Words by Maren Häußermann

Change the system—materials, production, consumption. We can make it better. Sustainability. Quality. Democracy. Inclusion. These words are behind the concept of the creations of fashion design students in Austria. Turn it around and inside out. Go back from the customer to the pure fabric. The individual body is in the center, the material covering it growing and spinning into form.

In the Lab is the name of the project series that makes the idea of change tangible. The University of Art and Design students in Linz who study the Fashion and Technology course dive deep into what we know as fashion. They look behind the design, search for new ways to present it, and materials with which to realise it.

During the first presentation of In the Lab at the Ars Electronica Center in Linz, Vogue Germany noticed the six current projects. On its 40th anniversary, in September 2019, the magazine exhibited the students’ works in Munich. They then moved on to show their innovative ideas at a fair in Tokyo in February 2020. An invitation to the Dubai Expo in October 2020 followed. Covid-19 is the reason for a one-year postponement of this event.

When Belinda Winkler walks into a clothing store and sees the low prices, it frustrates her. The fast-fashion system of a globalised society lures consumers with special offers. They do not question the 5 euro price tag at the jeans they like.

But Winkler knows that manufacturing trousers can never cost less than 5 euros. Winkler knows all about the creation and production of clothes and the work behind it. The work that most of consumers do not see. That is why consumers mostly do not ask about the origin of the fiber. Or about the technology that made it into a fabric. They do not think about the ideas and thought processes regarding the design or all the individual production steps.

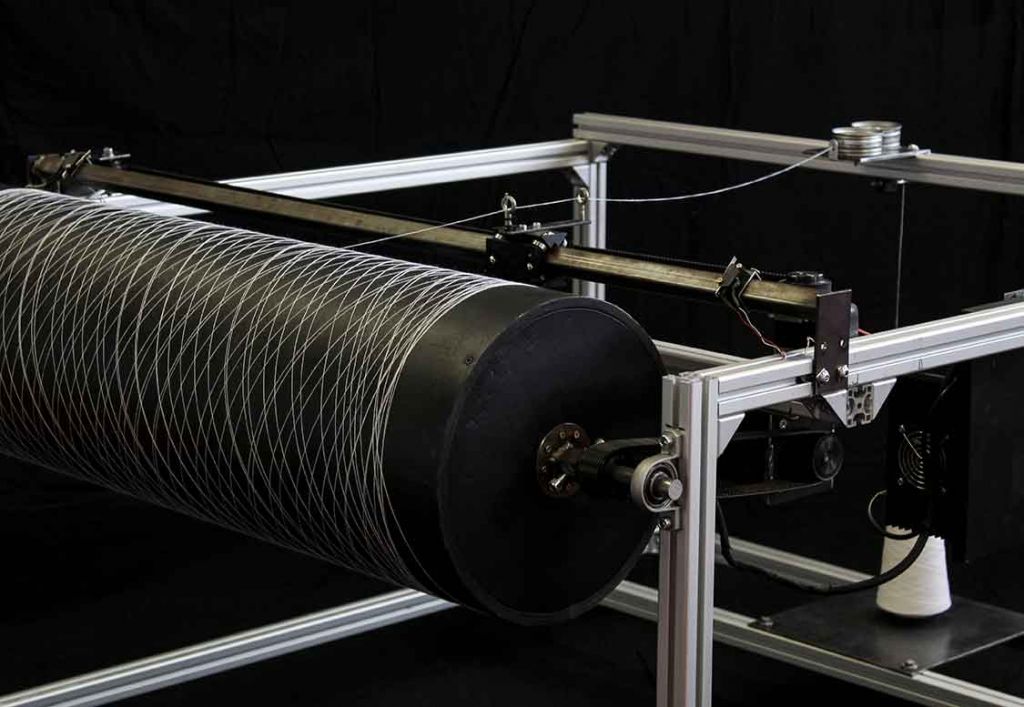

The 26-year-old designer Belinda Winkler was working on the spinning wheel when she suddenly noticed something. The first layers of yarn she had been winding on the spool already looked like a piece of fabric. In a double helix structure, Winkler had been wrapping the fibre around the bobbin. Now, the crossing yarns looked like a cloth she was expecting to only produce in the next steps.

Usually, creating a piece of fabric is a long process. First, one must put the yarns into the weaving or knitting machine. The threads lay next to each other, stretched in between two beams. In the middle of this carpet of fibres sits the comb. It splits them so that every second one is either up or down. Then, a needle shoots in from the side and through the divide. Afterwards, the comb switches the position so that the yarns change place and go either up or down. The needle shoots back. In this way, the machine creates a pattern of crossing fibres. The outcome of this process is a two-dimensional fabric.

If you hold a piece of fabric in your hands, you do not see that it consists of a lot of crossing yarns. The pattern is too compressed, Winkler explains. She wants to make this pattern, and thereby the whole process, visible. That is why Winkler does not tighten the yarns. Together with a mechatronics engineer, Winkler developed a new winding machine.

The technology is not new. It is being used in construction to create specific building components. The form of her final material depends on the body of the spool. It is three-dimensional and for now, round. I can only produce tubes. But theoretically, if I change the spool, I can have bulbous forms or cylinders, too, says Winkler.

Usually, the work only starts with the fabric. In the next step, one has to think about the design, cut the two-dimensional material, and sew the parts together. Winkler found a way to eliminate all these additional steps. She has already created a whole piece of clothes in just one step. The design comes fully fashioned out of the machine and entails fewer production and transportation costs or waste.

Winkler says that, if further developed, it could be possible to have a robot spin the product. Then, the production would be similar to a 3D print. Winkler can think of machine-producing clothes in three different sizes in industrial production. However, it would also be possible to customise the spool as needed. Her priorities are that the machine produces clothes alone and that the yarn falls naturally and individually into place.

Winkler plans on further investigating the characteristics of the yarns. For this project, she experiments with different kinds of fibers. On a regular spooling machine, she tests how thick the layers have to be and how the characteristics of yarns influence the outcome. Smooth threads will make a fragile fabric. Elastic yarns, on the other hand, will give it a compact form. The product can be loose, long, or stiff. Adding foam to the body helps change the size.

Usually, the process ends with the judgment of the customer. Why not turn it around and start here? What do people need and want? That is what Simon Hochleitner asked himself. In the second semester of his studies, he learned how to use the Clo3D software. With this, one can change the two-dimensional designs virtually and sew them together like this as well.

One can then fit the piece of clothing to a three-dimensional avatar and have a look at the final product in a digital form. Hochleitner used a 3D scan of his own body to experiment with. Then, he went back from his body to the design. His project became about reconstructing two-dimensional patterns on three-dimensional virtual bodies and deconstructing these bodies to get back to a two-dimensional form.

Create a body first, any body. Hochleitner worked together in an interdisciplinary team and thus found himself no longer programming with software for fashion creation but with the software used in architecture, product design, and game design. The bodies stopped having a human form. Together with his colleagues, Hochleitner experimented with the codes, and changed the sizes and the shape of his virtual model.

At some point, I stopped seeing the body as an object to be dressed, Hochleitner says. Instead, he focussed on seeing it as the origin of the process. No two bodies are the same. Hochleitner soon saw that in the two-dimensional designs, the output of the process. I never get symmetric patterns because the human body is not symmetric, he says.

A digital body is composed of various small fields that are connected. They have edges, and so the final design pattern has edges. Other than the big fashion houses, Hochleitner works with very exact scans. His aim is not to have a pretty end product but to have a design pattern that depicts the body accurately. At this point, he stopped to look at the standardised measuring system. Instead, he found a way to custom the size and form of the design and create clothes that fit perfectly.

Everyone who wants to study with us needs to want and change something, says Ute Ploier, one of the two chairs of the Fashion & Technology course. Ploier’s research focuses on the new dimensions of fashion and follows the idea of creating unique physicality. The main criteria for admission is an open mind about everything, the design, the production, and the fashion presentation.

This means the students must create their first fabric in the second semester. This can be banana peels, ceramic, ice, or whatever the experiments generate. In the second step, they must use this fabric to design and produce a piece of clothing. The investigation of the material is at the centre of this process. Its characteristics. How can its nature be used to create a three-dimensional form? Can it be grown?

Apart from the basics in fashion design, the students learn about robotics, 3D printing, simulation technology, and how to work with biomaterials. At the same time, they get to experiment with traditional production craft, like weaving, knitting, and draping techniques. The students need to know how fashion works. From there, the aim is to find something that can be changed and find an innovative solution to accomplish this.

It is almost impossible to produce completely sustainable garments, says Ploier. But now, during a global sanitary crisis and the lookdown of various economies, we see that a lot is possible that we would not have thought of before. We are used to exchanging clothes regularly. The economy needs this consumer behaviour. Jeans have predetermined breaking points so that, sooner or later, they will have to be replaced. Ploier hopes that with new technology, we can reduce production and focus again on quality rather than quantity. The production of high-quality clothes will be more expensive, but they will also stay alive much longer.

How can we produce more clothes locally? For this, we need resources and ways to cut costs and pollution. Creating new fabrics that allow this development to happen requires creativity, brainstorming, and experimenting with wild ideas. Why not use liquid materials like clue and shaving creams to create three-dimensional, organic structures similar to lace?

Why not, for example, grow bacteria, feed, and nurture them until they produce cellulose? This is yet another one of the six projects of the series In the Lab. The idea is not new; fabric from cellulose has been created already. Working with bacteria has some promising advantages to it. They need much less water than, for example, cotton plants, no pesticides, and the Petri dishes can be pilled.

The current system is not fair. It exploits resources, human beings, and even gender standards. The students in Linz want to change this by making the process of fashion creation visible. In the Lab allows the audience to see first-hand how one develops materials and how they influence the design and vice versa. The students do not just study the creation of garments; they question it. With their experiments, they go beyond fashion. In the Lab gets international attention now. COVID made persistent problems visible. And the chances are that the combination of Fashion and Technology will make the change happen.