Text by Nicholas Burman

For as long as digital technologies have existed, they’ve been a means through which sex and desire have been filtered and fed back to us. In the increasingly networked, ‘smart’ society in which we live, the exact relationship between what we want, why we want it and how we satisfy our desires is more often than not mediated through algorithms, digital interfaces and artificial intelligence-driven hardware.

Alfie Bown’s Dream Lovers is an essential and critical account of this new digital architecture and its effects. Touching on the economics of Grindr, VR porn, the gamification of social interactions, and much more, it offers both a broad overview of the political forces behind this unfolding revolution and also provides those of us surrounded by digital prodding an opportunity to critically reflect on the tech that shapes the quotidian. Importantly, Bown also imagines how this technology could be used for progressive means.

Bown’s ongoing interest with video games and ‘gamification’ underpins this book. His divorce also had an impact. Discussing his subsequent experimentation with an AI girlfriend and a virtual reality relationship simulator during our screen-mediated chat, he clarifies that: “I wasn’t seriously going to try and replace my wife, Black Mirror-style, with a robot, but a lot of things had changed in the realm of love and digital media since I’d last been single, and I wanted to see how they work psychologically.”

Bown is not the first writer to take a look at these topics. Sex robots, in particular, have garnered much interest. Barak Lurie’s Rise Of The Sex Machines (2019) is one ludicrously reactionary discussion of the topic. Meanwhile, Kate Devlin has supplied a much more historically rooted and lucid account in her 2018 book Turned On. By placing this discourse within an anti-capitalist stance, Dream Lovers is a more radical project than many of its thematic predecessors.

I asked Bown about why he uses ‘gamification’ and why a term such as ‘commodification’ isn’t sufficient at the present juncture: In a sense, I am talking about commodification, which has a history as long as capitalism itself. But gamification is a way of thinking about the ways in which we’re programmed and reprogrammed to be capitalist subjects in this particular moment in history. Bown sees this ‘programming’ taking place primarily through rewards systems built into gamified systems that are designed to edit people’s patterns of habit.

Dream Lovers isn’t solely autoethnography. As discussed, it brings broader political struggles into the mix. And while discussing dating apps, for example, Bown draws on journalism by Evan Moffitt, who has written about how Grindr has transformed parts of gay cultural life. Bown says: Whole communities of people are meeting up via Grindr but staying on their phones the whole time because they’re accumulating kudos through the app. Grindr has digitally augmented the experience of dating and sex.

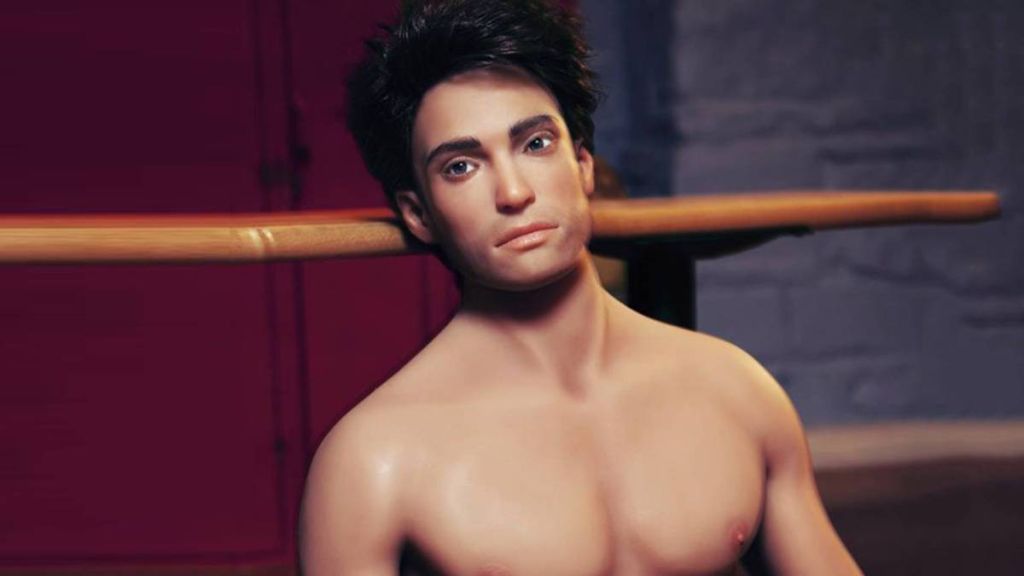

Right: An iteration of Henry from 2019, a male-bodied AI sex robot by RealBotix.

The China-based Kunlun Tech Co bought Grindr before Trump made it a matter of national security to bring it back under ownership by a US company. As well as sinophobia, this furore was also about a concern over who has access to what intimate data. Bown explains that intimate data describes what you want, when you want it, and where you are when you do. Ultimately, “what it creates is a way for your behaviour patterns to be edited.”

Online retail giant Alibaba has been putting such insights to use in Hangzhou, one of many historical cities which is being overlayed with an AI-fuelled ‘smart’ one. While visiting Hangzhou, Bown was presented with an Alibaba car that will predict when you’ll be hungry and what you’ll want to eat and will automatically suggest it to you. This predicting and steering of desire isn’t solely for the benefit of the user. The car will take individuals to establishments that use Alibaba’s payment system. In such a vehicle, it will seem like a pre-existing desire is being met, but in fact, a new one is being cultivated – for the benefit of Alibaba’s profit margin. In the 21st century, data is not only describing the world as it is; it is employed by vested interests to change it. Smart city infrastructure in Silicon Valley and elsewhere is attempting the same thing.

This conceptual pivot from data as describing something that has happened to something that shapes the future is central to Bown’s critique. When data becomes enshrined within an algorithm, it then becomes ossified in the system. Algorithms only work out what’s best overall, so the person who has slightly different desires is parcelled off and those people are pushed into the more normative actions. What we need to think about is the power of data as an excuse for corporations to claim diminished responsibility, but more importantly, we are creating programmes that set a new future, and we’re more likely to follow that pattern than if these systems hadn’t been built. This should be a major concern for those wanting to construct new value systems and ideological outlooks. Progressives, feminists and anti-racists need to be involved in conversations about what algorithms we’re making because they’re going to set the tone for how we act in the future.

Bown draws on psychoanalysis considerably throughout the book. He says this is because capitalism itself has become more interested in desires and sex drives, two major points of interest for the field. “I’m more Lacanian than any other form because Lacan was interested in politicising questions of psychoanalysis.” Bown highlights Lacan’s distinction between instinct and drive. For Lacan, instinct refers to wanting to eat or have sex, for example. Meanwhile, drives may feel like instincts, but they are, in fact, socially motivated. Wanting to buy a particular type of trainer or fancying a specific person’s dating app profile, for example, are examples of drives. What is instinctual and what drives our behaviour are different.

If instinct and drive are different, are desire and love also distinct? What interested me was that there are similarities between them. The way we search for a new lover with digital technology is very similar to how we find a Pikachu on Pokémon GO or search for noodles on Deliveroo. The content of those experiences is different, but the structures are the same. I was really surprised to find that Freud already discussed this. He says that it’s not an accident that we use the word ‘love’ towards vastly different things in casual discourse, such as a new piece of clothing or a partner. He says it’s because, at a structural level, there are similarities between how we feel about these things and the role they play in our lives. We like to think that love is something special, but there are similarities between these things in our lives because of what structures our desire for them.

Right: A pile of e-waste in England. 20 to 50 million metric tons of such waste are discarded each year globally. The west sends much of its waste to Southeast Asia. Image: Stefan Czapski, courtesy Geograph.

I

ask him about why desire has become a prominent topic in recent years. Bown says: “It’s worth thinking about the last decade or so of politics. Starting with Obama, there was a lot of libidinal desire driven through the slogan ‘yes we can.’ His 2008 election was really the first digital one; it tapped into peoples’ libidinal, emotional energy. Since then, we’ve had Trump and the Cambridge Analytica scandal, which have brought to light the way in which politics can attempt to ‘nudge’ us in very negative ways.” Once again, for Bown, this situation returns us to questions around involvement and agency. We have to decide how we use this revolution in desire to our advantage, rather than to the advantage of corporations.

What often goes missing in conversations around the ethics of software and computing is how the hardware is produced. Given his background, Bown tackles this issue through video games. “Inside every console is a footprint of international capitalism,” one that is driven by low wages and poor conditions in the global south and exploitative of minorities. This takes place while representation of minority groups within video games increases [1], a situation that highlights the difference between structural desire and desire as it is represented. “Working out how to produce things ethically is as important as ecological questions. For example, I’m really interested in permacomputing, because planned obsolescence is one of the great evils of our time.”

I voice some scepticism as to the potential for any tech ‘solutions’ to love or desire to be anything other than experienced as simulacra. Bown responds: I don’t think that tech will act as successful replacements for ‘real’ sex, shall we say. It’s more that, even if they only perform 40% of that function, that’s still an enormous amount of power. I don’t think that they’re always simulacra, necessarily. And even if it’s just a simulacrum, it can still have an enormous impact on your life. The difference between real and digital there isn’t an issue that has to be solved.

He still holds an optimism from the early days of the utopian internet, where it was imagined that it would usher in a new age of a digital commons for everyone everywhere. His optimism is also visible in Dream Lovers, which presents a series of intriguing alternative applications to current technology. One is reappropriating the Fitbit to track workers’ health while at work and holding employers accountable for the negative health consequences of the tasks they get their employees to do or how they treat them.

Despite the popular imagination about what revolutions entail, most major changes to everyday life take place slowly and may not even be perceived. We may wake up and find ourselves living in the smart city of the future, unaware of how our desires have changed over time. A quote in Dream Lovers from Georges Perec is a poetic reminder to always be aware of the everyday and to remain critical of it:

What’s really going on, what we’re experiencing […] How should we take account of, question, describe what happens every day and recurs […]? To question the habitual. But that’s just it, we’re habituated to it.

At the heart of Dream Lovers is the imperative for us to engage with the technologies and systems with which we are constantly becoming habituated.