Text by Lyndsey Walsh

Capturing the echoes and reverberations of human disturbances in the environmental cycles spiralling us into our current global climate crisis, Vicious Cycle at Art Laboratory Berlin reflects and probes into the push and pull dynamics of anthropogenic and environmental bodies.

The exhibition, curated by Tuçe Erel, Regine Rapp, and Christian de Lutz, features artworks from artists Cammack Lindsey, Gülşah Mursaloğlu, and Sybille Neumeyer and runs alongside a series of programmed artist-led events.

The exhibition’s curatorial concept emerges from a paper published in March of 2022 in the journal Environmental International entitled Discovery and quantification of plastic particle pollution in human blood. In the article, researchers found that microplastics were present in the blood samples of about 77% of their study group [1]. This finding has led to the breakthrough realisation that microplastics are not only polluting our oceans, soil, and food, but they are also now polluting our bodies.

The long-term implications of microplastics in our blood are currently unknown, but the researchers of the study are highly concerned with the potential hazards posed by them. It is suspected that these microplastics can accumulate in the body, potentially cross the blood-brain barrier, and secrete toxins over time [2].

This turn of events marks the truly “vicious” cycle that the impact of human-led pollutants and industrial influences has had on both environment and the rest of humanity. In the face of the global climate crisis, these cycles are even more apparent and alarming.

Embodying the inspiration for the exhibition, Gülşah Mursaloğlu’s work Devouring the Earth, in Perishable Quantities materially, sonically, and visually draws us into the problems concerning the presence of microplastics. The installation features a set of washing machine filters cycling different microplastics in a liquid medium, thereby examining and manifesting processes of leakage, amalgamation, and digestion. In referencing practices of geophagia, or eating dirt, artist Mursaloğlu excavates the long history of human and non-human connotations of these practices while probing into the contemporary context of our current reality, where foreign substances and matter are finding their way into human and non-human bodies through the continued consumption and proliferation of industrialised material goods.

While human practices of eating dirt can border taboo, as it is of the psychiatric view that the act is a form of a compulsive eating disorder called pica, geophagia is also considered to be an act of consuming important minerals outside of a western lens and a medical indicator about the state of health of an individual [3]. The act of eating earth also is pervasive in cultural contexts. In Dolores Reyes’ novel Eartheater, book reviewer Noah Berlatsky described the act being attached to a two-sided metaphor of connecting to the earth and those who have been lost to it, while it is also associated with being mentally ill and suffering from PTSD [4].

Outside of the human perspective, non-human entities that eat dirt are greatly impacted by the spread of microplastics in soil, as microplastics can accumulate in their bodies and break down in their digestive systems to form secondary microplastics [5]. Mursaloğlu’s work asks us to question the nature of eating, consuming, and devouring and the continuities of these rapidly spreading and pervasive substances that we are polluting the earth with, such as microplastics. In turn, Mursaloğlu brings to light the other agencies present in these cyclical dynamics.

Continuing Vicious Cycle’s examination of pollution, artist and performer Cammack Lindsey’s sound and site-specific installation Wem gehört die Welt? (which translates to “Who owns the world?” in English) materialises from Lindsey’s ongoing research examining cyanobacteria blooms and Berlin’s local lake Müggelsee.

The artwork’s name comes from the 1932 film written by Bertolt Brecht and directed by Slatan Dudow entitled Kuhle Wampe oder Wem gehört die Welt? The film is set in the early 1930s and follows a Berlin family as they lose their housing and relocate to Kuhle Wampe. Kuhle Wampe itself is an actual place near Müggelsee where historically, many unemployed and unhoused individuals lived during the late 1920s and early 1930s [6]. The film is characterised by its notable perspective on the social issues emerging from the end of the Weimar Republic and its initiative to capture working-class issues from a proletarian lens. German Studies Professor Marc Silberman’s critical analysis of the film asserts that the film works not to necessarily clarify the causes related to issues of class that resulted in the rise Nazism and the National Socialists during this time, but it provides a narrative about the powerlessness and consequences of apolitical behaviour [7].

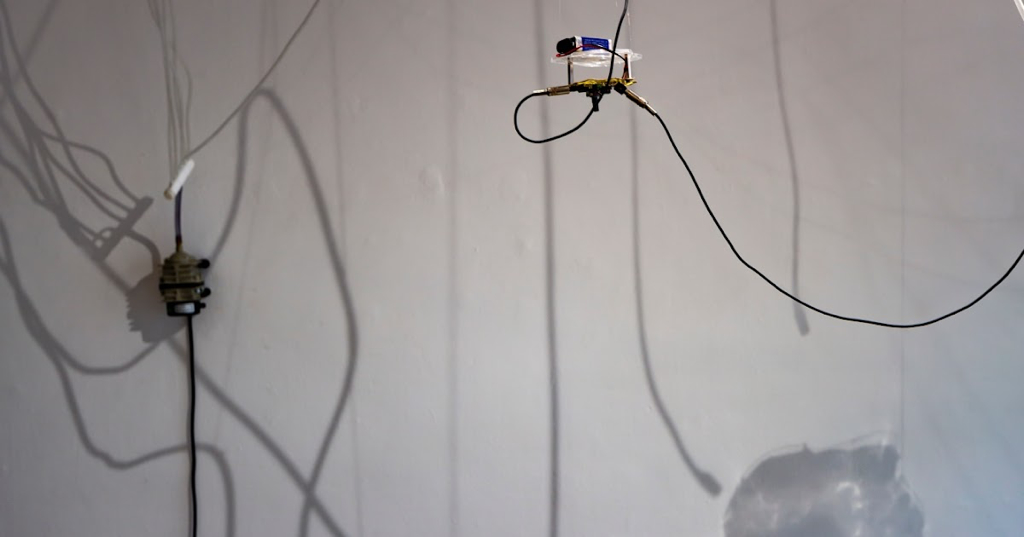

Sharing in name and location of interest, Lindsey’s work follows suit with the film to piece together stories emerging from the Müggelsee area of Berlin from a proletarian lens while also considering the present, but often neglected or ignored multispecies entanglements. The artwork features sound recordings taken from Müggelsee and generated sounds from living Microcystis aeruginosa from Müggelsee water samples. These samples are housed in a hanging pooling network system, which takes its shape from colony formations of this cyanobacteria species.

The work hangs above an illustrative map of the Müggelsee landscape, giving audiences a chance to inspect the growth of these organisms while anchoring them to the location where they were sourced. Wem gehört die Welt? examines the human and nonhuman tensions surrounding water quality to investigate how cyanobacteria blooms at Müggelsee relate to the economics of water, addressing its price, its consumption, and water treatment strategies. It also brings attention to the inherent and historical political connections of Müggelsee’s environment and the resulting tensions between human and non-human agencies.

Aligned with this thread of artistic analysis concerning the entanglements between human and non-human agents, artist and researcher Sybille Neumeyer’s installation and speculative video essay souvenirs entomologiques #1: odonata/ weathering data explores the interactions between weather, human, and insects that are embedded in a data-driven world and embroiled in the catastrophes of the climate crisis. Neumeyer’s work focuses its examination on dragonflies, looking at their presence and digital extensions on multiple scales, including both space and time.

Neumeyer sets out to examine how technology, through data-driven ontologies, changes how we view and engage with a species and its future. Her questions emerge from her stay as a guest researcher at the Natural History Museum of Berlin in 2019/20, and the project was developed in 2020 in collaboration with The State Museum of Natural History, Karlsruhe. In reflecting upon the process of the museums digitising their collections, as well the role of the digital in scientists’ research and fieldwork, Neumeyer’s resulting work ponders on these tensions between nature and technology.

In light of the climate crisis, souvenirs entomologiques #1: odonata/ weathering data asks how a species can “weather” these ongoing struggles. The idea of digital representations of species is becoming increasingly popular in contemporary environmental and conservation discourse.

For example, Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg’s The Substitute explores these issues through a design project aimed at resurrecting the Northern white rhino in avatar form. Comparatively, Jonathan Ledgard’s concept of “Interspecies money” applies digital avatars that are given a sense of power through spending agency facilitated by the use of their own digital wallet [8]—a concept bleeds over into sci-fi imaginaries in Ned Beauman’s horrifying dystopic vision in his 2022 novel Venomous Lumpsucker, which envisions a future of companies buying and selling species’ assigned extinction credits for the rights to wipe a species’ existence out from the planet. These projects feed a burgeoning desire to find ways to digitally preserve and embed conservation strategies into data-driven technological applications when a species is under threat or facing impending extinction.

However, Neumeyer’s work focuses on the context of these digital extensions and the stories that data can tell us about dragonflies, their environment, and their relationships while also looking at the specific context of their use in museums. The framing of the word “souvenirs” in the project’s scope critically reflects on what it is humanity is gaining from our current and emerging practices in Entomology, or the study of insects. Entomologists are known for their vast collections of preserved specimens, which usually end up in the hands of museums or other types of institutional archives. Neumeyer’s installation and video essay question how these data-based ontologies enact practices of care for a species that can live beyond their usefulness as data.

The Vicious Cycle presented in each of the artist’s works spark meaningful insight into the complex issues the world and humanity are facing. With each work serving as its own carefully crafted investigation, we, as the audience, can dig deeper, reflecting on both our past and present, as we try to collectively move forward and find a way to escape the hold these cycles have on us.