Interview by Jacobo García

For anyone that follows the daily press, it’s easy to fall for the piling news that Russia is consolidating as a global antagonist of democracy. Government threatens minorities and activists every day, and civil and human rights are attacked. Not only that, Russia is pushing its agenda against Western democracies globally, killing dissidents in the UK and influencing elections in Madagascar or USA. In times of turmoil, it’s more important than ever to build bridges with Russian communities, artists and activists.

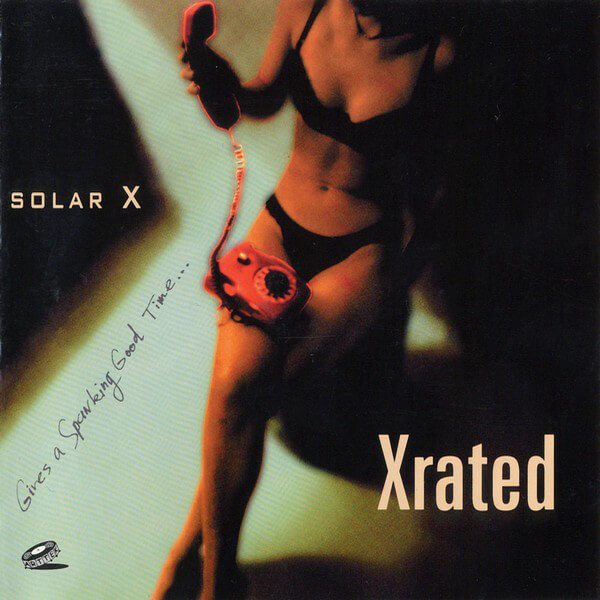

SolarX‘s musical output commences at a moment when Russia could have become a functioning democracy, just a few years after the wall fell. It was a moment of optimism; the country opened to the world after 74 years of communist rule. This spirit of leisure and opportunity reflects on SolarX’s second album: X Rated.

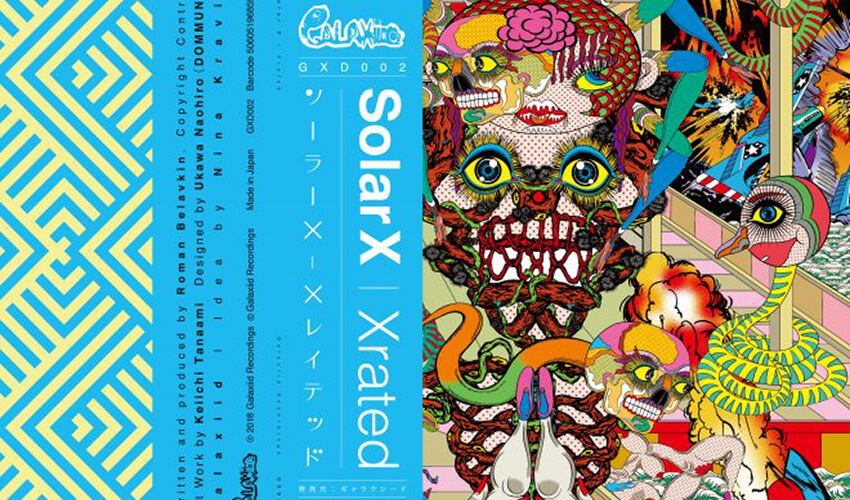

This record, available only on CD or cassette, has been recently rescued and re-released on Nina Kraviz’s Galaxiid, a sub-label of Nina’s main imprint трип focused on ambient and more experimental music. SolarX gained international attention in the 90s at a time when Russia was (quite unfairly) seen as a vacuum for electronic music, exploding in the period of piracy, poverty and freedom following the collapse of the USSR. After a few years, the artist retreated from the music media, pursuing his other career as a lecturer and researcher of AI, information theory and cognitive science. It is widely believed that Russia’s electronic scene was non-existent in the 90s, but this can’t be any further from the truth.

The Soviet Union has a long story regarding electronic sounds that trace back to Leon Theremin, the inventor of the musical instrument of the same name, continuing with a series of synthesizers that have reached cult status in the last 20 years, and of course, the underground, counter-cultural scenes of the 80s and 90s in San Petersburg and Moscow. In this context, X Rated musical outputs feels more connected to what was going on in the rest of Europe at that time.

A welcomed re-release, it flows in unconventional ways: with unstructured tempo changes and tepid, liquid melodies layered over relaxed rhythms. All in all, melodies reign in this elegant set of songs; they provide a beautiful soundtrack for those times of hope and freedom. There are numerous re-editions out in the market, obscure electronic artists being revindicated every week from every corner of the world, but few feel as urgent and relevant as Solar X feels today.

You are an electronic musician and computer science also has a career as a lecturer and researcher of AI, information theory and cognitive science. How and when does the interest in this discipline come about?

My father was a mathematician, and although I did well in maths and geometry at school. Initially, I was not planning to follow my father, and I did not want to be a scientist. I graduated from the Physics Department of Moscow State University (in 1994), but I was very much into sports and music during my student years.

Later, however, I began thinking about music, why it is such a powerful communicator of emotions, and what happens in the brain when you listen to or compose music. I was also experimenting with computer programmes that could assist you in arranging music, rhythms and composition, and it was very clear that although algorithmic composition could be quite interesting, it was not the same as listening to human-made music. There is a difference between Bach and a computer.

I started making enquiries about the potential of doing some research in this area, and I found a response from Frank Ritter, who was a cognitive scientist and AI researcher at the University of Nottingham. And following these discussions and then an application process, I ended up at the University of Nottingham, doing my PhD with Frank, situated between Computer Science and Psychology Departments (who split my scholarship).

My research was not only about neural networks and cognitive science, but it took me back to mathematics, physics, and information theory. I got so incredibly immersed in my research for several years that my music production inevitably slowed down, but I did continue composing and released some new music occasionally. After completing my PhD, I got a post at Middlesex University, which always had a strong AI community, and stayed there enjoying my academic life.

Your music project Solar-X was influenced by art-tech concepts, chaos and complexity, exploring the ways in which our minds can be manipulated by structure. Could you expand on these conceptual ideas and how you explored them with your productions?

I grew up in Moscow during the 1970s and 1980s, and I was influenced by Russian and Soviet culture, which was very futuristic in these communist times, with space exploration being part of everyday life and news. My family, however, was quite dissident, and there was a lot of influence from the West.

I also liked the Russian avant-garde culture of the early 20th century, and I think I intuitively wanted to take elements from all of these influences. For example, in the mid-1990s, when I started our electronic music label Art-Tek Records in Moscow, I was thinking of the label as a kind of community uniting electronic musicians, a kind of “OBERIU” community (“Union of Real Arts”) established by my favourite writer Daniili Khrams.

In fact, sometimes I wanted to make my music a bit like his absurdist stories. For me, it was not about releases and records but more about art and avant-garde, which is what electronic music is. Of course, you need records to capture music, so we released something.

Was the music of Solar-X very defined by the machines you were using in the 90s?

The rave era of the early 1990s did influence us all, but I also used to listen to a lot of classical music, both Western (e.g. Bach) and Eastern (e.g. Chinese opera). I bought several old Soviet analogue synthesisers, which were affordable and made some unique sounds. I combined them with computers and soundcards.

But at the end of the day, it is not that important what instruments you use; it is the melody and the idea that is important. The sound and style are contemporary elements (i.e. fashion) that age and are quickly forgotten if there is no strong melodic component. But if the music touches something deep inside you, then it may exist without contemporary context.

In the last years, Russia seems to be flourishing with electronic and experimental music producers and festivals, but what was the scene back in the day when everything was more secluded? And what do you think has been the driver of this new creativity openness?

I think avant-garde music, and art in general, develop faster when there is political oppression. When Putin came to power, and KGB effectively hijacked the country at the end of 1990, I knew that there would be less freedom, but at the same time, I thought it was good for real underground music (selfish me) because art becomes a form of protest.

You can see this now in Russian rap as well as electronic music. Back in the “free” 1990s, there was a lot of experimentation, but I think music was a bit happier, perhaps less dramatic. This is in contrast to some political and economic chaos of the 1990s in Russia.

In one interview, you mention that during your university Leon Theremin, the inventor of one of the most haunting electronic instruments, was still around. How was having a figure like this in close proximity?

I was a student in the Physics Department, where he was a Distinguished Professor. He was already very old, and I did not take any of his classes, but he was very noticeable at the university. You would recognise him immediately in the corridors or in the canteen. Everybody knew who he was, a living legend. But at the same, he was an illustration of a complete despair situation that Russian science got into due to the economic chaos of the 1990s. There was hyperinflation, and salaries were totally inadequate.

It is during this time that my father decided to accept a job offer from the UK, and there was an exodus of scientists to Western universities. Those who stayed had to rely on grants from people like George Soros because the government completely abandoned them (and the situation has not improved much since then, even despite the “rich” 2000s). So, I remember Leon Theremin sitting alone in the canteen, wearing an old suit and eating pasta. It was very symbolic.

Moving to your academic career, what are your main research interests at the moment?

I would say information. Theory of information, information geometry. And its applications to learning theory, machine learning algorithms, AI, and cognitive science. I think the ability to value information is directly linked to our emotions, and this is what I call “hot cognition” (as opposed to old-school “cold” algorithms).

It is interesting that, mathematically, information theory is very close to thermodynamics, and there is even a temperature parameter there. These processes are universal and play a role not only in cognition but also evolution and life. Recently, I have been collaborating with biologists and found the same laws driving evolutionary processes, such as a mutation in DNA.

This work is theoretical but has a lot of practical potential, for example, in medicine (e.g. development of antibiotic resistance in microbes or evolution of cancer) or in engineering (e.g. using evolutionary algorithms for optimisation).

AI is transforming society, and the creative application of AI is opening new possibilities in artistic creation; how do you think new inventions (machine learning, Google Magenta) are impacting the landscape of art creation (from inception to production)? Do you think AI-generated art is going to change the paradigms of art?

No doubt about it. New technologies will always find their way into new art forms, but I think human artists will remain at the centre anyway. Art is for human consumption. And if artists can benefit from some technologies, they will definitely take advantage of them. For musicians and composers, I think the most interesting area to watch is technologies for people with impaired vision or hearing.

Soon there will be technologies that will listen to brain signals directly and allow us to type text without touching keyboards or screens. I am sure that later these technologies will develop into a possibility to record music or sketch animation directly from your thought process. I think it will be possible within a decade or two.

And why do you think it is relevant to produce art with AI; what are the main relevant conversations in your opinion it sparks?

I am not sure why it would be relevant. AI is just a kind of technology (I am not talking about AI in the big sense of creating an artificial mind, this may not even be possible, we don’t know). There can be lots of different applications of these technologies, from organisation, classification and retrieval to assisting in the creative process.

Of course, perhaps the most common conversation related to this is about AI replacing human, and I think it is completely unfounded. It is the same as we used to worry that machines would replace people. They can replace us at boring or routine jobs giving us more free time to create and enjoy life.

Your chief enemy of creativity?

Following news. You can waste too much time reading or following something that appears important.

You couldn’t live without…

Creating something (music, mathematics, programming).