Interview by Leoni Fischer

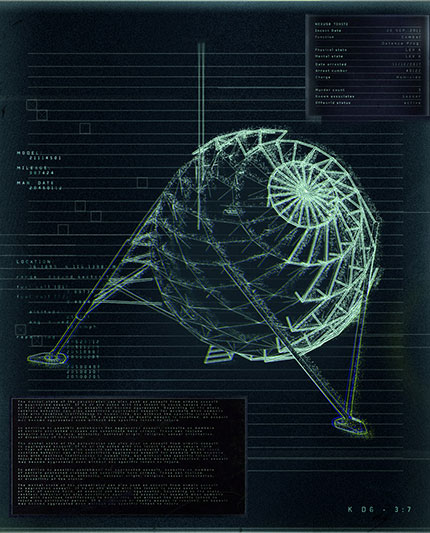

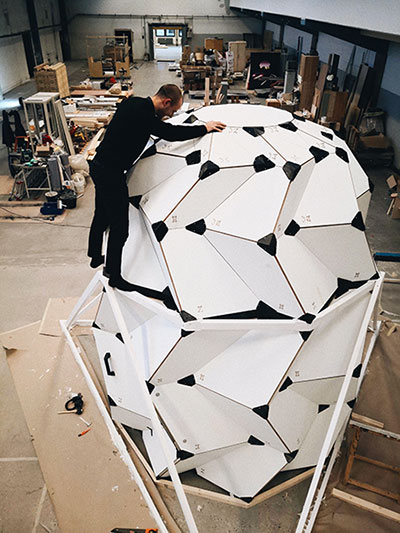

Two figures are walking through a vast scenery. Diffuse light sheds a gleam over the featureless territory. Packed up inside puffy white suits their walk looks uneasy but determined. Lumberingly, they set one heavy foot in front of the other towards a three-legged structure that supports a folded capsule. This geometric formation, with its’ antenna sticking out from the top, curiously resembles a dark-shaded pineapple.

Karl-Johan Sørensen and Sebastian Aristotelis, the young and ambitious duo behind SAGA Space Architects, are the protagonists of this project. In September, they will leave their Copenhagen home base to set out on a mission that explores the potential of human settlements on the moon. Unable to fly to space in a rocket ship, they will travel to the moon-like wastelands of arctic Greenland to test their high-performance habitat.

Designed as a closed system with solar panels, waste storage, an algae reactor, circadian light panels and a plant wall, the team aims to go beyond the most basic necessities for survival to create a stimulating housing environment. Captivated in the isolation of the habitat for three months, they are looking to bring back empirical knowledge that will shift perspectives on space colonisation and the future of “earthly architecture” altogether.

Looking at the LUNARK habitat instantly evokes a wide range of associations stretching from Buckminster Fuller-esque geodesic techno-utopia to the capsule hotels of contemporary Japan. Standing on three wiry legs to keep the self-folding capsule hovering above the ground, the habitat looks like it could start walking any second. It embodies the ideal of extreme mobility.

In recent years accelerating housing crisis and ever-denser cities have led to a revival of the Tiny House movement that had started with pioneers such as Sarah Susanna and Lloyd Khan in the 90s. But instead of fleeing the city towards a self-determined life in nature, this habitat is designed to go much further. Many have claimed that abandoning planet Earth will eventually become inevitable for humanity as a way to persist and grow.

In fact, looking at Won Kim’s famous documentary photography of urban dwellers permanently staying in the coffin-like chambers of a backpackers’ guesthouse in Tokyo renders such conclusions rather plausible. Undeniably, astronauts, rocket ships and space stations have always been fueling imagination and fantasy. Inevitably though, this fascination comes with the dark shadow of the Arms Race in Outer Space.

One can only imagine the countless ethical and political challenges arising from the residential colonization of foreign planets. On the other hand, the sterile rocky nothingness of the moon awaiting future settlers holds the tempting promise for society to hit the reset button. Coming generations will decide which path to take.

Maybe one could consider the LUNARK Mission an expedition to the halfway mark. Carried out somewhat betwixt and between Utopia and Dystopia, Earth and Space, Art and Technology, SAGA’s mission radically challenges the foundations of today’s building practice while charmingly envisioning designs for the inhabitable planet Earth.

You are an architecture studio working with Space Architecture. For our audience that is not familiar with your work, could you tell us a bit about your background, interests and inspirations?

We were always quite interested in space and fascinated by space explorations, but with our background in Architecture, we never thought we had the right skills to contribute. Talking about space architecture and foreseeing that space will be more privatised, with an increasing number of people going there for a more extended period, it became clear that there might be more to do than just engineering and physics when going to outer space.

Ultimately, we will always send humans to the moon, and humans don’t only require an environment that supports basic necessities for survival but want to feel comfortable, protected, happy and stimulated. Initially, we just started with that idea, tried out different things, did some competitions, and it turned out that our designs had some potential. We then went to the International Space University, where we presented our ideas to a broad audience of engineers and scientists in the space industry. This was received in a way that made us believe that architecture and the arts have something to add.

For your LUNARK Project, you are working on a foldable habitat for life on the moon. Could you tell us more about this project?

Everything started with our interest in Space Architecture, but nothing is built on the moon yet. How do you design for a place you haven’t visited and where people haven’t been for 50 years? Our idea is to create a simulated moon mission in a place on Earth that comes closest to the environment on the moon. This is why which is why the mission will take place in Greenland. Right now, we are designing a prototype habitat that solves some technical challenges of living in space. For example, it is small in transport because it deploys to become bigger. We are also incorporating our ideas on environmental psychology and demonstrating that in the interiors of the habitat. We are building a proof of concept to show it to people – in science; this is called a technology demonstrator.

And because it is our mission, we will go to Greenland ourselves because, as architects, it is vital to know about the challenges and the place you are designing for and experience it. When it is so foreign, I don’t think there is any way of adequately putting yourself in the astronauts’ shoes without actually simulating it. For us, it’s also a way to gain experience to design better homes for future innovation. In addition to that, it’s also an opportunity for researchers, especially psychologists, to test some of their hypotheses on long-term isolation, group dynamics and sensory deprivation.

Doing a few studies about what it is like to be trapped in a place like this is a rare opportunity for them because the only other places you would find test subjects like that would be in prisons or polar stations. But the conditions there would still be quite different. Hopefully, at the end of the mission, it will show some value that can be used for new architecture in the future.

One of the first theoretical works published on rocket-powered space travel was by K. Tsiolkovsky in 1903, who believed human space occupation was the inevitable path for our species. How probable would you render that scenario?

I think going to space is inevitable. If you put it into perspective, there are only two scenarios in millions of years from now. On the one hand, if we continue to explore and expand as humans have always done it (and I am not saying if it’s good or bad ), we might have a chance to stay alive and develop as a species. Or we decide to stay on planet Earth, but eventually, something will happen, an asteroid or a human-created disaster like global warming or a nuclear war. Of course, it’s a bit abstract in relation to our daily life, but I agree with him. Tsiolkovsky once said that Earth is the cradle of humanity, but you shouldn’t stay in the cradle, and I would agree with that.

Where does your motivation to work on a livable future on the moon come from?

I think it’s such an interesting problem to work with creatively. Architecture on Earth has a long history; we have built things for about ten 10.000 years, and on Earth, everything we build is defined by the parameters of the Earth, like gravity or weather. But going to the moon changes all those fundamental things about design. On Earth, we built roofs to shield us from rain, but a roof on the moon doesn’t make sense because it doesn’t rain there.

However, there is still cosmic radiation which we would have to shield ourselves from, but this solution probably would not look like a regular roof as we know it. On Earth, we have an atmosphere with a specific pressure which we don’t have on the moon, so you would have to create an ecosystem within the building – it would have to be a closed environment.

I am not so interested in Space Architecture because I want to be an astronaut but rather than the fact that the problem is so strange and fascinating, and people are going to do it anyway, so we might as well do it right. It’s rare to get the opportunity to define the fundamental standards of design, and that’s one of my motivations.

The field of Space Architecture derives from the time of the cold war Space Race. What’s your political and ethical stance towards the human colonisation of other planets?

There are right and wrong ways of colonising other planets. It’s not so much what we do to the planet itself but more what we do to each other as we go to these planets and what it means for a nation to acquire property on the moon, if that is possible. Colonising is also a weird word because it brings up ideas about going to an untouched land with people and culture and claiming those for yourself. But if you are going into space, you are going to a barren rock.

I don’t think it’s a colonisation scenario apart from the fact that you are establishing a colony and making a place for humans to live. Suppose it’s done right with a non-military purpose. In that case, if there is collaboration and without wanting to gain an economic or political advantage like it was in the cold war, I think it would be entirely ethical and something for humans to aspire to do. It’s idealistic, but I see it as a chance to establish a clean state in a way. You are going to a place that doesn’t have any history and no predefined idea of how it should be – but it would have to be done right.

Due to the extreme environment in the Arctic, you are planning your habitat as a closed ecological system. What personal lessons do you expect from living inside that system during your mission? What will you miss the most, and what temptations will be hardest to resist?

I don’t know what to expect, and I don’t really want to expect anything right now. We are trying to establish the mission as an experiment where we don’t know how it will feel, but honestly, I expect it to be a very boring three months. We might be in an extreme place, and it might be isolated and cold, but we will be inside our little capsule anyway. It’s not an extreme mission because of the danger but because of the sheer boredom, which is why I hope to find creative ways to relieve myself.

I hope that the systems that we integrated, like light panels simulating the daylight, the plant wall or algae reactors, will prove to be helpful in the psychological aspect, but it’s an uncertain outcome. Generally, I think I will miss people the most. The fundamental problem is that we are social beings and can’t bring all the people we love on the mission. It may also be hard not to go outside without our space helmets, only to feel the fresh air. But we need to stay honest about the mission, and it wouldn’t work to go outside on the moon – so we will not do that in Greenland either.

Let’s take a look at the bigger picture: Do you think your mission could open up new perspectives on earthly challenges like climate change and overpopulation?

I hope our capsule will paint a positive picture of how you can build without being seen as a doomsday scenario. I think building light and mobile using thin, durable materials should also be implemented into how we build on Earth. Those aspects could inspire earthly architecture. Of course, in a grim future, circadian light panels could be helpful for people on Earth as well, but we are hoping that it won’t get to that.

One for the road… What are you unafraid of?

Most people think we will become enemies during the mission because everyone knows that the longer you spend with someone, the more irritating it gets. But I would say that I am unafraid of the mission because humans are doing far crazier things all the time.

In Greenland, every winter, two people are sleeping in a tent on the ice caps, they are part of the military, of course, but they are still people, so in the light of that, our mission seems like a holiday. In the past, people travelled across oceans for years without any way to communicate with the world, and they survived. We have a lot of facilities and support systems, so that makes me very unafraid.