Text by Juliette Wallace

Remaining true to her 1% disorder practice, the seminal 20th-century computer artist Vera Molnar died just one month before her 100th birthday. Before her passing, she and two curators – the established multi-media producer and curator Richard Castelli and Budapest’s current Ludwig Museum on-sight curator, Zsofia Máté – had begun what was to be a celebration of Molnar’s extensive career.

It was also to be an opportunity for the artist to meet fifteen of her proteges from the contemporary generative/computer art scene. The eventualities that took place at the end of 2023 meant that Molnar would no longer be able to participate in person. This changed everything for the curators.

What was at first envisioned as a coming together around Molnar in her hometown of Budapest became a joining up of creatives to honour the great artist’s memory. An homage, as Vera herself was known for, in the absence of the artist. The resulting travelling exhibition, beginning at the Ludwig Museum, is beautiful and simple and does justice to Molnar’s legacy and character.

Perched on the Danube River, the Ludwig Museum is a modern temple of art. In keeping with the lofty museums of the turn of the century that presented the viewing of art as a spiritual experience, the Ludwig’s slick, dominating yet peaceful presence makes one aware that they are entering a space divided from the everyday, where big exhibitions by big artists take place.

Founded as a museum proper in 1991, the Ludwig Museum’s remit is works of the mid to late 20th-century and contemporary 21st-century artists. Being one of the city’s primary art spaces it is a fitting place for a homegrown Budapest artist (spanning across both centuries) of such calibre as Vera Molnar. It was important for us to show Hungarians themselves Vera’s work. Compared to the rest of the Western world, the Hungarian population is not so familiar with her art, Zsofia Máté explains.

Although Vera Molnar was born in Budapest, she left her hometown early on, at the age of 23. She and her husband/artistic collaborator, François Molnar, went on to spend the majority of their lives in Paris, where they actively partook in the academic, progressive art scene. There they founded GRAV (Group de Recherche d’Art Visuel) amongst other inquisitive and research/practice groups and were productive in their own art practice. The works they made and the bold modes of thought that they employed would go on to permeate not only the Parisienne but the global art scene.

Curator Zsofia Máté told the author that she saw this opportunity to begin the journey of a travelling Vera Molnar exhibition in Budapest as a way to give the artist’s own people the chance to not only see her work but grasp its influence on the art world at large: even if the space is limited, the exhibition shows the full cycle and influence of Vera’s career, pre- and post-computer, from the late ‘50s to 2023.

In the same way that Budapest is a city divided and yet connected, the temporal element of À La Recherche de Vera Molnar employs the same dichotomy. Like the many bridges that join the two sides of Hungary’s capital, this exhibition creates temporal bridges in the form of homage where the past, present and future are all interwoven in a tip of the hat from one artist to another, with Molnar at the centre. A generational Mexican wave, if you will.

As such, the curators’ decision to create a homage exhibition was rooted deeply in the title artist’s practice. This can be seen in the very name of the show, which quotes Vera’s homage series À La Recherche de Paul Klee, simultaneously honouring the Swiss/German expressionist artist Paul Klee and Marcel Proust’s seminal work À La Recherche du Temps Perdu.

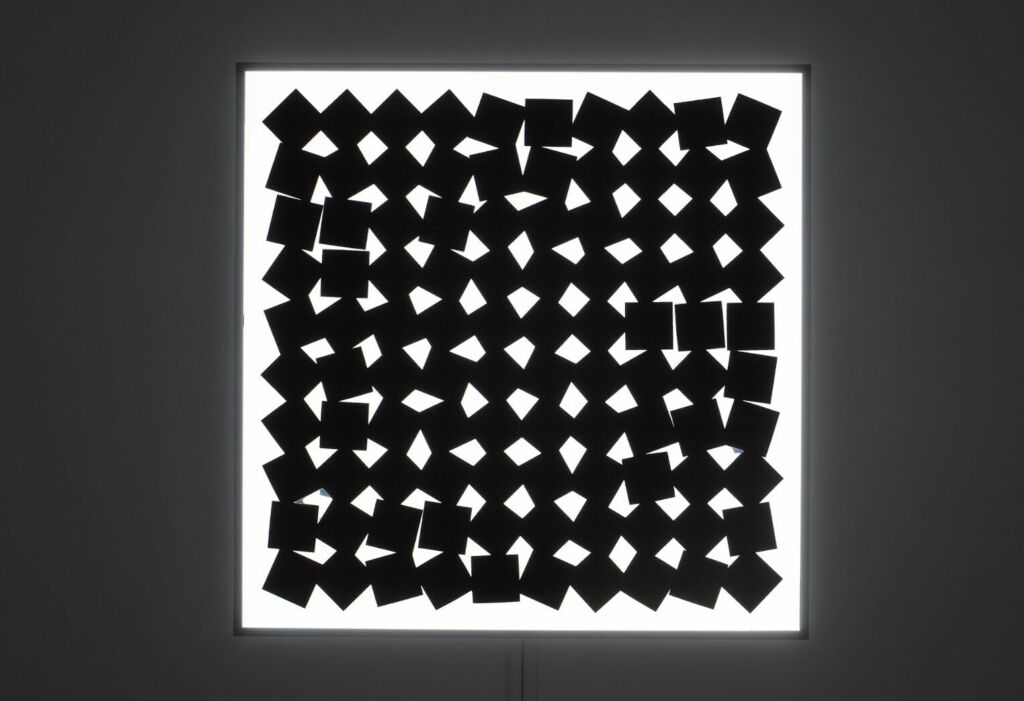

Going as far back as the 15th century’s Albrecht Dürer and his “invisible square”, which features not only in Molnar’s works but also in contemporary pieces, including the sculptural homage Asking a Shadow to Dance (2004) made for Vera by the French art collective U2P050, the exhibition does what few tech shows can: it seamlessly blends previous generations’ progress with contemporary developments without being didactic.

The exhibition is able to comfortably span centuries whilst never losing the fundamental thread of the aesthetics of generative and computer art. How? Through Vera Molnar’s unquenchable curiosity together with her unique interest in combining the new with the old, technology with history, the “then” with the “what now?”.

The most recent of Molnar’s pieces in the show – a series of NFT (Non-Fungible Token) works made in collaboration with Martin Grasser in 2023 – exemplifies this philosophy. Vera’s use of NFTs not only makes her more accessible to a contemporary audience, but it also demonstrates her character. At 99 years old, Vera was still experimenting and exploring the technological landscape, states Máté. It is true that the NFT work is functional in converting a previous generation’s tech language into today’s.

Whilst in her lifetime Vera saw computers as a tool, there is no doubt that technology is becoming more autonomous, where artists and others can end up submitting to rather than making use of it. When asked directly by the author what role the computer and new tech play in the exhibition – tool, muse, hero, or villain – Máté ponders a while and then replies it’s an overachieving tool.

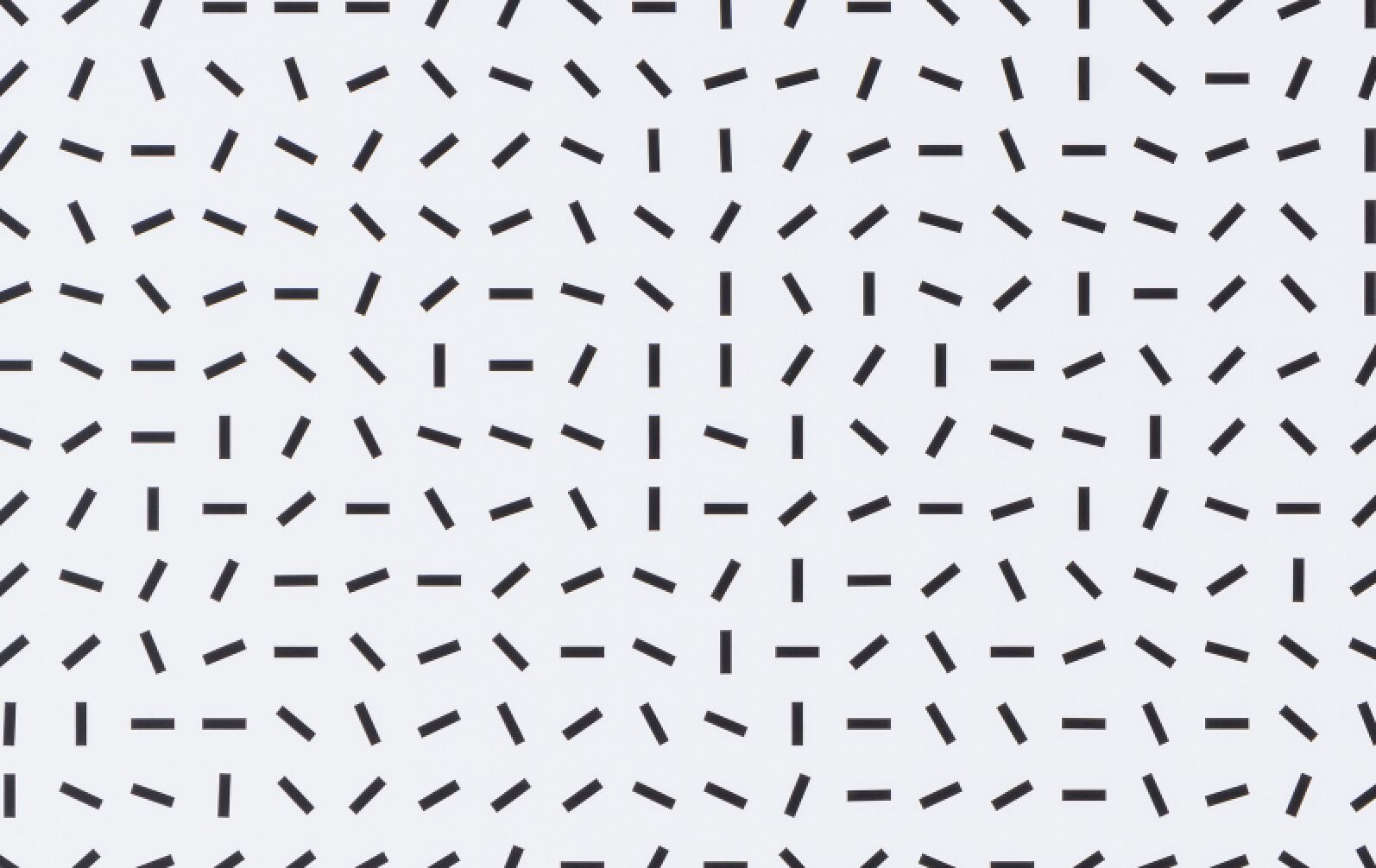

Vera Molnar was always fascinated by computers and considered them an exciting means to an artistic end. In her mind, the computer gave new language to self-expression: It makes desires and manias more accessible, and what is more human than that? Although at a glance, Molnar’s works seem structured and coldly systematic, the experience of actually being in the room with them at the Ludwig makes clear that there’s much more to each piece than an algorithm. Every work has its own particular vibe and human – specifically Vera – element. This is down to the artist’s nature but also to her employment of the 1% disorder rule, where each system was disrupted by 1%, causing what could be defined as “character”.

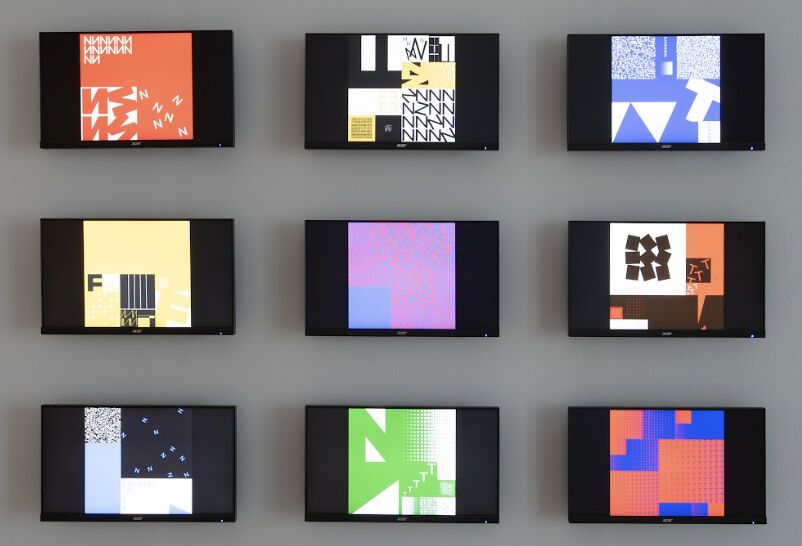

Of the fifteen contemporary artists who were selected to exhibit alongside Vera, each responded to the artist’s 1% rule in their own way. One of the more successful works that made use of this was Trame Temporelle by German artist Mario Klingemann. Made up of a grid of screens displaying live footage of the viewer shot by security cameras, Klingemann uses fractional disruption in the context of time, interrupting each screen’s footage with an exponential fragment of delay. This creates a ghostly likeness at transitional stages of the viewer’s movements.

This work has a distinct eeriness that only makes it more attractive to a curious gallery-goer. Another contemporary work, Homage á Molnar, by the established British digital artist Casey Reas, deals with this 1% by carrying it to its conclusion. By animating the varying angles of Molnar’s source work Lent Mouvement Giratoire (1957-2013), Reas completed the trajectories of Molnar’s 1% disordered sections of Dürer’s invisible square, giving life to an otherwise static work.

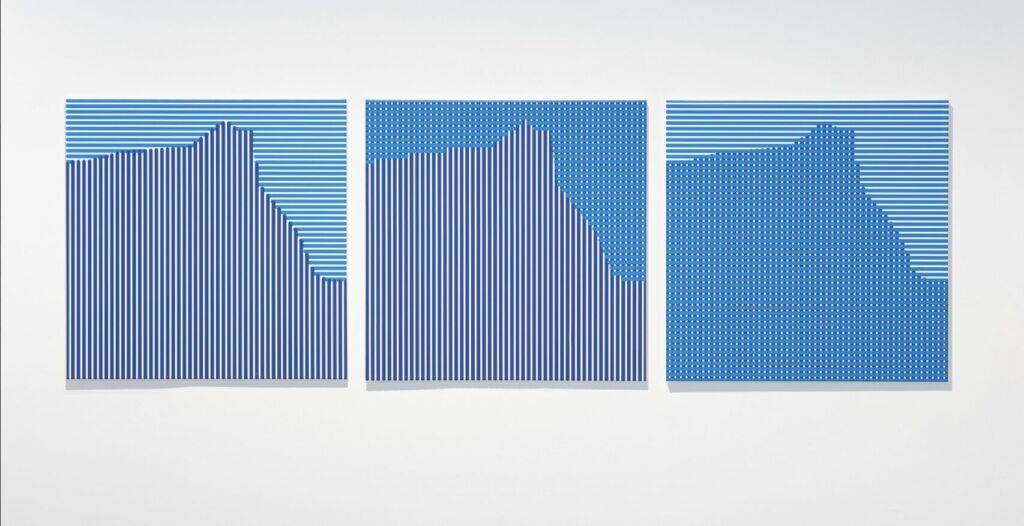

The various homages in the exhibit, whilst all relatively simple in concept and execution, take on multiple and varied forms. This selection not only accurately reflects Molnar’s ability to achieve density within simplicity, but it also creates a varied and engaging exhibition whilst avoiding museum fatigue. In addition to the selection of raw material, there are also clever curatorial flares in the hang, which recall the bridges of Budapest and Vera’s temporally bungee-roped life’s work.

By placing the work of the 85-year-old Frieder Nake, a close friend and colleague of Molnar’s, next to the homage by Reas, a young and well-known artist of the new generation, Máté and Castelli are inviting the viewer to see the differences, or perhaps the lack thereof, in the works of two of Molnar’s admirers of different generations. The result may be surprising…

À La Recherche de Vera Molnar is a subtle yet bold exhibition that recalls the best of a classic museum hang with simplicity in the context of a tech narrative. The joining of two tales, that of a woman’s life and work and the development of technology, draws out an elegant approach to the subject of digital art and societal changes. The admittance, too, that previous generations can – and perhaps should – be considered relevant and even admirable goes against much of the spiel that contemporary artists and exhibitions are offering up nowadays, a push-back that is welcomed by this author.

What remains untold in À La Recherche de Vera Molnar is the narrative of a woman who was just that, a woman in worlds that belonged to men. Whilst, as Máté correctly states, the fact that Vera was a woman was not her main focus. In fact, she would tell us, ‘I considered myself to be François Molnar’s cook until his death, and I was content’; it remains something that is important, even in its unimportance to the artist. Perhaps this subject of Molnar’s woman-ness was the 1% of disorder integrated by the curators in an otherwise seamless exhibition…