Interview Silvia Iacovcich

It’s natural for humans to use sound as a main form of connection – communicating involves employing complex linguistic and musical systems, a legacy of a more ancient relationship with sounds. If auditory recognition memory seems to be scientifically considered secondary to the visual one, Stuart Fowkes’ project ‘Cities and Memory’ offers a fascinating alternative to how we can perceive and welcome the world from a refreshing and unexplored perspective: a door to discover how sounds can replace the visual exclusivity to which our consciousness generally relates when processing reality.

Cities and Memory is a distinctive journey, a new mapping system accessing and investigating communities, events, patterns and habits, turning sound into a compass to explore our surroundings. The project – started by Stuart, flying solo – has quickly seen the development during the past five years into a solid global collaborative project; more than 750 different artists have come on board to produce and revisit more than 4000 different sounds, evolving into an ambitious list of sound maps that are spread over 100 countries and territories across the globe.

The soundtracks represent the concept that portraiture and music are not distant worlds, that melodies and sights are well able to evoke emotionally charged memories in different ways. Through the Sound Photography project, photographers and sound artists interact to delve into their relationship between both mediums. Iconic world locations, photojournalistic stories and nature photography are revisited through a different channel into a new nature – sometimes with recordings of people’s voices, electromagnetic fields or historical sound recordings from past lives. The process of creation is essentially without limits.

The main site page introduces us to a map where we can virtually get lost into an extensive number of pins to click on. Each pin represents a specific city and its sound and splits into a ‘city version’ of that same sound and a ‘memory version’ of it. Every field recording in the project has been re-processed and re-imagined by a chosen artist to design an alternative nature through the ‘corruption’ of the melody itself, subjectively recomposed.

It is this receptiveness to personal interpretation that makes this vision more engaging and open to dialogue between different artists – the way sounds move across different locations and dates might seem hard to categorize, evoking a combination of sounds and images we wouldn’t be able to establish through the sole use of sight. Cities and Memory features many different ways of encapsulating space and time through a catalogue of different projects. ‘Future Cities’ examines urban spaces and how the soundscapes of our cities are changing, and the way this transformation is and will impact our lives.

‘Protest and Politics’ remaps the world in correlation of demonstrations and political activism around the world: a fascinating way to collect data and explore our behavioural patterns through the type of environment generated during marches, riots, and protests – it looks like it is consequential for feelings and sounds to become linked, complementary. There are archives of field recordists from protests in Bogotá to the marches for Brexit in the UK, to the protests in Tahir Square in Cairo: minutes of silence, odes to joy, noises from crowds in marching groups. Moments are documented and leave indelible sound traces.

#stayathomesuonds is a specific collection of sound recordings from the worldwide Covid-19 lockdown: the data collected gathers intimate, familiar spaces during self-isolations, idyllic sounds of nature reclaiming the deserted roads, noises from balconies and voices of people trying to reconnect. They unite culturally distant areas of the world, capturing sounds of cities during coronavirus outbreaks. They make the world look not so big anymore, traversing it one sound at a time.

For the audience who is not familiar with your work, could you tell us a bit more about Cities and Memory and its evolution?

The project started around five years ago with a single sound on the map near my home in Oxford, UK, and has expanded since then to more than 100 countries, more than 4,000 sounds and over 750 contributing artists all over the world. Every sound on the map is accompanied by a “memory” version, which is a recomposed, reimagined or remixed version of that sound through which our users can explore the sounds of the world as they are, or explore an alternative, imagined sound world created by the collective imagination of hundreds of artists. Remixing the world, one sound at a time – in short.

The ‘noises’ recorded during the protest project struck me as surprisingly ‘melodic’ – an almost song-like celebration of freedom of speech. Were you surprised yourself by any of the musical features that emerged from these examples of shared human activity? Or were they chosen by design?

I would have to say that I wasn’t surprised to hear so much musicality in the protests when any gathering of humans around a common cause, whether a sports team or a political issue, has always led to song and melody for thousands of years, so the protest songs and music are just part of a long and grand tradition of rallying around sound to express a common cause. What was remarkable was that in the social media age, with songs and chants travelling overnight online, so many of the same songs were heard, for instance, all over the USA when protesting against Trump (and this is reflected by other protests worldwide too).

Through #stayhomesounds, there are a variety of worlds we can explore without being distracted by vision: what is the relation between sound and visual in portraiture in your experience?

Both are about capturing a moment in time and about capturing that moment necessarily subjectively through the choice of framing – “framing” in the case of audio being the choice of what, when and where to record. Sonic portraiture has the advantage, I think, of more immediately being able to place the listener into that time and space, as there’s something more intimate and more immersive in capturing a snapshot of how a place sounds rather than how it looks. In fact, the intersection between sound and image was something we explored deeply in our Sound Photography project.

Are there any relationships between lockdown field recordings that connect culturally distant areas of the world?

Several, actually – the sounds can be divided into a few categories – there are the brand new sounds which we’ve never heard before, for instance, anti-coronavirus songs being broadcast in Senegal or the ringing of bells and applause to celebrate healthcare workers. Then there are the sounds of nature, which are reemerging now, and people are noticing louder bird calls and new forms of wildlife they couldn’t hear before over the sounds of the city.

There are the sounds of deserted spaces – for instance, how to do famous urban tourist attractions like Times Square sound now that they’re empty? And finally, there are the sounds of family and home – how are people passing the time, keeping in touch with loved ones and sharing their stories during this time?

The similarities between some of these sounds in different and distinct parts of the world are striking – in the shared applause for health workers or the re-emergence of nature and birdsong in urban spaces, for instance, or even in the increasing sense of disquiet and even protest at government handling of the crisis in several countries. I feel that the project performs the role of bringing people together and demonstrating how we’re all living through this moment as one global community.

Reimagining sounds present a specific place and time as ‘somewhere else, somewhere new’. How does the selection process work to convey a reimagined recording?

The only criterion applied to a reimagined sound is that it must contain the original sound recording or part of it – whether unprocessed or heavily effected or treated musically, for instance. Beyond that, it’s a free composition, allowing artists to bring to bear all of their experience, talent and memory to that recording – I could give the same recording to 50 artists and get 50 completely different compositions back, which is a fascinating thought in itself. Just as the same place sounds different at different times and on different days, so a reimagined sound of the same place is different for every artist.

The interpretations have varied so wildly – from beautiful pieces of music to more abstract sound artworks, through to reconstructions of the original location using TripAdvisor reviews! But I think my favourites are when the artists engage deeply with the context of the sound – thinking about the place and the moment and allowing that into their composition, or when they truly bring some of their own memories and life experiences to bear on a sound from another part of the world. The possibilities really are endless.

What’s your chief enemy of creativity?

Time – either not enough of it or too much of it!

You couldn’t live without…

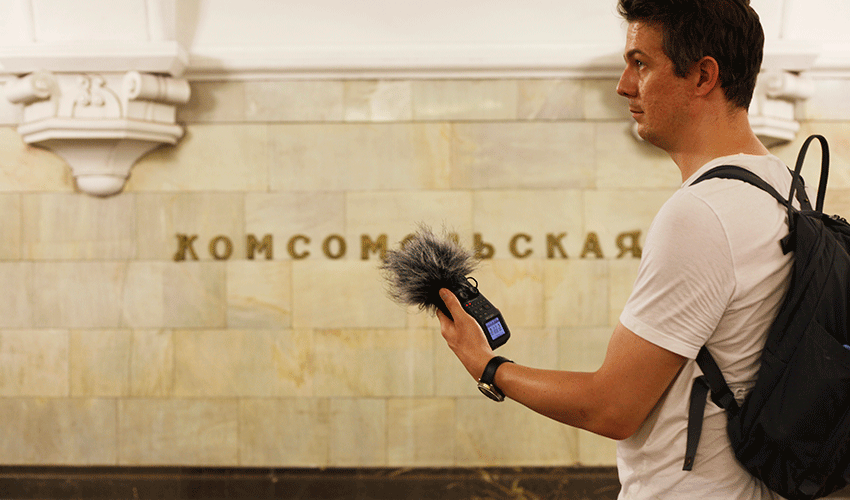

Well, I suppose that’s an easy one – my handheld recorder, which started off the Cities and Memory journey and without which the project wouldn’t exist. It’s my extra pair of ears with which to hear the world better.