Interview by Jack Apollo George

Quantum physics is a little bit weird, a little bit spooky. In the 20th century, it fundamentally challenged our aeons-evolved intuitions about the physical world, but it didn’t massively affect our material reality. It only really mattered at the microscopic level. When I put a cat in a box, I’m still pretty confident it will still be there when I opened the box. But when quantum mechanics are applied to technology, the output could become truly transformative.

Whereas many contemporary artists are using scientific innovations to propel and inform their future-gazing projects, Libby Heaney really has the background to tackle the most complex of technical problems in a way that makes these accessible to the wider public. This is because Libby Heaney is a scientist. An expert in quantum physics, she holds an MSc in Physics from Imperial College London and a DPhil in Quantum Information Science from the University of Leeds.

After retraining at Central Saint Martins, her creative, multidisciplinary confrontations of speculative art and quantum physics have captivated the minds and audiences both at home and internationally. Her creative work has employed deep learning, virtual reality and natural language processing to confront themes as varied as online dating, political rhetoric and national identity. However, she breaks ranks with most other artists working on the technological frontline by seeing artificial intelligence as nothing more than a very powerful tool.

Two of her latest works using artificial intelligence and sound are Oh Brian and Euro(re)vision. Oh Brian is a moving image artwork, where artificial intelligence was used to create a so-called deep-faked version of East 17’s Brian Harvey performing his classic song ‘It’s Alright’, and in Euro(re)vision Heaney explores the relationships between artificial intelligence, politics and pop culture.

In her view, the real transformation will come through another emerging technology that she specialises in working with quantum computing. Quantum computing harnesses the power of quantum physics to solve problems that would be too complex or time-consuming for classical computers to confront. By allowing for a third, ambivalent state to be added to the 0-1 binary, quantum computers’ qubits can perform far more powerful processing tasks.

To date, quantum computing has been successfully applied to fields as diverse as protein modelling and financial risk mitigation. However, its potential power has barely been tackled in the creative sphere. Libby Heaney’s combination of erudition and curiosity allows her to earnestly and skillfully explore this key challenge of our age.

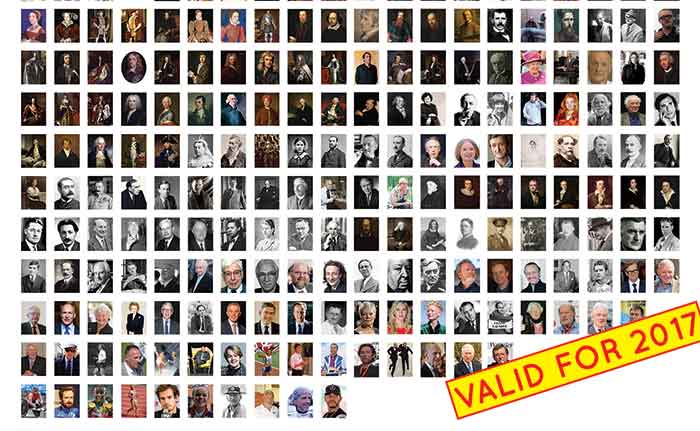

Right: Visual research for biases in the UK citizenship test

For those that are not familiar with your works, could you tell us more about your background and inspirations?

Since 2013, I have combined my critical fine art training with my background in science and technology to creatively explore the impacts of new technology, particularly AI, VR and quantum computing (QC). To do this, I typically make participatory or time-based artworks, usually with some sort of digital or quantum technology. These artworks tend to blur and undo seemingly established categories and meanings, suggesting new possibilities and enabling the often-slippery process of seeing the world and ourselves anew.

Before this, I gained a PhD in quantum information science and spent 5 years as a post-doc working in the area. During that time, I was very concerned about the lack of critical discourse within the subject area. No one was considering what these new technologies would do to the world except for being able to speed up certain computations by a staggering amount.

But what would all this mean? Art and design enables people to understand more viscerally the social, political or ethical effects of technologies, so with this in mind, I retrained as an artist, in part, to be able to question technology more widely and propose alternative futures. When investigating what any technology can and can’t do through art, I often turn to concepts from quantum physics as a way of understanding the pluralities and entanglements between technology, the world and ourselves.

For instance, in quantum computing, the notion of entanglement is fundamental. There, it describes two or more delocalised particles that become inseparable and share information and affect each other even if they are really far apart. I find this a very useful concept to draw on and push against when understanding other technological systems and their effect on society and individuals.

Besides drawing on aspects of quantum science in my artistic practice, I am also inspired by many fine artists working across different media. My favourite artist is Laure Prouvost, whose work is really different to mine at first glance. She is a video artist – making sensuous films and also very tactile installations and sculpture.

In contrast, I work with recent technology, often in participatory installations or online on screens. But I am really intrigued and activated by how she constructs meaning in her work and how she combines language with (moving) image and objects on the screen and in space. Her pieces are often absurd and nonsensical, and I try to understand what that humour brings.

Prouvost’s works are often held in my mind as I incorporate playful elements in my pieces and experiment with (de)constructing meaning with various technologies. I managed to interview Prouvost for my MA dissertation and subsequently argued that her piece The Artist 2013 is like a quantum system, where meanings are delocalised and in constant flux much like quantum information in a quantum computer. I recently cycled from London to her mid-career retrospective in Antwerp. I cried after I saw the show because I felt so moved by her works.

You are being part of Sónar+D 2019. Could you tell us a bit more about your participation in this year’s edition?

At Sonar+D this year, I’ll be on a panel about quantum computing and specifically talking about quantum computing, art and creativity. Drawing on my artworks and also on my teaching and research from the Royal College of Art, I’ll start by reflecting on how the machines of a given era, like the steam engine or, more recently, digital information systems, affect how we interpret and act in the world.

In the age of the steam engine, the world and ourselves were viewed as giant machines. Now that has changed. In our current information age, people see the world and ourselves as computers. These Western world views have also been reflected many times through Western art.

Using this as a starting point, I will then suggest that as quantum technologies, like quantum computing, move beyond our current proof of principle/error-prone stage and infiltrate into various daily applications, such as a future quantum internet or quantum simulators, then perhaps the western world view might start to shift from computational to quantum. What might this quantum worldview look like? And what type of art will be made in response to this?

Quantum physical concepts describe a dynamic and performative universe where human and non-human identities are made plural, where structures and categories ebb and flow based on their entanglements and where time is nonlinear. Quantum physicist and feminist theorist Karen Barad describes a quantum agential reality where such entanglements suggest responsibility for how we act in the world. This notion of human and non-human responsibility is very important, given the impending climate catastrophe and growing inequalities.

I will also speak about future quantum images – i.e. those images produced by a quantum computer. Digital images have shifted our ideas of what constitutes reality. In the future, how will quantum images impact the way we see and understand the world? And how will art change as a result? For instance, in quantum computing, it is impossible to copy unknown quantum information due to the laws of physics. This is a really strange concept for us to imagine because we are so used to being able to share and access digital music files or email attachments even if we do not know their contents.

In the future, quantum information systems will change this. Image sharing might stop or at least change its form, and art may depart even further from copying and reproduction. What will an era of quantum images mean for the West’s 24-hour news stream and social media services? It’s very difficult to answer these questions at this stage, but it is important to start talking and speculating about the impacts of these technologies before they fully emerge. Because quantum technologies’ impact on the world will likely be larger than the internet’s impact.

AI is transforming society, and the creative application of AI opens new possibilities in artistic creation. You’ve been using AI in your pieces to narrate your artistic ideas. What has this media contributed to your artistic practice?

I’m really interested in how AI can be used to disrupt existing categories and cultural and historical biases rather than entrench them as it does now. Currently, decisions made by machine learning reinforce prejudices and other forms of discrimination since the decisions are based on data from the very world where these prejudices are held.

There has been a lot of discussion about how machine learning data sets are biased because they are more able to identify white people than people of colour accurately. However, simply adding more faces of colour to a data set will not eliminate all bias. Even though the machine learning algorithm will equally recognise all people, real-world decision-making will still be biased.

Bias in datasets and bias in decision-making are two different things. In the US, black men are more likely to be identified as criminals than white people for historical and socio-political reasons (the documentary 13th discusses this in depth). An AI trained on historical data of criminal profiles will, therefore, also identify disproportionate amounts of black men as criminals.

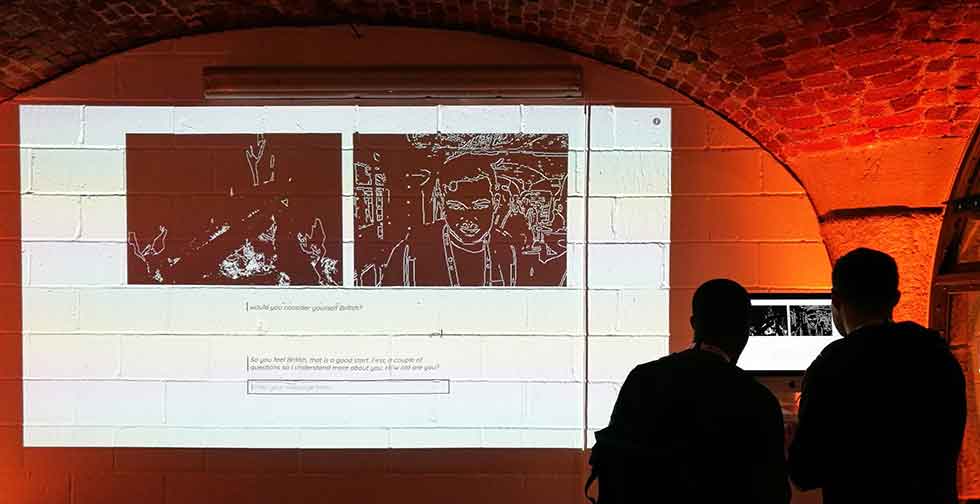

AI decision-making, therefore, fixes and cements historical and cultural biases. Where is the space for change and new possibilities? My AI artworks explore this space. They raise new questions and propose alternatives. My recent works, such as Britbot and Euro(re)vision respond to these questions. Britbot is a voice and a text-activated chatbot that spoke to people about the concept of Britishness and learned from what they said.

It was trained initially on the UK government’s citizenship test, which is a largely white male-privileged version of British history and culture. Britbot was, therefore, deliberately designed to be biased and not representative of multi-cultural, LGBTQ, disabled, poor, average Britain today.

Because Britbot learned from the people spoke it spoke to, it became a wider and, more importantly, an ever-changing representation of Britain in 2018/2019. Interactions with Britbot were very surreal and were often reported to encourage people to re-think the topics being discussed.

My artwork Euro(re)vision took this further. I deliberately deconstructed current political rhetoric from the House of Commons and the Deutsche Bundestag using a character-level recurrent neural network trained badly on this data. This resulted in a type of Dada poetry, swerving between sense and nonsense.

I then performed as Theresa May and Angela Merkel, employing AI deep fake face swap to make myself appear as these politicians in the resulting video.

However, the work wasn’t just about problematizing machine learning and historical and cultural biases. It wasn’t just about the nihilistic destruction of meaning, rendering nothing possible. Rather towards the end of the piece, the English and German languages merge to form a new machine learning-generated hybrid language, proposing an alternative future – a future beyond national borders and traditional politics.

Do you see AI more as a tool or a creator?

For me, AI is definitely a tool. It’s just very complex statistics. If we called art made by AI creative statistics, I think the myths around AI being a co-creator will disappear. This will happen when Adobe AI is released.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

Red wine and sunshine.

You couldn’t live without…

My studio. It’s my little sanctuary, and being in there working away, makes me really happy. My studio and also cake. I do love cake.