Interview by Lucy de Lotbiniere

Manuela Moscoso is an Ecuadorian artist and curator whose current work asks us to question the fluidity and permeability of our bodies. Through her curatorial work, Moscoso emphasizes the importance of understanding ourselves—and our bodies—as sensitive to each other and our surroundings. Inspired by form and process, Moscoso focuses on the depiction of embodiment, interaction, and connection.

Until 2018, Moscoso was the Senior Curator at Tamayo Museum in Mexico City. In 2018, Manuela Moscoso and Andrés Valtierra curated Machine Visions, an exhibition of Trevor Paglen’s work over the last two decades. The vision for the show centered around Paglen’s interest in the digital manipulation of images. His fascination with surveillance imaging, whether produced by the military or police, is linked to the human subject. We interact with technology if we see it or it sees us. As technologies are increasingly able to capture images on their own, Machine Visions interrogates who they watch and what they are trained to look for.

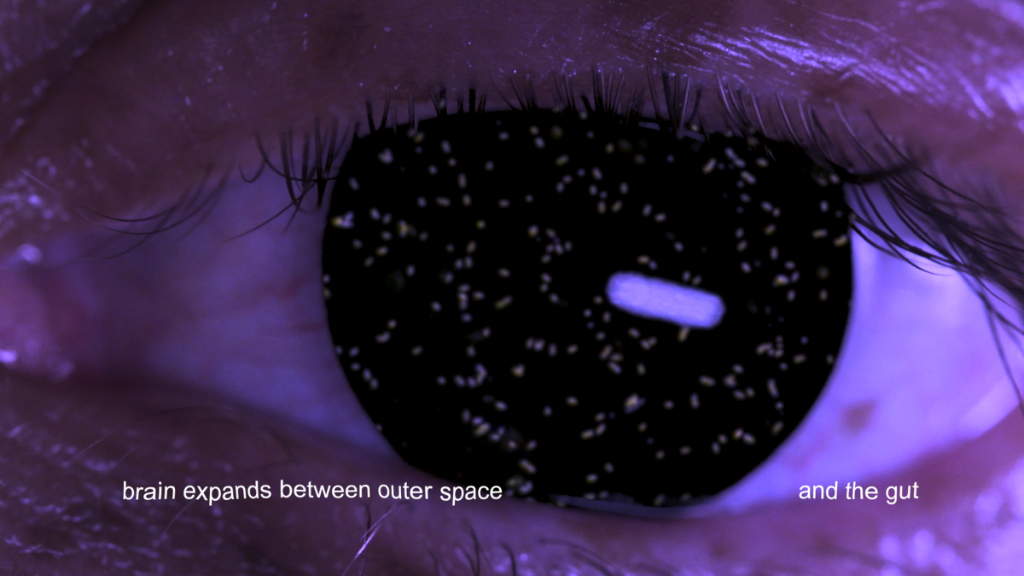

Moscoso is the curator for the Liverpool Biennial 2021, The Stomach and The Port. Liverpool is home to one of the largest and busiest ports in the UK. Its rich history as a global point of connection has undeniably influenced the development of trade and exchange. Moscoso explains that this influence has shaped our understanding of the modern world and has led to our universal understanding of “human” as “Eurocentric man.” By asking us to re-engage with our understanding of the “body,” the work in this show relies on non-Western ways of thinking about the human.

By breaking our expectations and preconceptions of ourselves and our bodies, we can begin to unlearn what we think we know about the human body. To Moscoso and the contributing artists, the human body is absorbent, fluid, and sensitive to its surroundings.

This edition of the Liverpool Biennial embraces ideas of the stomach, porosity, and kin. The stomach behaves as a filter between the external and internal, an organ engaging with your body at the collective level. The porosity of the skin forces us to rethink the edges of our body, allowing us to reimagine where we begin and end. And similarly, the idea of kin leaves us feeling interconnected and inseparable.

The artists featured in The Stomach and The Port engage with the current definition of our bodies and their histories. A series of sculptures by Norwegian artist Ane Graff are featured in the Biennial. Her work is informed by a feminist new materialism, where human beings are part of a larger, intertwined network, and the body is a meeting place for these different realities to interact. The sculptures are inspired by research that links environmental risk factors to mental well-being. The sculptures are filled with “pollutants” and become bodies themselves: meeting places for material and narrative to mix.

This edition of the Liverpool Biennial also sees work by Rashid Johnson, who lives and works in New York, US. Moscoso has worked with Johnson before, whose work explores themes of personal narrative, cultural identity, and materiality. Johnson’s large-scale public sculpture will be situated at Canning Dock Quayside, an early location for the transatlantic slave trade.

The large totem bronze structure takes inspiration from a series of Johnson’s drawings, Anxious Men, which bring about a sense of collective anxiety. The sculpture is furnished with plants that grow from within the sculpture. The yucca and cacti plants were chosen for their endurance in harsh weather conditions and represented the resilience of Black people who are racially discriminated against today.

For our audience that is not familiar with your work, could you tell us a bit about your background and inspirations and how these relate to your current practice?

I was born in Colombia and grew up in Ecuador in the late 1970s. My background is as an artist, and has deeply influenced the way I think as a curator. I also arrived at the world of curating through being the co-founder – with artist Patricia Esquivias — of an artist-run space called los29enchufes in the early 2000s in Madrid. Since collaboration is fundamental to my professional practice. I frame my vision of curating into the notion of the curatorial, a practice that goes beyond the making of exhibitions and emerges as methods for creating, mediating, relating and reflecting artmaking, experience and knowledge.

I study the process of art-making and its effect on the world. When looking into practices, I sketch out social and affective systems, cultural understandings and human conditions since producing never stands alone but in a relationship to others. I understand the practice of curating as a form of continuous learning from and with artists that is never the same and is unconventional. Every experience nurtures my curiosity and desire to challenge the status quo, fosters speculative thinking and brews my imagination.

This is why I often define myself as a curator of practices rather than objects since understanding how people research, create, think, produce, relate and disseminate work and ideas enables me to constitute visible and temporal contact zones in the (expanded) form of exhibitions – for encounters of similes, contradictions and conflicts.

This year’s theme is The Stomach and the Port; what has been the intellectual process behind it? Can you outline any particular approach being taken in the development of Liverpool Biennial 2021?

I was invited in July 2018, and this process started with a desire to continue thinking about forms of decolonising thought processes and artistic practices. The biennial explicitly explores notions of the body, drawing from non-Western ways of thinking. The artists and thinkers gathered in this edition challenge an individual’s understanding as an autonomous, self-sufficient entity. Instead, the body is seen as a fluid organism co-dependent on others that is continuously shaped by and shaping its environment.

It would initially seem a straightforward notion when our answers are drawn from a foundation of knowledge steeped historically in Western reference and frame of thought. However, over centuries, a social understanding of what a human is has assumed a particular body: the one of a “man”. A “man” is not a neutral designation.

Among many intellectual inclusions and constantly in conversation with artistic practices, two important thinkers from an academic perspective are Eduardo Viveiros de Castro and Sylvia Wynters. Vivieros de Castro has been focused on the study of decolonial thinking with the learnings from Amerindian epistemologies, thinking on the body beyond its concrete physical boundaries where the possibility of being human extends to animals, plants and other beings.

On the other hand, Sylvia Wynter explains how Western man came to be considered the epitome of humanity through robust knowledge systems and origin stories that explain who and what we are. Wynter then attempts to deconstruct the human’s biocentric premise as a purely natural organism in Western modernity. She explores a different possibility of reconceptualising humans as hybrid beings to blackness, the Caribbean and migratory politics.

Having the ground prepared, and simultaneously, my practicewhichInstead, the body is consists of gathering different practices that consider these questions necessary. Together, in the form of an exhibition, a curatorial grammar is constructed between all of us.

Any standout artists or works to enlighten us to? Could you advance us a little bit on what is to come?

One of the three suggested entry points to “The Stomach and the Port” is porosity. To accept porosity is to accept a form of exchange and the possibility of transformation. When we recognise our bodies as porous, we also reject humans’ ideas as exceptional and separate from nature.

Jorge Menna Barreto’s “Weed Mural” (2021) documents wild edible weeds found in Liverpool that are not cultivated but thrive naturally in local conditions. They are presented as our associates rather than a product. Through eating weeds, for instance, we can learn about the place we inhabit and read not necessarily with our brain but with our stomach, and our stomach is the sculptural tool that transforms the landscape.

Digestion and gut intelligence are also present in the work of Ane Graff. She is interested in researching how the bacteria that inhabit the human gut become part of who we are, affecting our personalities and mental and physical well-being. Her practice is concerned with how a body is multiple beings intertwined, not a finite being, but a porous matter that allows the environment in which it resides to define it.

The idea of the body as a multispecies location is also present in the practice of Jenna Sutela. We are presenting, for instance, the sound work “nnother” (2021), made in collaboration with writer Elvia Wilk. All about symbiosis, and the topic of gestation, presenting a conversation between imaginary organisms with both organic and synthetic attributes, one of whom lives inside the other.

And thinking on motherhood, we present a body of work by Camille Henrot exploring the trope of mother and child and the alienation of the body through society’s eyes, seeing the body as a series of actions and excesses. Graff positions the body as part of a more extensive system, a meeting place for narratives, materials and influential external factors.

In times of social and climate crisis, complicated relationships with technology and political strain, what role does art play today in describing contemporary society?

I don’t think that art plays a role in describing, as describing would give a viewpoint, and we would have to ask how that viewpoint was constructed and how it emerged. I would say that art plays a role in exploring, from an interdisciplinary practice, the complexity of contemporary society. It creates associations, research, predictions, fictions and even possibilities of what it means to inhabit the world in particular conditions. Not one world but many worlds.

How do you envision the future when the world is back to what is being called the ‘new normal’ or the ‘new normality’ after the pandemic? Do you think the online exhibitions and events we are experiencing these days will be continued?

I hope the pandemic will produce tectonic movements in our understanding of ourselves as autonomous and individuals, growing a sense of how intertwined we are and how much we are co-dependent. This is what I hope; then I think there will be many futures. There are many presents of how the pandemic circulates and affects people depending on where one is geographically and the individuals’ racial, social and economic contexts.

I think there is no substitution, one for the other; online is a different format. We will have more online content, which will become another way to make things happen. Many of the exhibitions we see have been prepared in the past, so we are still looking to pre-pandemic forms of making something public. We are still in the past if you like. In terms of the future, we will adapt and consider the new conditions essential when producing shows, art, events, etc. I guess art will change too; I do not know in which direction. We do not have to predict as much as we need to listen.

Technology is becoming increasingly embedded in the arts. Do you have any predictions, expectations, or fears about this deepening relationship?

Not really. There has always been correspondence between technology and the arts, which will continue in different and unexpected ways.

What would be your biggest curating extravaganza?

The extravaganza would be able to produce all the performances that we had planned for the Biennial. Unfortunately, many of them had to be adapted, and some cannot happen due to the current social distanced world.

You couldn’t live without…

Love.