Text by Ed Harrington

In their exhibition Moonquake, technological artist Dan Tapper and creative imaging specialist and archivist Laura Margaret Ramsey let people experience the moon’s seismic behaviour in an extraordinary way. The exhibition consisted of two chapters, Grounding and Moonquake. Using collected data of the moon’s seismic patterns and some imagined elements, they created an explorative space that observed our connection with the moon and the ethereal resonance of moonquakes, transporting visitors to the moon’s surface. Mapping historical data into sound, real-time visuals and sensory atmospheres, the events created a meditative and thought-provoking experience for visitors.

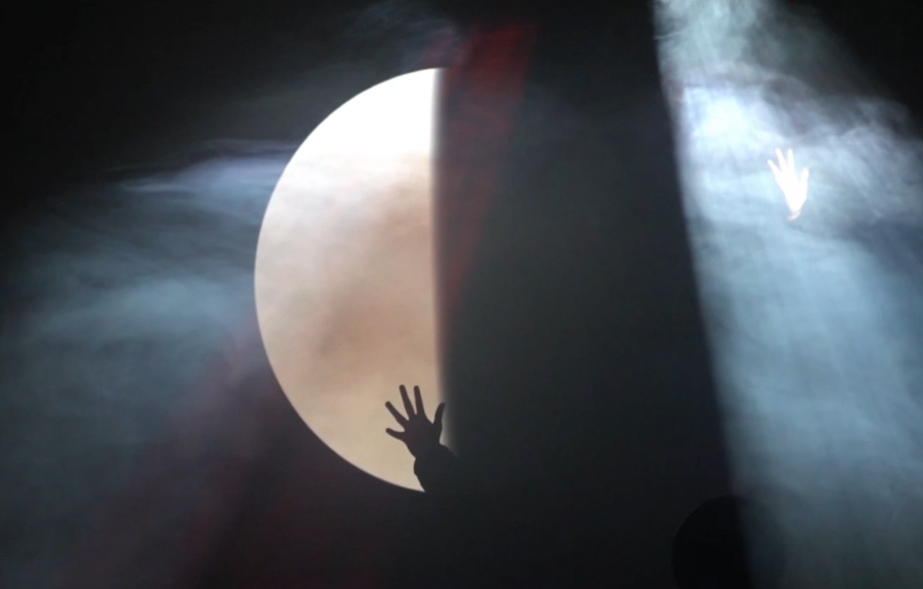

For the first installment, Grounding, they used projection mapping to show reanimations of the first images of the moon and enhanced the first seismic recordings of the moon by adding their own recorded sounds of ice and water to create an ambient, immersive atmosphere. The experience put people into the space of the very first astronauts who landed on the moon, like revisiting them through time in an abstract way.

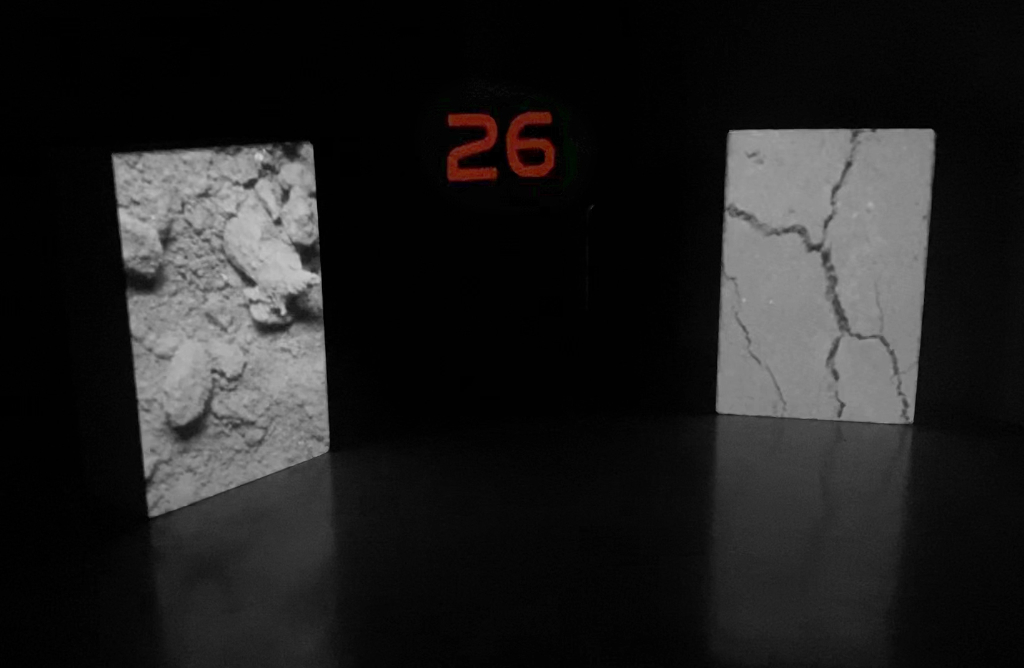

L. M. Ramsey explained how this came into development. I started working with archival data from the Apollo missions back in 2018. I was initially interested in the images taken on the lunar surface during the missions 11, 12, and 14 using what was called the Lunar Surface Close-up Camera (LSCC). This camera recorded two images simultaneously, allowing for the creation of a stereographic or 3D image of the surface material or what is known as lunar regolith. I was able to get high-resolution scans of the original negatives from the NASA archive to assemble animated GIFs to reanimate the 3D effect. Dan and I used projection mapping in the exhibition space for Chapter 1 to show these re-animations.

Dan Tapper spoke about the intention of Grounding and how they used sound and imagery to introduce people to the concept of seismic data and transport them to an historical place. In Grounding, we wanted to set up an environment that introduced visitors to the concept of moonquakes, the fact that the moon vibrates and that this data has been recorded and catalogued. We also introduced more terrestrial recordings of ice shifting and contracting which acted as a sonic analogy to contractions on the moon’s surface from heating and cooling. The installation acted as an entry point not only to the concept of seismic data recorded on the moon but also linking back to the first explorations of the lunar surface conducted by the Apollo 11 astronauts.

When talking about the outcome of the process, L.M. Ramsey expressed her satisfaction with how she and Dan worked together and how people reacted to the first instalment. Ultimately, we found a good balance with each other. After we decided on the sound we liked, it really just came down to the timing of everything—the visuals, the clock, etc. People who came really seemed to enjoy the space and stayed for several hours, sometimes talking and sometimes just watching this projected moon. I found it all to be very healing and romantic.

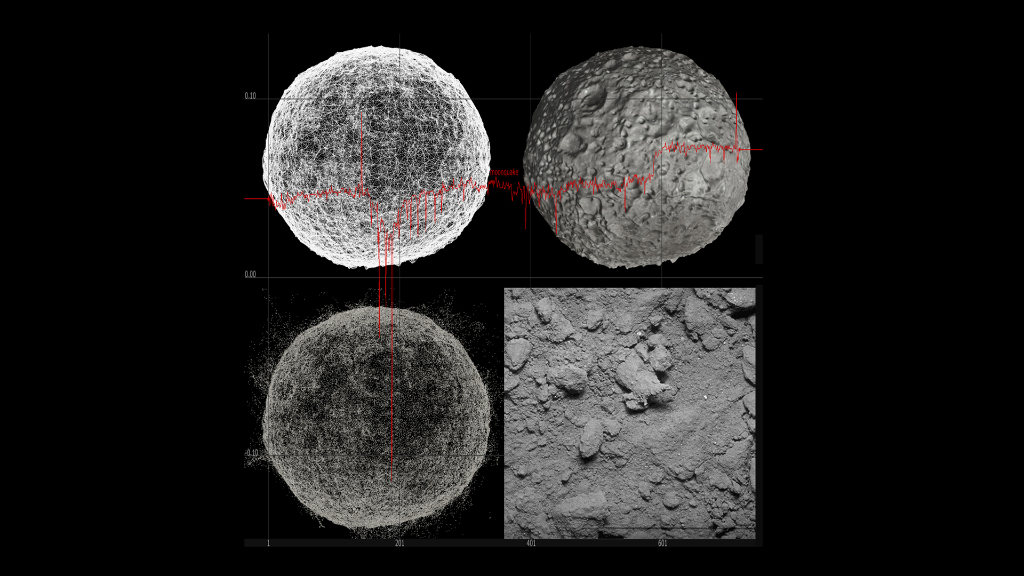

The second chapter, Moonquake, was much more interventional, letting people understand what a seismic moonquake might feel like. Using custom-built bass transducing seats, they orchestrated a space that fully enveloped visitors into the experience. The installation compressed the moon’s seismic activity of 1977 into an hour-long cycle, incorporating a veil of laser light that traced the data visually in real-time. Using a process known as data audification, L. M. Ramsey explained how they mapped the data, which had 273 directories, into vibrations.

We focussed on seismic data from the year 1977 which had 273 directories of data. We mapped this data to vibrations, looking at amplitude over time. I had some square plinths made for a previous exhibition, and we decided to reuse them as seats in the space. It was a fun day together, stripping wire and screwing the bass shakers to the bottom of each seat. Once we had everything working, we decided that it would be nice to have a visual ‘map’ of what you were feeling. Dan and I, in a very early conversation, had both agreed that we wanted to work with a laser, so we used this as an opportunity to do so.

The installation builds on cyclical themes, for instance, the placement of a circular moon at the centre of the space and a cone of light accompanied by recordings for the first installation. Showing this interplay between the first and the last seismic recordings of the moon created a clocklike sense of relevance between the ever-changing nature of the moon and its connection to the future. L. M. Ramsey further explained how moonquakes have an intrinsical, harmonious link with Earth. There is a deep moonquake every 27-28 days, which is the amount of time it takes for the moon to orbit the Earth. Just as the moon affects our tides, we, in turn, affect our moon a great deal. You see, no water or vegetation can absorb these internal vibrations. So when the moon quakes, it quakes on for hours like a bell in the dark sky.

Dan Tapper expressed that, whilst giving a perspective of the cyclical nature of a moonquake, these aspects of the installations also encapsulate the full nature of the moon and its geological traits. Quite early on in our collaboration, Laura and I identified shared interests in cycles of deep time. The moon is a very concrete link between our planet, its history in the solar system and to the wider vastness of space. Cycles of the moon define calendars and tides, but we don’t often consider the influence the Earth has on the moon beyond its being an orbital body. The cyclical nature of moonquakes is spotlighted in these installations, but I think there is also an element of voicing and meditating on the day-to-day geological activities in the moon that have been occurring for aeons and will go on occurring until the earth and moon are enveloped by the sun.

He also talked about their organic approach and how they wanted to create continual pieces that remained true to the data while giving people their own space to use their imaginations. Our trajectory of conceptualising the experience was fairly organic. It was structured around some core ideas while also allowing room for experimentation and play. We both wanted to create a series of works that remained true to the data while giving space for participants to be transported and engage with the moon through their own lens of experience. As a solo practitioner, it can be hard to make judgement calls around what is still authentic to the data versus too much creative licence. In our collaboration, there were moments when one or both of us would question a specific direction, and through deep dialogue, we were able to move both iterations of Moonquake into layered, distinct works that tangibly utilise different aspects of moon seismic data.

Moonquake manages to expand people’s understanding and perceptions of the moon and catalogue incredible information about the moon and its atmosphere, allowing us to be a part of it both physically and mentally. Dan Tapper expressed their eagerness to create more installations with more sensitive moonquake data and to engage with scientists in this area, hinting at another phase of work creating spaces that encourage and enable others to create projects around the subject.

In addition to further explorations around the moonquake, we also hope to realise a third more community-based chapter where we hold workshops, work with creators who want to develop their own data sonification and multichannel sound works, and build a network of folks exploring and creating with seismic data from the moon.