Text by Simona Serban

The China(TO)wn exhibition conveys the forgotten stories, willful omissions, and accumulation of silences that exist beyond Toronto’s official heritage definition of its Chinatown neighbourhoods. The project aims to put personal stories and individual memory in conversation with state-sanctioned narratives.

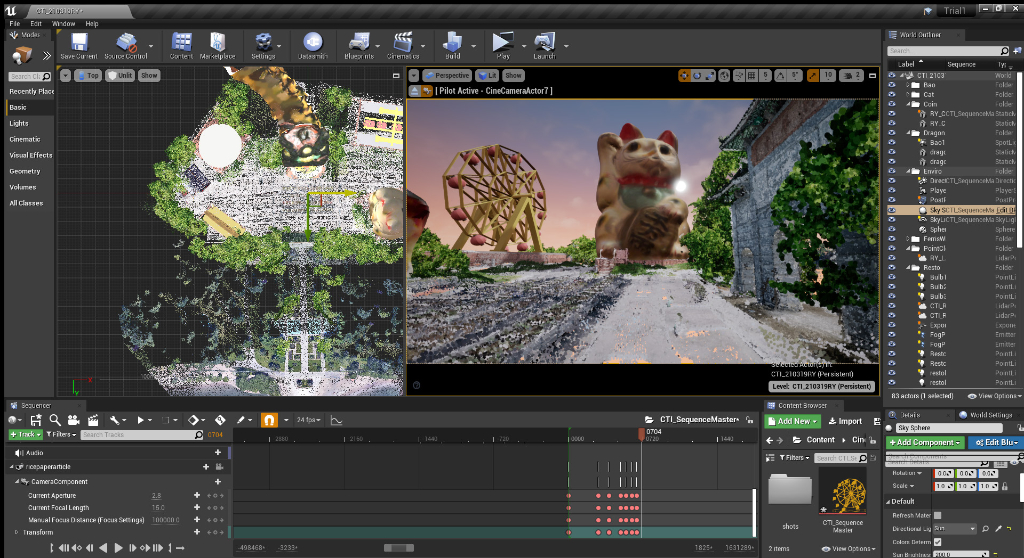

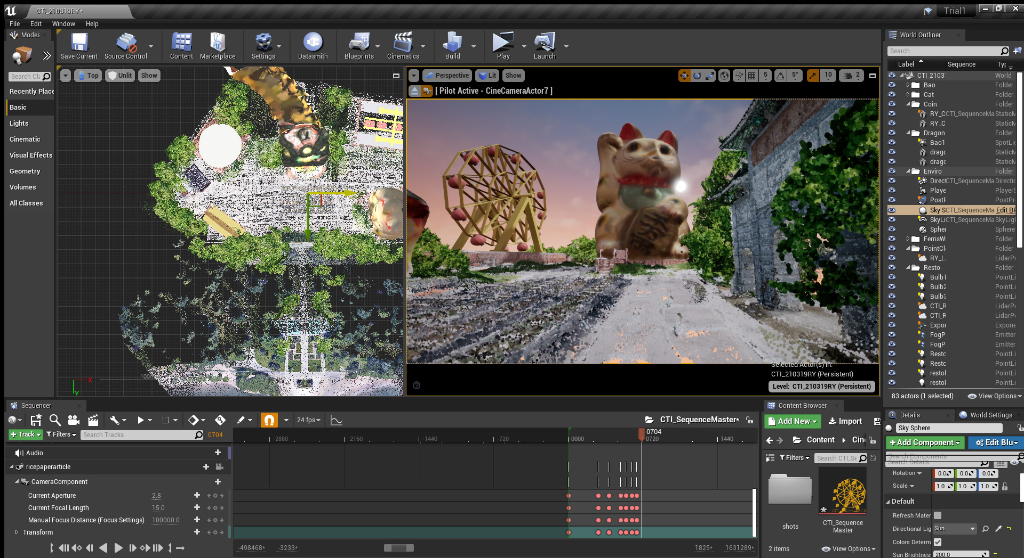

To convey all for the intricate aspects of what a Chinatown represents for the neighbourhoods and its people, to showcase the dynamic characteristics, architect and educator Linda Zhang mapped the buildings of Toronto Chinatowns with the use of 3D scanning technology alongside drones and in doing so, was able to bring to life and present to the visitors of the exhibition clear pictures of what, why and how Chinatowns are part of the neighbourhoods’ heritage.

Chinatowns all around the world can be described as a breath of fresh air for the local communities; Linda Zhang considers Chinatowns are born out of resistance; they radically resist fitting in, simply refusing to fit into what is considered national heritage, what is worth safeguarding by the City Council, or even the century-long attempts at implementing homogeneous urban planning ideals and city beautification projects.

Instead, Chinatown is a space that wants to expand the status quo. The richness and value of Chinatown are that it exceeds present-day definitions of city heritage or national belonging. And in doing so, Chinatown challenges us to think differently about the city and its constituents and make and hold space for more expansive communities.

Today we continue to see sentiments and desires to “clean up” (read: make it fit in) Chinatown with gentrification and beautification projects. And while the actors change, Chinatown remains a resistance. Resistance to a mainstream way of life within which it cannot neatly fit. And in that resistance, though always dynamic and constantly shifting, enough room is carved out simply for life to be lived. This is what Chinatown has always been and will always be. This is why Chinatown is essential and cannot merely be preserved as such but can be supported so that its spaces of resistance allow for life to be lived and lives to thrive.

When visiting the exhibition, the guests will get an amount of information on the history of Chinatowns, as Linda Zhang discovered alongside her student researchers that there is a sizable lack of documentation, architectural drawings and overall contextual insides about Chinatowns in Toronto.

Another insightful solution Linda Zhang and her team came up with was the ‘Build Your Own Chinatown board game’ that visitors will see during the exhibition visit, designed as a conversation starter, challenging the player to test their mindset toward the recalling and preserving spaces. The game gives specific instructions regarding the pieces that can come into play. The players must decide through the use of negotiations in Chinatown, as 99 game pieces represent individual Chinatown buildings, and just ten pieces are allowed to be placed on the game’s board.

The game, together with the exhibition, stands as a reminder that preserving cultures is an ongoing and persevering journey; it’s something that if we incorporate into our way of life, paying attention to the things that make us unique as well as to the elements that we appreciate in different cultures, we might get to see a colourful world and maybe discover new colours in the long run, instead of an indistinguishable picture. Showing support for different cultures has always been essential in understanding ourselves, the people and the world around us.

As Linda states, the China(TO)wn digital symposium explores alternative practices for future heritage buildings that centre the community and push back against state-sanctioned notions of heritage and even “capital H” history. Marginalised communities have not succeeded in showcasing their uniqueness per se. I would argue that if they did successfully showcase their “uniqueness”, this would be a success for the City and mainstream society who wants to consume their uniqueness and cast them as foreign and other, which would be a loss for the community.

Instead, the alternative practices we explored looked at forms of community control and mutual aid that work to the existing longstanding systemic issues, opportunities, and progress achieved through grassroots organising and community mobilisation. These alternative practices do not aim to overcome the current system (for we would then just be placing one system with another). Instead, they seek to find the cracks and seams within the system and use those as moments to hold space, expand, and create a clearing for community life to thrive.

Toronto’s China(TO)wns convey why we should care about the world around us, about heritage as a whole and why we should look towards preserving history, rather than hide it or cover it; it should be celebrated! As you will find out for yourself from Linda Zhang’s words, this exhibition is an important piece of both Toronto’s past and present. Consequently, it should be regarded with great importance when planning for the future of cultural centres and heritage alike.

People. Chinatown is dynamic. It is a resistance by the community for its people and for a community way of life to be allowed to occupy public space and be lived. Heritage tends to focus on things: buildings, street signs, furniture. And it also tends to focus on historical things: 30 years older and above. Chinatown is not those things. Chinatown is its people; its heritage is a community way of life—of resistance.

The exhibition conveys the history of Toronto’s Chinatowns with the help of documented untold individual and collective stories with the use of extensive research, artefacts, bookworks, board games, ephemera, photographs, sketches, paintings, videos, installations, sculptures, collaborative community projects, archival material and complex analysis bound together with innovative digital technologies to portray and uncover the whole picture following reality. Alongside the exhibition, different types of activities such as participatory storytelling events, a symposium and roundtable discussion will take place in the process of seeking further uncovered untold stories to continue their journey of building a collective, intersectional vision for the future heritage(s) of Toronto’s Chinatowns.

A thoughtful comment that Linda makes regarding the question of how we can use technology to shape the spaces, and our future and create empathy towards all the surrounding communities and how she believes we can structure memories, thus protecting the heritage around us, focuses on how visual representation as a communication tool:

Technologies are opening up all sorts of new kinds of access. Ten years ago, it would not have been possible to 3D scan Chinatown as I am doing now. Its advancements in technology, both hardware and software, have made leaps and bounds in increasing the affordability of these digital technologies to the public. Soon, 3D scanning will be available on every smartphone. Similarly, you don’t see many photos of Chinatown in city archives until after film photography became affordable to the general public.

Today, the images contained within archive holdings typically weren’t commissioned but donated from private collections later. But if it weren’t for the technology, it simply wouldn’t exist. The multi-year project mentioned above called “Spaces beyond Imagination” actually seeks to address ways in which technologies can be leveraged to structure both community memory and community future, envisioning in a way that can not only safeguard heritage but also give agency to the community as stewards of their neighbourhood. The Build Your Own Chinatown Game currently on exhibit explores this as well.

Regarding the experience and what it would reveal to its visitors – the realities and challenges experienced by Toronto’s existing Chinatowns, with harsh conditions in these communities – I asked Linda what inspired her to showcase these issues using digital practices. This question revealed that she took us to her childhood period and how Chinatown shaped her reality:

Chinatown has been an important site throughout my childhood. Growing up in a small town in Ontario, Canada, we couldn’t get Asian ingredients in my hometown. Driving 6-8 hours in one day to Toronto to get groceries was normal, and Chinatown is where we’d always go. After living abroad for ten years in the US and Germany, I moved back to Canada in 2018.

I moved to Toronto for the first time. It was then that this project began. My work has always addressed the built environment’s questions of memory, heritage and identity. It often examines sites of contestation, but coming back to this new home, Chinatown was a site that was impossible to ignore. Chinatown has and is changing rapidly.

The pressures from city planning policies to densify and gentrify are currently unprecedented for the neighbourhood. What happens over the next decade will have an enormous impact on the legacy of the community for future generations.

I wanted to work with emergent digital technologies as a way to bridge access from institutions to communities. I have the privilege of teaching at a University, which also means I have institutional access to funding and equipment like drones for 3D scanning, training to become a licensed advanced drone pilot, access to photogrammetry (3D reconstruction) software, as well as access to powerful computers to process 3D scans at a neighbourhood scale.

These tools are commonly used in heritage preservation practices but are not (yet) available to community members. For example, Chinatown has not been well documented, and much of this is because it hasn’t been deemed worthy of the expensive cost of 3D scanning it. So the project began with a desire to document Chinatown as it was rapidly changing merely. We have been 3D scanning Toronto’s Chinatown East and West every year since I moved here.

The next question then began, how do we get these scans into the hands of the community? This is explored across all of the projects featured in the bilingual virtual reality (VR) exhibit, ChinaTOwn: Future Heritage(s) of Toronto’s Chinatowns, as part of the Museum of Toronto’s Intersections Festival. In one project, we place them in the hands of people as 3D-printed building game pieces in a build-your-own Chinatown board game.

In Memory, In Suspension, present-day 3D scans are used to reconstruct Toronto’s first Chinese-owned business, for which we have no architectural records. Finally, in Chinatown 2050, the 3D scans create immersive VR worlds to accompany speculative fiction stories written by community authors about what Chinatown might be like in 2050.

On the topic of why she chose to involve her design student researchers in the process of planning and creating thought-provoking installations for the ChinaTOwn project and what attracted her to this style of teaching, she highlighted her vision of that an architect and designer experience to become a better creative;

We rarely ever design for ourselves or in our community. As interior designers and architects, we are often hired by a client (or working for a firm) to work on a site we have often never been to before. So I think it is incredibly important for these young designers to learn how to engage with a site and community. They are outsiders meaningfully. Of course, some of the students were already part of the community, and some even grew up in the heart of Toronto’s Chinatown—which can sometimes make designing all the more tricky.

However, these students are our next generation of designers and will be our future. And so, I thought having these conversations in the classroom and through hands-on learning was critical. I was recently awarded the Provost’s Award of Excellence in Teaching (Innovation) for the course and innovative teaching pedagogy. And will continue this kind of teaching next year as a part of a multi-year Canadian Government-funded project that will create a VR platform that will allow communities to visualise and virtually shape their neighbourhoods collaboratively.

Through an interdisciplinary process, the project will identify the impacts of COVID-19 on marginalised people and the exclusion and displacement of racialised communities from the public space. Using VR and 3D building scans, the researchers will use an architecture-driven envisioning process to transform how communities and identities are built and mobilised and strengthen resilience to promote social justice and equity.’

I asked her if she had to put in a paragraph what would need to happen for individuals and communities to realise the true meaning and importance of having such culture-rich spaces around their neighbourhoods; she had this to say: ‘I believe that individuals and communities already realise the meaning and importance of culturally specific and rich spaces such as Chinatown.

This is why these communities have a century-and-a-half legacy of mutual aid and organising. This is also why there was a huge Save Chinatown campaign in Toronto when the city decided to expropriate and bulldoze old Chinatown to make way for New City Hall. Chinatown began out of the desire for such a space, to make such a space, to hold such a space. Yet, it continues to fight and resist to persist.’

In Linda Zhang’s words, ‘Toronto’s Chinatowns are here to stay!’