Text by CLOT Magazine

Omica is the result of a sound conversation between two participants with the necessity to capture a future energy that goes beyond the present. A journey full of changes that oscillate between the revolutions of biomechanical machines and a constant light that bends time, as well as a fluid that pumps through cables, creating structures and rhythms within a fickle space. Olor Acre explained their new release, Omica (Hedonic Reversal, 2023).

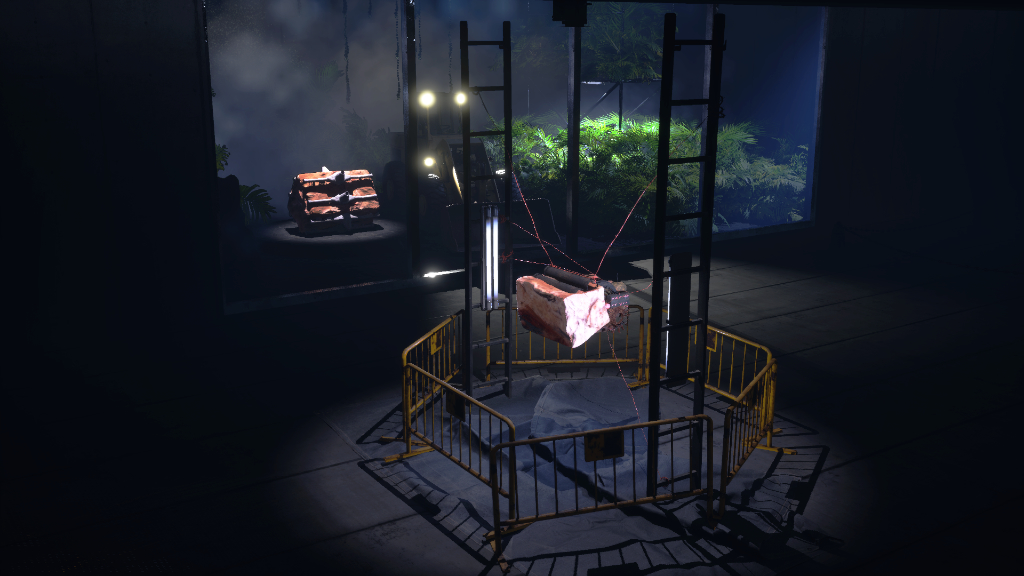

For Omica, Olor Acre (Erik Paterna aka Stmkh and Xavier Longàs aka Refectori) has created a 3D environment resembling a first-person video game to experience the music in a virtual immersive world, expanding the expression of music and creating a much more significant impact on the receptor. With a close friendship and shared experiences, since they were teenagers, their artistic interests have always been related to visual and sound design. Hence, they felt they had to show the project in a place that could be sheltered and potentiated. It was clear to us that our creation was through virtual reality, a lobby gathering the album’s essence. Stmkh and Refectori explained.

While creating the album, they also worked on a video game that helped them take that step into VR to add to the project produced with the graphic motor Unreal Engine. Gaming and expanded realities are pushing narrative and storytelling into new territories, and virtual reality for artistic purposes has to be seen as a new language and way of expression. The way in which it is used and its intended purpose has a very broad threshold, like AI. We believe they are compelling tools, and they still have to settle. They said.

Olor Acre expanded this idea: At the moment, of all the VR projects we have tried, this technology in horror video games has surprised us perfectly. It’s something that will end up being much more significant in the near future. VR could be a new form of art that does not have to be accompanied by other forms of expression.

When we asked about the challenges, they clarified that the most complicated bit of the process has been the environment in VR, as the assignment of controls and the full export to run the archive. They believe total immersion in these spaces is the most challenging thing yet to be achieved in many VR projects. Like all art preceded and defined by emotions, VR has the same way of being read through feelings that may or may not attract and convince the user. The use of detail in certain aspects, such as sound, enhances this technology. It is undoubtedly a way to grapple the user.

Their long interest in biomechanics in their visuals (like the heart suspended in wires) and sound aesthetics comes from their mutual taste for apocalyptic images. The contrast of life and death has always been an idea they wanted to work on artistically.

They tried to portray this idea through machinery sound that goes together with an alive surface, like a light that defines a path. For us, this idea translated to a sound process; it’s described with solid percussion that oscillates the beats, creating constant acceleration and changes of rhythm, while there’s space for melodies to represent the most organic and alive part of the result. Our automatism comes from assigning levels of chance that end up with aleatority chosen by the software. This leaves us space to add on a melody created by a human process. We translate the idea about biomechanics to sound this way. It’s about the contrast between the light that defines the emotion and death translated to mechanics.

This interest in biomechanics can be seen in the album cover: a heart made out of flesh and mechanical elements; this was the main idea to execute the sound. Then, in virtual reality, they decided to show the organ in a digital lobby, an exhibition room, to be able to contemplate it. There’s a cut of a song from the album inside that room in surround format, which helped and convinced us to encompass the space with the album’s tone. Depending on the point where the viewer is, the depth of the sound changes.