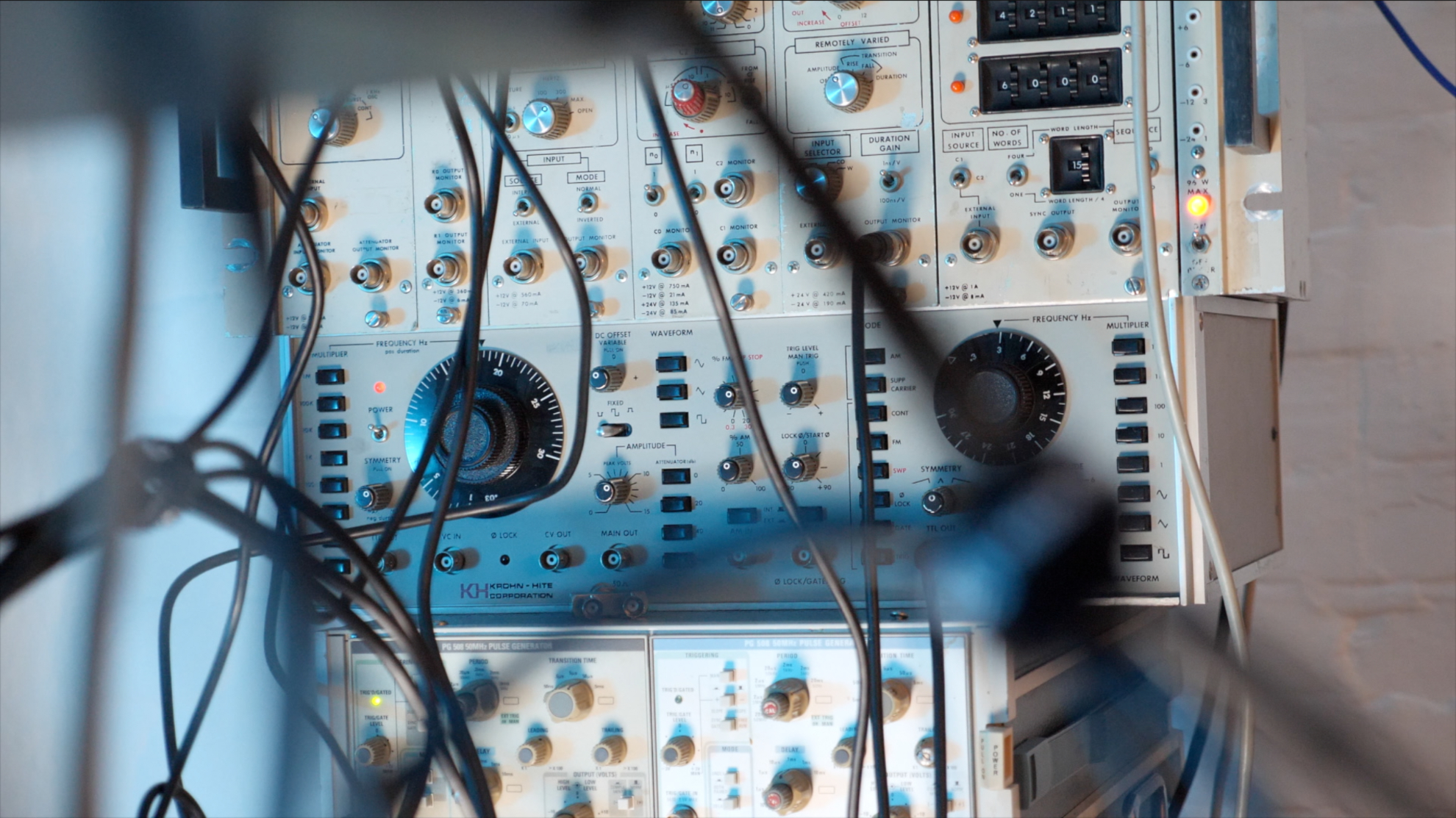

They kept dying on me. I would set up a track, record it, have a coffee and return to the smell of burned electronics. The dying function generator leads Funktionsverlustr – its swansong is a samba-eske melodic rhythm. Usually, this would drone, but in its destruction, it sang. Integrating all these together is a mess of adapters into adapters, a spider web of cables, my own forgetfulness of what goes where and tiny electric shocks. It is a bit like that scene in a crime movie when the detectives trace lines from suspect to suspect on a giant board.

Landfill Totem inspects our human revolution and the environmental cost of progress, connecting past and future using totemic images and industrial sounds – how did you approach the creative concept from the abstract idea to the physical performance, incorporating these different layers of meaning?

I am not much of a conceptual artist, but the first impulse for this was born out of necessity – in my hunt for beautiful old machines to see if they can play music, I had to accumulate a lot of them on chance—no way to tell if it would work, or work for musical purposes. I quickly ran out of space in my studio. When PNDT Gallery in Berlin asked me if I wanted to do a residency, I immediately knew that I had at least a storage space for the heaps of dusty equipment.

As I entered the white room with a van full of stuff, all the gear looked tiny compared to the space. So instead of setting it up in a playable wall, I had to try something different – I don’t know why, but I made a stature. And another one, then a third. They wobbled precariously and looked dangerous to touch, and honestly were because I never fixed them in place. This way, I could fill the room wildly once I spun the cables to the mixer and between them. What happened on this first day of setup made the Landfill Totems come to life. They looked like markers of a civilisation’s past; the best of their time become superfluous and destined for a landfill. So you could say they told me what I was doing.

Gestures is an introspective album that explores the sense of loss, rich with ethereal atmospheres and dreamlike textures, forging an organic sound with the sole use of the deerhorn organ: why did you choose it, and how did it influence the final result?

That album was recorded on holiday in my parent’s home. My father had died just a few months before, and I could still feel him in the space. So when I decided what to pick for this trip, I chose something that would embody that intangible sensation, an instrument played without touch. The Deerhorn Organ, and for that matter, all of Peter’s instruments, are very emotional instruments; they enable complex storytelling. There is a tone to them that makes them almost organic, not like synthesisers at all.

You experiment with an extensive range of radical mediums. At the same time, you use historical and time-honoured instruments like your old Bechstein piano to create sounds – how do you shift and balance tradition and innovation in your projects?

I like to move people with my music. Traditional music theory and instruments are like shining a light into the dark; they give you something to hold on to while the sound world around you collapses. There is a piece on my album “Schwebungssummer” – It will stay dark – that uses the piano just like that. It’s the familiar that draws you in and helps you understand the depths of droning, bleeping, beating test equipment.

Your career interlaces music from different angles – in 2019, you worked with SonicLab and developer Sinan Bokesoy into turning a piece of equipment into music software – Fundamental. Exploring from inside the gears – how was creating software that makes music?

It was a fascinating process, surprisingly easy as ideas flowed between Sinan and me, complex in the details of pure math and how to present something this new yet historical to the people. In general, what I aim for with my instruments is to take something little known of the past, add impossible ideas and then adapt it for the musicians of now. I aim to make things that people do not know they need until they hear them.

You are constantly exploring new channels, from Youtube blogger to lyricist to film composer. What are your following projects, and how do you imagine yourself in the next 20 years?

I have a few more ideas for musical instruments that I want to follow through – nothing I can share now, but it follows a similar pattern. After two dark and hopeless test equipment records, I will return to Seil Records with a fragile ambient album.

This April, an augmented reality app that I scored for will be released with the support of Goethe Institut in Tallinn, Estonia, and maybe travel to different cities after. In June, I will work with Amplify Berlin to mentor two artists to create music and their live performance. Then I hope it’s safe to travel again, and I will go to places at the root of electronic music and cover them on my channel.

In twenty years, I hope to be in the middle of realising my orchestral ideas – I loved working with a full orchestra in Trier a while back, and I don’t want this to be the only time I do this. Hopefully, I will have written or be writing a book, too, as it has been an idle dream since I was a teenager, or maybe it is just the pressure of coming from a literary family.

What’s the chief enemy of creativity?

Health. I spent two times two years stifled by tendonitis, as it robbed me of my ability to create and play. But it also led to me moving to a more healthy analogue workflow, which is partly what I became known for.

You couldn’t live without…

Sparing my family and books. I read an hour to two every night and morning; it defragments my brain.