Interview by Giulia Ottavia Frattini

The present is as much an abstract construct that seeks to impart order or grasp the impermanence of temporality as it is an experiential state we shape and that relentlessly spans us. The present is also said to be elusive, yet its intrinsic ephemerality remains a constant that unwinds into infinity.

The artistic expression may not escape from infiltrating or being penetrated by time, which is arguably the primal entity or notion delineating its inclinations and urges through the epochs. Following this thread, technologies are tenants of the progression of time as they respond to the needs that arise either by pandering to them or questioning their stances. Technology itself is defined by its permanent state of liminality suspended between innovation and obsolescence. It inherently entails the combined application of multiple disciplines and is driven by procedures rather than products.

Time-based artworks have duration as a dimension and unfold their language by exposing it to the viewer over time. The media that are encompassed by this production and expressive orientation include video, film, single- and multi-channel installations, multimedia environments, performance, sound, and virtual reality.

These constitute the core and the nature of the JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION, which for fifteen years now aims to shed light on time-based art practices through focused research and emphasis on the cited positions and technologies. With a keen interest that stems from the experimentations with the moving image dating back to the 60s and 70s, the collection is representative of the unfolding of contemporary and progressive artistic discourses.

Heterogeneous intuitions and domains’ cross-pollination compose a collectivistic corpus that embraces over 870 artworks by 290 artists from around the world. The creative perspectives comprising and informing the two strands of the collection, the foundational in Düsseldorf and the most recent in Berlin, aspire to portray to the audience a selection of the crucial voices belonging to a “now” that is perpetually in transition.

By capturing the current times and presenting the past decades through sharp sensitivity and technical excellence, specifically in terms of conservation strategies, the JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION represents a leading contribution to international artistic dissemination.

In conversation with Robert Schulte, Head of JSC Berlin, a comprehensive approach that aims to be both repository and catalyst of artistic languages significantly constellating the global creative scenario is disclosed.

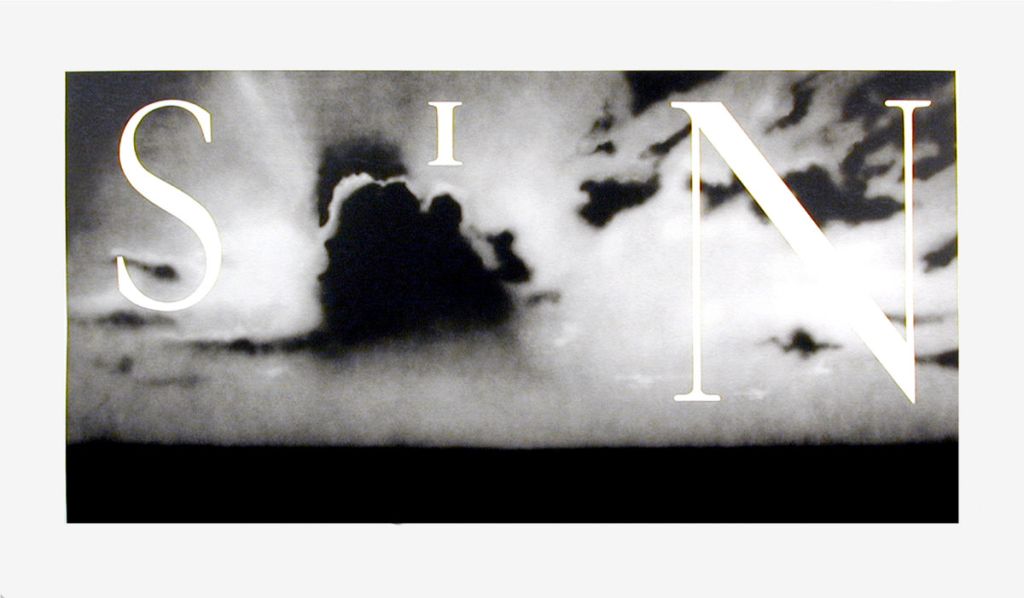

Right: Sin-Without, Ed Ruscha (2002). Courtesy of the artist and Brooke Alexander, Inc., New York

The JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION is one of the most miscellaneous and cutting-edge private collections in the current scenery. Would you like to provide an overview by referring to the driving principles behind the pieces included, the positions represented and the past and forthcoming acquisitions?

First, the Julia Stoschek Collection aims to create an overview of time-based media art – from the beginning in the early 1960s to today, focusing on film and video but also spanning VR, audio and computer-based works, performance, and photography. Second, critically reflecting that overview means representation; the collection tries to reflect a variety of voices, artists, subjects, and styles. Around 40% of the artists in the collection are, for example, female or non-binary.

We are still at a point in time where this is an exceptionally good ratio for an art collection with many works from the 20th century. We think about what kind of history we would like to write, strive to be as comprehensive as possible and still have a ways to go. Thirdly, a private collection also reflects the collector and the team. This is what artist Ed Atkins has identified as a “thrilling whim”.

Some decisions are made following an impulse, guided by intuition, both corresponding with artistic inventiveness and young artistic practices. Numerous times, JSC has taken on artists before they appeared in the centre of the market attention; you can take Ed Atkins as one good example.

How is the dual exhibition lineage structured in the two locations of the collection? Is there a peculiar divergence with regard to the shows held in the cities of Düsseldorf and Berlin? And are any differences discernible at an audience scale?

The audience is different. Düsseldorf is known for its avant-garde in the 1960s and 70s, which still is very present in the city today. The same can be said about the nearby Cologne and the 1980s and early 90s. The audience in Düsseldorf, to a large degree, comes from the region and brings a certain shared background with them, a very knowledgeable perspective on contemporary art history. In Berlin, the audience is larger, younger, and international. More experimental programming stands an easier ground. With this difference in mind, we work against pleasing our audiences wherever we can.

The infrastructure is different as well. This is reflected when making exhibitions: the historical industrial building that houses JSC Düsseldorf is owned by Julia Stoschek, has a higher technical standard, and the exhibition spaces are separated mainly through the sound-absorbing glass on two floors, which creates a situation where you oversee an entire floor. JSC Berlin is located in a 1968-built representative GDR building with cracked marble tiles, in which exhibitions need to embrace the rough conditions at hand, adapting to many different-sized, stripped-down rooms, a wood-panelled cinema and a barren basement.

This year marks the 15th anniversary of the collection. Which exhibitions have you recognised as the most seminal, prominent or controversial since the establishment of the collection? Is it possible to identify some turning points in both the artistic and curatorial choices?

NUMBER ONE, the first show in 2007, was in some way decisive for the reception of the collection. Until this point, no one knew what to expect. With the opening of the premises and that exhibition, Julia Stoschek entered the stage as a collector with a public institution. The presentation was perfectly clear about the seriousness of the entire undertaking, and from that very first appearance until today, we are happy to hear that the public in general and the art world associate JSC with high-quality output.

There were a lot of well-executed collection exhibitions in Düsseldorf and Berlin as well as internationally. There were historical solo shows like Derek Jarman’s Super-8-exhibition (2010) and STURTEVANT (2014). There was a one-year-performance-program called HERE AND NOW 2009 with Joan Jonas, Tino Sehgal, Allora & Calzadilla and more, or MISSED CONNECTIONS, which presented artists like Sondra Perry and Sandra Mujinga in Germany as early as 2016 that were ahead of their time. To name two special moments: Ed Atkins’ 10th-anniversary show GENERATION LOSS (2017) extended the realm of video art exhibitions. Arthur Jafa’s A SERIES OF UTTERLY IMPROBABLE, YET EXTRAORDINARY RENDITIONS in 2018 was a special exhibition in terms of timing and reception.

An obvious turning point was in 2018 when for the first time, a visible curator joined the Foundation, Lisa Long. Her initial exhibition program, HORIZONTAL VERTIGO, included solo presentations by Meriem Bennani, A.K. Burns, Sophia Al-Maria, WangShui, Rindon Johnson and more in 2019-2020.

What are the challenges and stimuli in collecting time-based art? How would you define the relationship between art and ephemerality? And how does one become a catalyst of significance for the other?

Technology is a big challenge, both in terms of conservation and exhibition-making.

To meet the different requirements for conserving the collection’s media-based art, a multistage strategy for long-term archiving was developed based on the “three-pillar approach.” The goal is to consolidate the heterogeneous collection on a digital level in just a few established and homogeneous target formats. This noticeably reduces the conservation effort since only a manageable number of formats need to be regularly checked and monitored to safeguard against formats that are becoming obsolete. This is flanked by individual solutions for artworks that do not support a standardized procedure.

In terms of presentation, the technological requirements for the presentation of even more works have become noticeably more complex over the last ten to fifteen years. For the audience, this means nuanced sensual experiences; for the institutions, it means a professionalization towards high-end. Not all can keep up with that. Speaking for the German institutional infrastructure, some publicly funded houses don’t have the possibilities. This development changes the parameters for the calculation of a possible acquisition: in the past, you would only consider a work’s sales price, as installation costs didn’t diverge too much for certain kinds of works (one-channel, two-channel), which were not obviously extremely installative. Today you need to take into account the artist-intended technological requirements of each work individually and see how often you will actually be able to afford an installation after the work is acquired.

Concerning the conservation of artworks of a digital and video nature, are updates as impending and urgent as the speed of technological advancement? Is there a nexus between the concepts of obsolescence and aura?

Conservation can be tricky when artworks depend on cutting or bleeding edge technology as specific expert knowledge needs to be obtained. Often it’s the artists themselves we can ask: Ian Cheng’s software for BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018-19) is a black box for us. There is no way of reaching into it from our side.

For obsolete technology, the works’ content is conserved through transfer onto safe formats. The older the media get, the more vulnerable the original way of presenting it becomes, which is what we aim to do if possible. Therefore, we are always looking out for specific second-hand tech like old televisions, which we need for some of the works in the collection, as a whole or for spare parts. For some of the old media, we need to consult specialists, but our conservator has a great network of experts in a variety of fields.

Obsolete technology starts to radiate aura, is my perception. Paul Pfeiffer’s Empire (2004) runs on a rack of hard disks connected to a computer from about the time the work was made. Today, the materiality of this setup feels more present within the installation than I suppose it was in the mid-2000s when people had similar objects at home.

Temporality seems to become a progressively fluid state of perception and condition, with an almost fractal rather than a linear course. Artistic research appears to be shifting and drifting towards interdisciplinary approaches by infiltrating multiple domains, bridging divergent knowledge and bringing them into dialogue or confrontation. The media can be conceived as the heralds of the epochs in which they are employed. How would you depict the “now”?

As an infinitely complex chaosmos, whose image will never be fully adequate. Transcending disciplines seems to be a vital way to deal with this condition.

What does the JULIA STOSCHEK COLLECTION aspire to convey to the future, and what are the most compelling speculations animating the current creative landscape and impacting the collection’s identity?

We hope that JSC will be the collection you look at for an overview of the greatest time-based artworks of their respective periods. At the moment, we are on the brink of technological developments that will enhance the way you experience time-based media art, and it would impact the collection’s identity if we did not support them.