Text by Lyndsey Walsh

Whether it be in flocks of birds, schoolings of fish or even herds of mammals, individuals who come together seem to find power through acts of collective behaviour and grouping. This is the central idea behind the phenomenon of swarming, which refers to a collective motion of individual agents, self-propelled entities and living organisms.

While swarming is prevalent throughout different living systems, it also has become a crucially important concept for the expanding discourse in technological sciences in relation to the role it is intended to play in biomedicine, robotics and research on intelligence and self-organizing systems.

This intersection between the so-called “natural” and technological has laid the groundwork for Art Laboratory Berlin’s exhibition Swarms, Robots and Postnature, curated by Art Laboratory Berlin co-directors Regine Rapp and Christian de Lutz. The exhibition features the work of Käthe Wenzel, So Kanno and Sofia Crespo and explores how swarming gives way to an interface between the biological and the machine. The exhibition as a whole uses these three artistic viewpoints to surface questions about traditional notions affiliated with what is seen as “natural” while also giving shape to create visions of a still-forming postnatural world.

From Wenzel’s work Bone Bots to Kanno’s Lasermice dyad to Crespo’s Neural Zoo, these artists highlight how the technological and the biological are entangled in a massive web of interactions. However, I find that the exhibition does more than point the lens at these creative explorations of swarming. In the exhibition’s accompanying artist talks, the artists dive into their material processes and expand upon ideas about how we perceive these actions in living and non-living systems.

In Wenzel’s work, this primarily focuses on notions of mass consumption, while in Kanno’s work, these ideas play a considerable role in the multi-sensory aesthetics of Lasermice dyad. Crespo follows suit by posing a series of questions about why computer-generated forms might appear as beautiful: if this is beauty within the dataset itself, or does this aesthetic impression come from somewhere else?

In terms of aesthetics, swarming represents a type of awe-inspiring feeling towards a magnitude that can easily be connected to Immanuel Kant’s discourse on the sublime. This massive power, movement, and presence may draw people to ideas and notions of swarming and try to recreate them in technological applications. But, much like in Crespo’s work, there is a particular, desirable, and unsettling type of beauty associated with these overpoweringly massive moving swarms.

While the sublime has been used to refer to a connection between rationality and emotions in the Romantic period, its aesthetic connotations often refer to aesthetic judgements on nature and dissonance between the natural world and the human one [1].

Throughout the Romantic period, this sense of dissonance is often depicted as being overcome by implementing acts of human freedom that transcend the laws of nature. However, this boundary between human and nature, biological and machine, has become increasingly permeable, which leads me to wonder how the sublime can be considered in the postnatural world of swarming robots and nanoparticles.

Crespo’s Neural Zoo in the exhibition speaks to the connection between aesthetics, patterns, and massings that almost gives a technological take on the natural sublime. The series recombines known elements and forms of living organisms to create visions of novel entities that rearrange nature.

These visions are created from the datasets that Crespo works with that correspond to various species and living entities’ morphologies. In contrast to the sublimes reference to the power of nature, Crespo’s work exposes how computers see images and extensive datasets to recognize and create high-level features that give visual and aesthetic power to their composition, thus giving aesthetic power to the technology that, in turn, disrupts the orderliness of the “natural”.

Comparatively, Wenzel’s Bone Bots and Bone Costumes unsettles this boundary between the biological and the machine from an entirely different aesthetic direction. The uncanny sight of re-animated bones fused with moving machinery highlights the collective and creative power of amassing materials into new forms. This use of the uncanny also helps to prompt the audience to consider the ethical issues around mass-exploitation and consumption when it comes to the bodies and remains of living organisms. Wenzel discloses that she only uses “leftovers” of animal bodies and parts that would end up being thrown away otherwise in her artist talk. While these hybrids of bones, fashion and machines embody a sense of playfulness, they also seemed to be possessed by recognisable presence. The Bone Bots will waddle, scoot and teeter with a haunting but adorable swagger.

These intersections between the so-called “natural” world and the technoscientific world have come up repeatedly in countless transdisciplinary discussions. Swarming has also found a place in these critical discourses. For example, in the Serpentine Galleries’ program The Shape of a Circle in the Mind of a Fish: we have never been one, swarming is conceptually framed as a critique on modern notions of individuality, which suggests that these groups may speak to the sheer largeness of networks and how events often are brought about by countless interrelated agents.

In some sense, I find this to be undeniably true. It can be nearly impossible to dissect individual roles in complex interacting systems, living or otherwise. This can be seen with beehives and other swarming insects, where it is not always true that the queen of the hive truly is the one that dictates the actions of the group.

However, this complexity also offers new ways to understand and think about intelligence with swarming concepts like emergence, which refers to the existence of self-organizing systems that exist regardless of a hierarchical control system, as well as stigmergy, which refers to the coordination of actions and between agents that occur through indirect means. For swarming, it seems that a special kind of intelligence exists without clearly understood order and control, making it difficult to quantify and describe when observed in biological systems concretely.

In the laboratory, swarm intelligence has become a highly desirable trait in research and in developing robotics, Artificial Intelligence and nanoparticles. In laboratories such as the Hauert Lab at the University of Bristol, these technological entities are created to study how swarming works in living systems and bring new types of swarming robots to life.

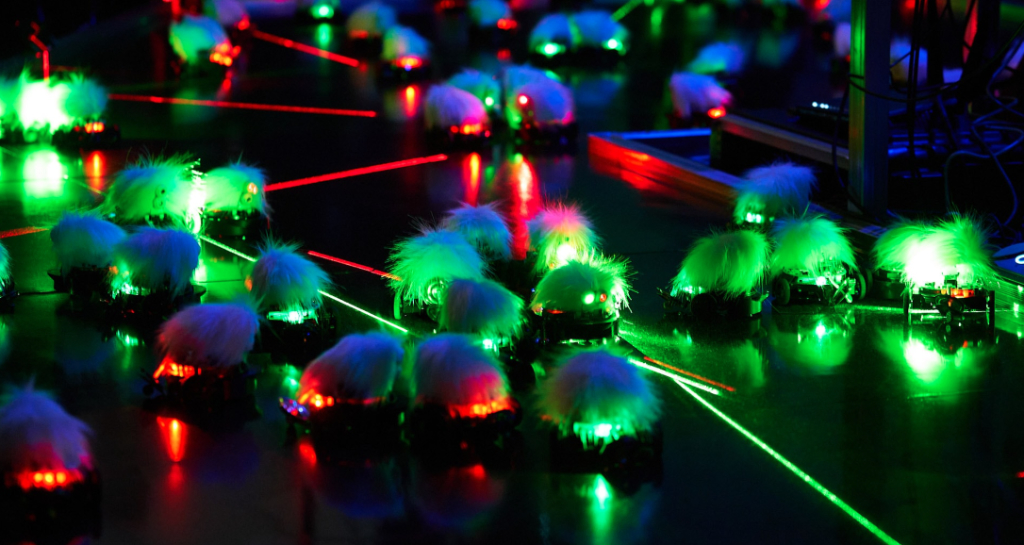

Kanno’s creative exploration of swarming robots in Lasermice dyad complements these laboratory investigations. While swarm networks are naturally occurring in many different groups of living organisms and being re-created in the laboratory, the logistics of these interactions often remain invisible or imperceptible in real-time.

Each of Kanno’s moving devices has a light detector, a laser and a solenoid, and a patch of white “fur”, which is used to diffuse the light emitted from the other robots’ lasers. When triggered, the robot will light up either red or green and perform a corresponding type of movement behaviour. These collective behaviours are then given an auditory rhythm through the sound of the robots’ solenoids hitting the floor.

Kanno’s work invokes questions about how humans perceive and recognize intelligence, connectivity and interactions in non-human entities, which I believe is crucial when considering the promising potential uses of swarming robots, especially considering that these perceptions can be driving factors in the design of swarming robots.

The ability to create technological, self-organizing systems similar to living systems and can coordinate improvised and systematic actions in response to specific cues could radically change how technology can be implemented in areas like cancer research, farming, and more.

Swarming robots could make difficult tasks easier and impossible feats of small and large-scale actions possible through the power of the collective, such as non-invasively targeting tumour cells for cancer treatments or cleaning up a large, polluted body of water. Thus, massive acts of collective behaviour directed by human design have many appeals.

However, I find that these promising technoscientific potentials can also raise important questions about the postnatural future by asking who is responsible for the actions performed by the collective. While swarming robots could work collectively to carry out particular types of swarm intelligence-directed decision-making, what happens when those decisions go against their intended design or act in opposition to the desires of their creators?

These are questions that I find Art Laboratory Berlin’s Swarms, Robots and Postnature circles back on repeatedly in exploring the artists’ own experiences of their artworks. While co-creation is a recurring theme in the exhibition, each artist has their own approach, conflict, and understanding with these interacting systems.

While sometimes the swarms are seen as unpredictable and out of control, there is a great level of empathy directed toward understanding how they perceive the world around them. In the end, there might not be a singular answer to these questions but a need for a continuing investigation into how we are all connected in complex webs of interactions. Regardless, the writhing bodies of the masses, both biological and robotic, will continue to swarm, mesmerize and give shape to an ever-changing postnatural world.