Interview by Daniela Silva

Self-taught artist John A. Peralta has a whose unconventional sculpture style that combines mechanical objects and high-tech materials to create complex representations that are incredible to the eye. His understanding of what is known as the exploded diagram in engineering terms is genuinely original and reveals his exceptional imagination, technological knowledge, and inventiveness. One of his earliest memories is of him with his brother and their red wagon through the neighbourhood, going door to door, collecting broken electronic devices, opening them to understand what made them work, whatever they could get their hands on.

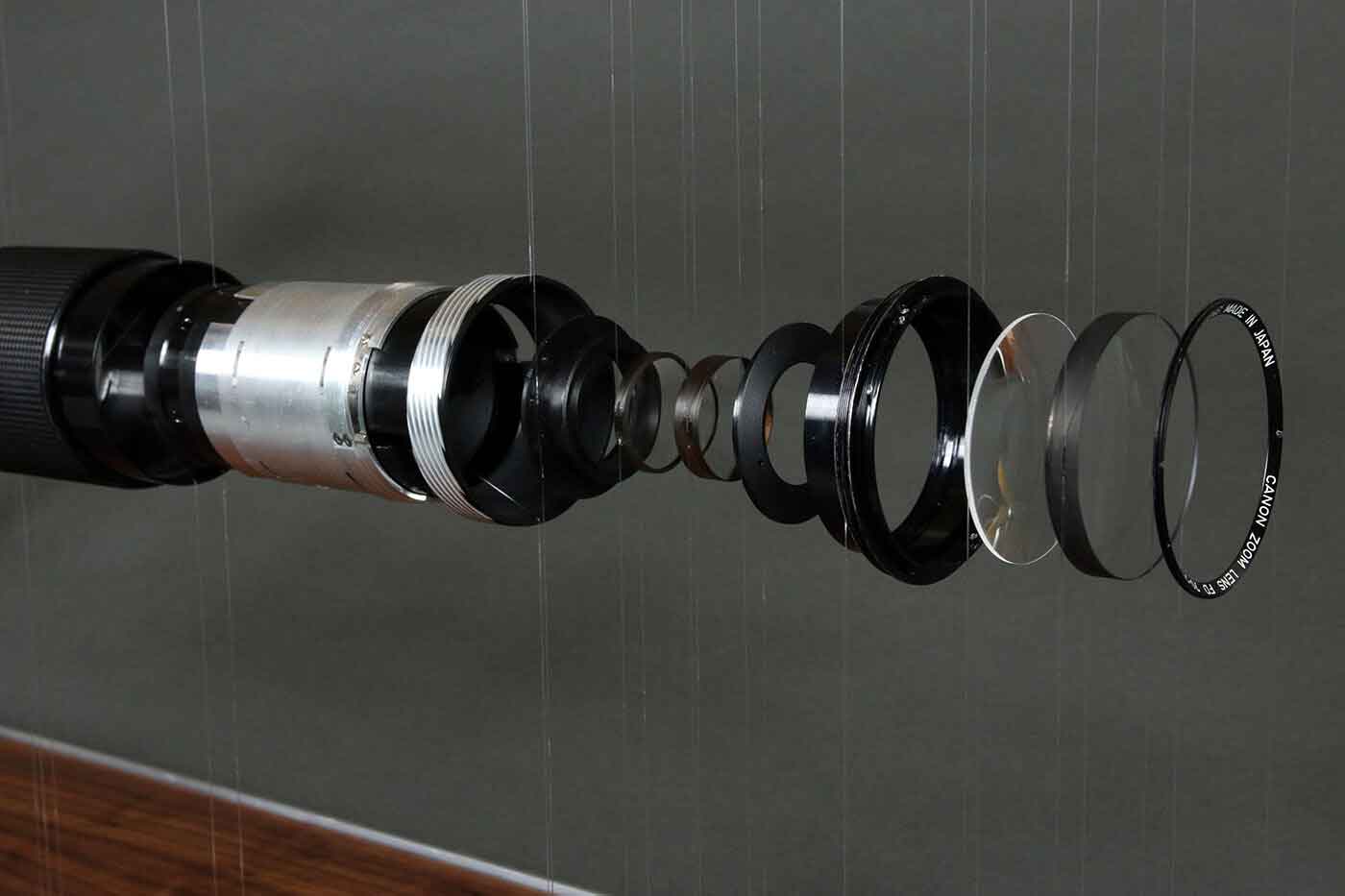

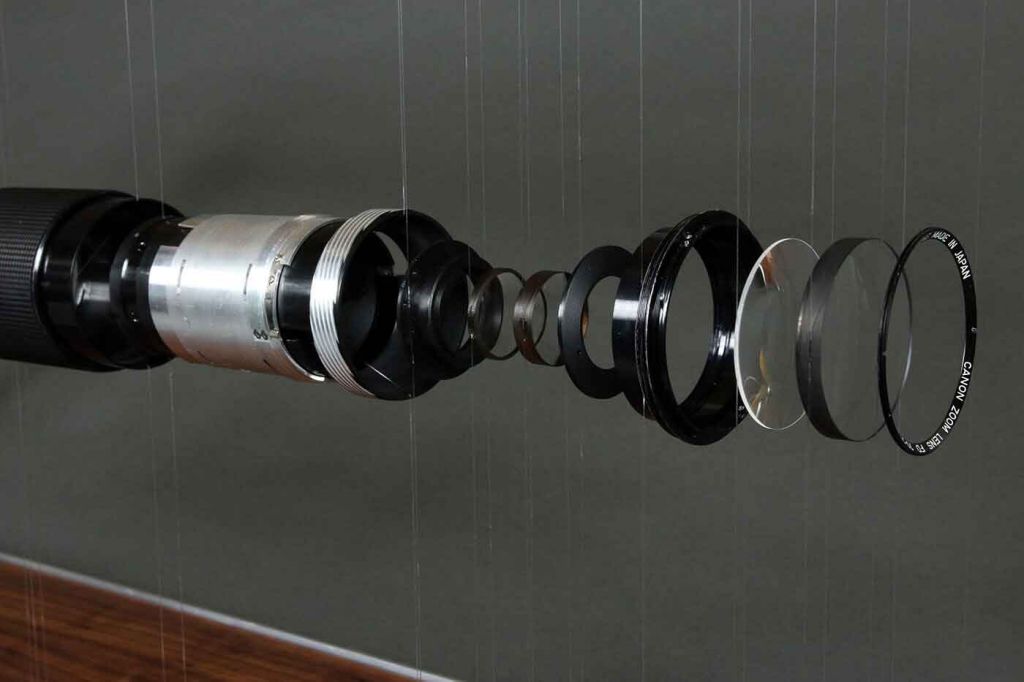

By organising and suspending components of objects like sewing machines, typewriters, and old film projectors, Peralta creates a sculptural ode to some of our most historical innovations. He hangs each pin, roller, and lightbulb side-by-side in specially created lightboxes in his “Mechanisms,” making three-dimensional diagrams that illuminate each machine’s inner workings.

Peralta’s sculptures strip down the most “iconic apparatus” of the 20th century, offering a rare glimpse at the simplicity before the Digital Revolution. In such areas as design, communication, and entertainment, Peralta dissects his peculiar machines. He outlines that he was inspired by their fragile beauty of them and envisioned a three-dimensional version with a real object. Peralta established techniques for suspension using just a ruler and basic methods that still uses today to expose the inner workings of these modest mechanical artifacts.

His most recent work, Music City Ensemble, features a 12-piece ensemble of country music instruments, a major art installation project for the Virgin Hotels. A commission to create the centerpiece of the hotel with a major art installation in the lobby, floating weightlessly from the ceiling in his signature engineering finesse, welcoming guests into the hotel. The installation is meant to be a cultural landmark that offers nuanced perspectives on public art, country music, and Americana.

Peralta has no formal instruction in the arts, and he did not find his artistic voice until his thirties. Still, he is regarded internationally for his technical prowess in creating suspended, exploded sculptures that investigate and pay homage to mechanical technologies and release the memories held inside.

The inspiration for your work “Mechanations series” came from an exploded diagram of a bicycle on the back of a magazine you came across in 2005. Do you still hold that same fascination that inspired you then? How has your work evolved since then?

Yes. In fact, my fascination with mechanical objects has only intensified as the variety of pieces with which I’ve worked has expanded. My interest in them has also evolved. Working so closely with these old machines – seeing the wear patterns, grime, and dust that have accumulated over the decades and even centuries – feels like I’ve been given a private window into the lives of the people who once owned them.

You expose the inner workings of mechanical objects, and the delicate way you expose each piece unveils a complex core of the machines. What are the criteria you consider when choosing the objects you present?

First, I look for objects that are interesting to me personally. I’m drawn to mechanical complexity and elegant design. I also look for pieces with which the average person might have a personal connection; think of your father’s pocket watch or your grandmother’s Singer sewing machine. I’m looking for that deep emotional connection with the ethereal that stirs up long-forgotten memories in the viewer.

Is there any object that you’ve always had an interest in showing in your work and, for some reason, still couldn’t make it?

My original concept for the Virgin Hotel in Nashville was for an exploded grand piano. It was to be suspended upside down from the thirty-foot-high ceiling in the atrium lounge. Later, the decision was made to move it to the hotel lobby entrance, but we couldn’t work it out with space constraints. I still hope to create the grand piano sculpture for a future client. I also have ideas for a full-size fighter jet in exploded view.

On your current installation Music City Ensemble, what is the intellectual process behind it? Why did you choose this artwork for Virgin Hotel?

As I mentioned above, my original design for Virgin was for an inverted grand piano. But being in Nashville, a country music ensemble felt more appropriate. I wanted guests to feel like they were immersed in the musical culture and history of the city from the moment they walked through the doors. I wanted to convey a sense of massive scale with the instruments exploding downward toward the viewer as if frozen at the very split second of coming apart. Finally, I wanted to show off the craftsmanship of each instrument since many people are unaware of how they are constructed.

How do you understand the role of art in public spaces?

I think this is a hard question. Art is so subjective. It seems to me that so much of it fails at its primary purpose. Sometimes it’s too overt: just because you make it gargantuan doesn’t make it good art. Or it’s so esoteric as to insult the intelligence of the general public. This might sound like heresy, but I personally think some of the best public art is commissioned by businesses, as they tend to have clear objectives for it. It’s also been my experience that they usually give the artist a very free hand in the process.

In the early 1920s, the Cubism style helped physicist Niels Bohr determine quantum theory when he compared the behaviour of electrons with Cubist paintings. But, in your view, what is the biggest contribution of science to the arts?

I suppose I don’t draw a distinction between the two. And that’s not because of the style of my art (I have many other artistic interests than working with machines). I tend to see the science in all art and all science (including engineering) as art.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Having spent many years in the worlds of business and academia, the most loathsome label for me has always been that of “team player”. When I think of the periods in my life when I’ve felt the least creative, they’ve tended to be when I was under the most pressure to meet the expectations of other people.

You couldn’t live without…

The freedom to explore, invent, and create.