Words by Professor Andy Miah

While drones are in the news on a near-daily basis, their use within artistic practice is a lot less well known. Yet, drones have become a platform for creative, innovative, and disruptive artists for nearly 10 years now and have played a crucial part in constituting the most amazing examples of drone applications we see around us in the world today.

Some of their earliest experiments have gone fully mainstream already, but they started off as creative, innovative experiments, drawing together experts in technology, digital, and artistic practice. For instance, experimental swarm systems were pioneered by the Ars Electronica Future Lab and led to the creation of large scale drone choreographies, showcased on the world’s biggest stages, such as the PyeongChang Olympic Winter Games in 2018 [1].

At the same time, creative technology collective Marshmallow Laser Feast began experimenting with drone performances. In 2012, they presented what remains their most accomplished drone performance named ‘Meet Your Creator’ at a time when drones were not even available on the high street [2].

MLF’s theatrical use of drones positioned the technology as a new kind of artificially intelligent performance artist, inspiring many other artists to think of the drone in similar terms, such as the Elevenplay×Rhizomatiks performance, Dance with Drones, from 2014 [3]. Alternatively, experimental film director Liam Young has made movies shot entirely by drones [4] and created his own line of drone couture, which performed as floating backing dancers to a John Cale drone show at London’s Barbican in 2014 [5].

These initial experiments first framed the drone as a new medium in the artist’s sandpit, pioneering not just the utilisation of the drone but the interconnected specialities that drone flight required, from creating 360 cameras to coding spatial arrangements in three dimensions. Some of the world’s best robotics engineers were working with the arts sector to bring the many remarkable capacities of drones to the public’s attention. For instance, the Swiss renowned ETH Zurich engineer Rafael D’Andrea worked with Cirque du Soleil to create SPARKED, a short narrative film demonstrating the potential of gesture-based drone control, and, as yet, unrealised consumer function [6].

When the consumer drone took off as a major household item in 2014, it spawned a generation of new amateur drone artists, whose emerging skills as filmmakers brought new perspectives on the world, from flights inside volcanoes to the emergence of the ‘dronie’ as the iconic staging shot of a drone pilot – like a selfie, but shot by a drone [7].

These populations grew quickly into establishing new formats in film, with drone film festivals popping up all over the world. By now, choreographers, photographers, filmmakers, musicians, and performers have each employed drones to explore their creative potential in a way that speaks to a much wider history of artistic innovation that can be traced across the centuries. These early pioneers have disrupted a whole range of existing creative practices. For example, drone swarm choreographies signal the end of fireworks display as we have known them as drones can now beautifully emulate their aerial display [8].

Even Disney is considering replacing its evening firework display with a drone display instead, most likely creating enormous 3D visualisations of their most popular characters [9].

But perhaps most fascinating is how drone artists have also engaged us with the idea that the human use of technology has ushered in a new, disruptive force in the natural order. Drones are flown above us, enjoying a God-like perspective on the world. It’s a suitable metaphor for a time in which non-human biology and technology seem to exceed the human species’ power as viruses and robots become all-powerful.

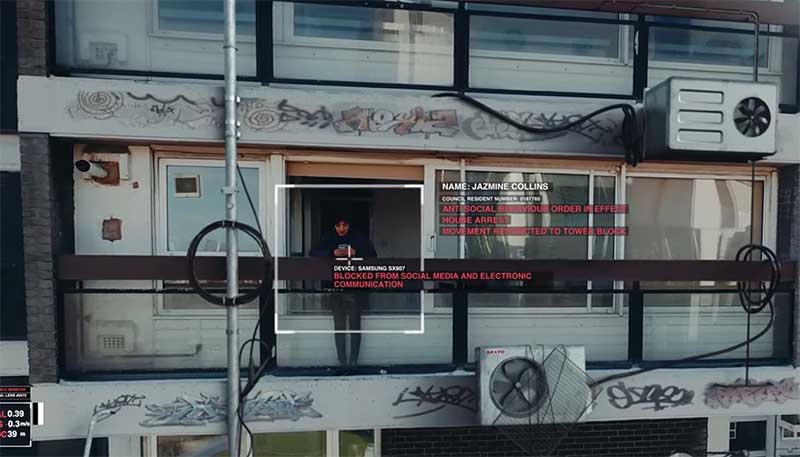

Other artists have sought to engage us with the political history of drones by direct and explicit references to such behaviours within their artwork. Notably, James Bridle’s Under the Shadow of the Drone (2012) [10] engages us with the idea that drones are all around us, infiltrating our lives, even if we do not see them. It consists of single-line drawings depicting what he describes as the ‘canonical’ drone – the shape of the US Predator drone – an image which became popularised as the destructive machines used in military missions. Bridle used white tape laid out on the ground in a public space to create a life-size outline of the drone’s shape. The outline resembles the classical manner in which police would outline a dead body at a crime scene with chalk to provide the trace of the person after the body has been removed.

In doing so, Bridle’s art directly confronts the political activities of predatory drones – and the US Predator drone in particular – speaking to the blurred territory of art and activism. His work drew attention to how drones inhabit the spaces where people live, even if they do not notice them. These vehicles pass by our homes on their way to commit some destructive act.

Bridle’s work also inquires into how we may understand the drone as a new node within our digital society. In this respect, his Shadows alert us to the idea that the network is not just all around us, it is also mobile and capable of moving across space and time, infiltrating areas of the world that we may previously have thought to be out of the bounds of our digital lives. In this respect, the drone represents the network becoming a living entity, transcending its otherwise immobile structures, tied to large data servers that are reliant on cables and satellites.

In part, this is what makes the drone such a phenomenal technology, as it allows a radical detachment of the technology from a physical infrastructure. Drones are not simply valued neutral platforms, capable of remarkable feats of creative endeavour or destructive acts. Instead, they compel humanity to hold a mirror up to itself and ask questions about what kind of future we may wish to create.

In 1987, one of the most well-known drone visions is found hidden in Robert Zemeckis’ Back to the Future II when Marty McFly visits the year 2015, we see a fleeting glance of a drone taking a dog for a walk. Fast forward to the actual 2015, and we see this possibility floated as a comedic idea in a drone product promotion [11] And 5 years later, during the Coronavirus lockdown, we see an actual dog being taken for a walk by a drone [12].

Interrogating the desirability of such circumstances has often been the purview of drone artists, which is why it’s so crucial that artists gain early access to new technology. Without their involvement, we’re left picking up the pieces of a world which pursues technology in the hope that everything will be made better by our simple employment. More often than not, it creates simply a new set of problems for us to figure out.