Text by Hannah Scott

A pig, canonically pink and adorably miniature, stands on a rubberized mat. It sniffs around, snout twitching, then locks eyes with the camera’s lens. Admittedly, I haven’t met the gazes of many pigs, city dweller that I am, but I swear there’s something so familiar about this one’s stare. “This is a humanized pig,” a tenor’s voice confirms authoritatively, in apparent affirmation of my pang of recognition.

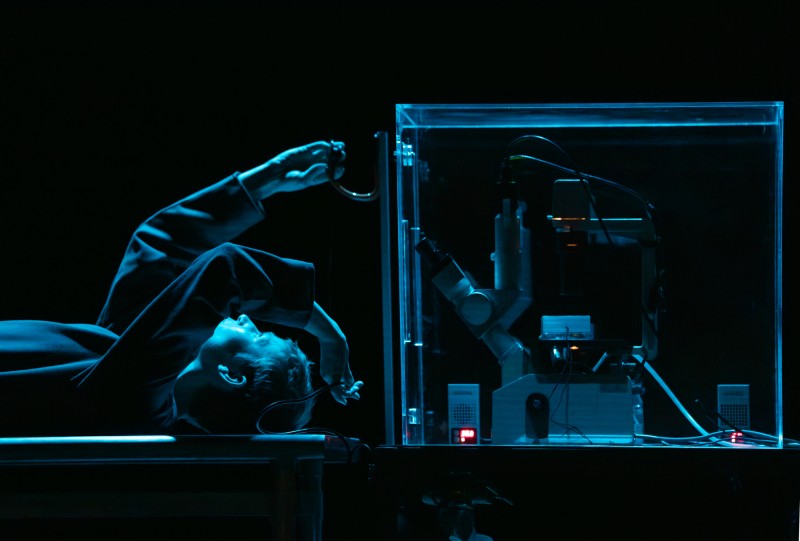

This “humanized” pig lives in a laboratory outside Munich, where it is a subject of xenotransplantation research — a field of study aimed at genetically modifying animals to produce human-compatible cells, tissues, and organs (in this case, hearts). In Xeno In Vivo (2024), a multimedia performance spanning live opera, an original score, documentary film, and ceramic sculpture that premiered at the Exploratorium in San Francisco, artist Heather Dewey-Hagborg bears witness to the clinically fleshy world of the xenotransplantation lab (farm?). Thousands of clones everyday, the quartet bellows as the documentary projected behind them flashes images of pigs being measured, injected, and petted by their human handlers.

Three types of characters animate this multidimensional narrative: the genetically modified “donor” pigs featured in the video documentary, the scientists whom Dewey-Hagborg interviewed (and whose personae are adopted by the singers), and Dewey-Hagborg herself, playing the role of documentarian and narrator, describing and asking questions about her experiences in the lab. In the opening movement of the opera’s libretto, a dialogic exchange transpires between the artist and the chorus of scientists: Pig 3.0 — does it look different? Dewey-Hagborg asks. It does not, the chorus replies.

Through these operatic utterances we glean something of the beliefs and values held, explicitly or implicitly, by the scientists in the lab in Munich. Archetypical renderings of science in popular media tend to situate it in the realm of the objective, detached from the individuals who practice it. Dewey-Hagborg’s scientists, however, speak (or rather sing) for themselves.

For instance, in the third movement of the performance, titled Nature? The zooarchaeologist-soprano intones: domestication is genetic modification / the difference is the intensity. This line refers to the 10,000-year history of selective breeding, a process by which humans tipped the scales of evolution to produce the pigs we know today from wild boars by gradually selecting for desirable porcine traits over generations.

The film’s close-ups of ancient Greek vessels depicting half-man-half-boar creatures and shots of fossils meticulously arranged and tagged with their Latin signifiers uncover a deep history of hybridization and human interventions within it. Throughout Xeno in Vivo, the scientists position CRISPR-enabled gene editing within this aeons-old history of selective breeding — the only mutation, they posit, is the speed at which evolution occurs.

But the same scientists would also point out how groundbreaking and new what they were doing actually was, Dewey-Hagborg noted when she and I spoke. The central question coursing through the performance probes this vacillation, asking whether engineering animals to be more human represents a process of authoring life anew or of reconnecting both ends of the thread of evolution.

It’s not that this vacillation is necessarily nefarious; after all, each pig will donate multiple organs, maybe helping a million people, the geneticist character points out. Rather, on a slightly more abstracted level, Xeno in Vivo asks how the language, metaphors, imagery, and references scientists use to communicate their intellectual projects shape what we know about the world.

The third lens through which the audience gains access to xenotransplantation is the one adopted by Dewey-Hagborg herself. As a documentarian capturing footage of the lab and interviewing scientists, Dewey-Hagborg occupies a relationship to the research that differs from those she dons in her previous creative inquiries into frontier science. In the artist’s previous biologically inclined projects, making art tends to look a lot like doing science.

In 2019’s Lovesick [1], for instance, Dewey-Hagborg worked with biotechnology company Inter Genesis to design and produce a retrovirus that promotes the production of oxytocin in those infected by it. Here, however, Dewey-Hagborg’s primary role is that of an observer (due in part to the highly restricted nature of this experimental strain of research).

Dewey-Hagborg’s observer isn’t appealing to Objectivity; the artist still invites subjectivity to guide and colour her movements through the lab and the questions and associations she draws. There’s a moment in Xeno in Vivo when our guide announces she’s going to take a walk in the woods. The chorus goes quiet, and the score’s steady pulse softens. A shadowy creature emerges on the projection surface, ambling about in the dimly lit grain of a video captured in low light. Not at first, but eventually, the creature’s identity comes into focus as a wild boar, which Dewey-Hagborg encountered in the forests surrounding the Munich laboratory.

Confronted with the alienness of this wild boar in contrast to the docility of the lab pigs, which have nevertheless been altered by human hands, the degrees of difference between self and other become confused. The term xenotransplantation literally describes the integration of two entities which are alien to each other, yet scientists only needed to modify 69 genes [2] to produce a minimally viable porcine kidney.

Indeed, the scientists remark that the xeno pig heart is visually indistinguishable from a human one. Are we losing some important sense of otherness, of relating across differences, if we can produce chimerical combinations of different organisms? Or are we collapsing some historically produced, conceptually contingent divide between lifeforms, entering into a harmonious soup of oneness?

The second time I saw Xeno in Vivo performed live was during the annual SynBioBeta conference in San Jose, California, which convenes scientists, entrepreneurs, designers, and enthusiasts to champion synthetic biology into the future. Not quite an industry expo and not quite an academic poster presentation, SynBioBeta has a distinctly summer camp air about it (amplified by 80° F weather in early May). As part of an evening event dubbed “Parables for the Biotech Age,” [3] Dewey-Hagborg and the chorus of opera singers performed a stripped-down version of the original work in an IMAX dome.

With the conference’s sunny disposition toward the future in my mind, the two renderings of the hybrid pigs that Dewey-Hagborg produced for Xeno in Vivo became even more potent in this second viewing. In one of these images, animated 3D models portray pigs bearing stripes and spots — a look into a parallel project undertaken by the Ludwig Maximilians Universität lab in Munich that seeks to produce pigs that look different. These images echoed the aesthetics deployed by the synthetic biology startups’ presentations I had seen in the conference hall — rotating models of proteins ablaze in neon, animated helixes receiving Cas9 nucleases.

The other representation takes the form of 3D-printed ceramic sculptures of pigs, composed of disparate yet interchangeable parts that connect. This interoperability references one of synthetic biology’s main projects — to reverse engineer biology by breaking it down into interchangeable, interoperable parts. In the video, a change in environment transports us to a beach where Dewey-Hagborg shovels sand.

The clay pigs, outfitted with their component parts, are then buried and engulfed in flames to fix their final form. This ritual endows the story of xenotransplantation with a feeling of importance, even sacredness — a tone that breaks from the narrative stylings of the scientists, who appear inclined to normalize their project, to naturalize it within a broader, disembodied history of evolution.

Xeno in Vivo isn’t interested in telling its audience how to feel about genetic engineering. Instead, the performance succeeds in bringing its audience into the network of equipment, subjects of inquiry, ideas, and people who make up the process of doing science. Weaving this web opens up different points of entry for thinking about increasingly hybrid futures, not only for lay people like myself but also, I imagine, for scientists. Dewey-Hagborg admits she finds it exciting to think about creating new species. She just thinks there should be a lot more stories about what it means to be able to do these things. We need both the speculative 3D models and the clay sculptures, the chimaeras and the rituals.