Text by Ryan Madson

![The new single from Telefontornet_by_St. Claire [Miroslava + Ryan]_2021](https://www.clotmag.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/The-new-single-from-Telefontornet_by_St.-Claire-Miroslava-Ryan_2021.jpg)

The technological singularity contains nightmares. Not the ones depicted in sci-fi movies or video games that feature human survivors at war with omnicidal superintelligent robots, but vivid nightmares of intensification and mutation of today’s dystopian worlds. The lived realities of socio-economic inequality, racism, sexism, social abandonment, colonialism, xenophobia, and other forms of oppression will be amplified by the singularity. In other words, dystopia for the rich, techno-apocalypse for the poor!

Technology always reflects the society that creates it [1]. Biases and power structures of the dominant culture are embedded within and extended through our technologies, often in ways that are invisible. Without adequate safeguards and radical restructuring in how we imagine, produce, and use technology, a hypothetical singularity will emerge from the consumer technologies and market logics of technocapitalism or from the invasive technologies of authoritarian surveillance states.

What sort of malign surveillance apparatus, for example, would a superintelligence, programmed with inherent biases against minorities and poor people, inflict upon its host society? What will be the fate of human labour and the working classes when full automation takes over? What does personhood mean for transhuman entities when our models for what constitutes a person are inherently privileged? Following an extreme thought experiment, who will benefit from the singularity? Who will be the losers?

Any ontological reckoning with technology that attempts to describe the present moment must account for platform capitalism and Silicon Valley’s fictions of frictionless tech “ecosystems” that seek total market domination: Technology at the service of Global Capital. So-called disruptive technologies continue to find new ways to exploit our personal relationships, interests, and consumption habits to grow the attention economy. Instead of fulfilling a liberating, ludic vision of utopian cyberspace, our future digital interiors will consist mostly of mundane user-driven content, transactional media, addictive entertainments, and endless rabbit holes of misinformation that fuel cultural enmity.

Future breakthroughs in computing, including a singularity, will crystallise these tendencies. Our algorithmic overlords will become further emboldened to prioritise profit and market share above all else. Under state control, advanced technologies and surveillance regimes will coalesce as hyper-totalitarianism. Technology drives the inequities and inequalities of tomorrow.

These are unsettling prospects. They should prompt us to rethink the political and moral dimensions of our popular technologies and question the motives behind emergent digital tools. Uncritical embrace of any new technology reveals tacit approval of market systems and technocracies that reinforce unequal conditions. Embrace of the singularity concept means relinquishing everything to these oppressive systems.

Briefly defined, the technological singularity is a hypothetical future event wherein humans are overtaken by superintelligent machines and/or digitally-enhanced transhuman intelligence. The concept is analogous to a mathematical singularity, where an output variable increases towards infinity within finite time. The singularity at the centre of a black hole is the apocalypse of Newtonian physics.

This essay proposes an alternative singularity that subverts the notion of a singular, universal event. An alternative that we might call the lo-fi xngularity represents an unknown future condition, one that we might anticipate with hope rather than dread. Xngularity anticipates the emergence of superintelligent machines derived from open source platforms, empathetic AI, and a free internet. Future technologies might therefore enable more inclusive and expansive digital tools and networks: distributed technological mobilities, a plurality of information commons, and people-oriented, rather than profit-driven, platforms that promote digital emancipation [2].

The modifier lo-fi (lo-fidelity) derives from sound recordings of minimal production and raw quality. Sonic characteristics include noise, glitch, delay, and distortion. In electronics, lo-fi also refers to the correspondence of output signal to input signal. Lo-fi is prone to error and loss (of information, of clarity) but open to interpretation and comfortable with imperfection. The lo-fi attributes of xngularity act as a brake to the omnipotence of a hypothetical intelligence explosion.

The emergence of an artificial superintelligence (ASI) must become future-proofed and reconciled with attributes that preclude a hostile takeover. First, ASI must learn to be dependent upon human agency for mediation, oversight, and companionship. Second, an open-source ethos — informed by selflessness, pluralism, improvisation, and non-hierarchical design — must shape the syntax and operating systems of ASI. Humans and machines might then co-create at the highest levels of imagination and invention.

The alternate xngularity (or xngularities, as we shall see) has the capacity to decolonise technology and empower humans in the next phases of our social and political development. A lo-fi xngularity might have characteristics of cybernetic countercultures, such as the Chilean Cybersyn project or the communalist aspirations of Whole Earth Catalog and WELL (before corporate consulting took over). Xngularity is defined by bottom-up networks, open access, and free and open-source software (FLOSS), in combination with the awesome but as-yet-unrealised potentials of ASI. It also borrows from recent philosophical and critical programs of cosmotechnics, technofeminism, and other alternative digital cultures, discussed further below.

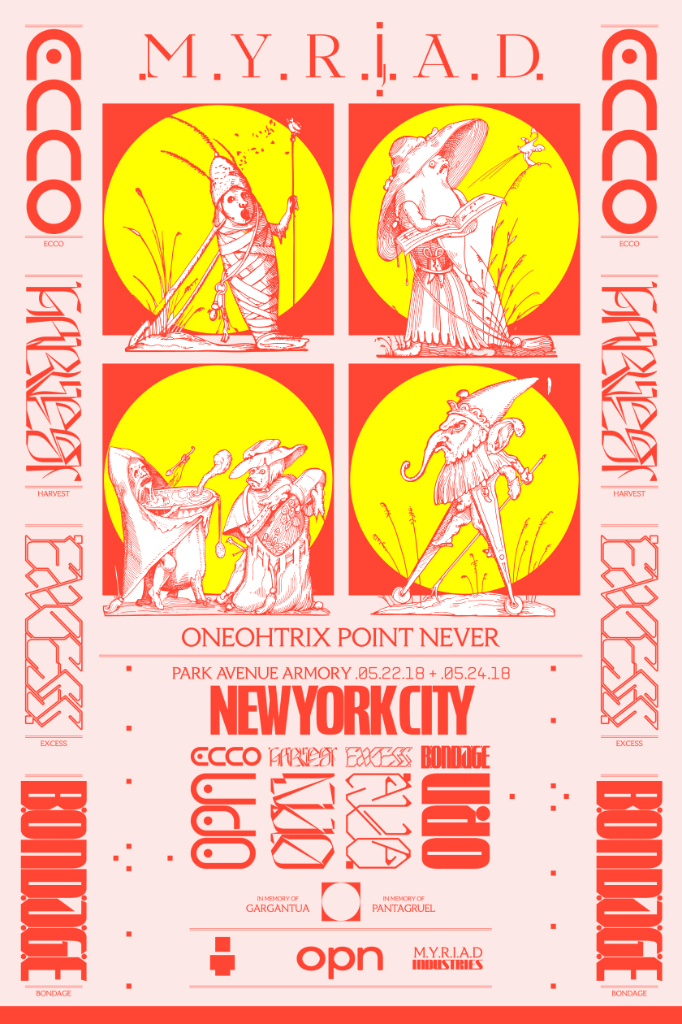

Right: MYRIAD Armory Poster, Oneohtrix Point Never (2018)

The Singularity Myth

The unfolding of an actual singularity would probably be impossible to comprehend due to its magnitude and complexity. Like a hyperobject, mysterious and massively distributed, it would lie beyond the threshold of awareness for many people [3]. Climate change, for instance, is a hyperobject that touches upon nearly everything via knock-on effects that are often unpredictable. Or the singularity might be viewed through a glass darkly ― an enigmatic, bewildering series of technological transformations which overshadow human progress.

Futurist Ray Kurzweil has been perhaps the most influential prophet of the singularity. His book, The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology, continues a lineage of pop futurism inaugurated by Future Shock, the 1970 classic of speculative nonfiction by Alvin Toffler and Heidi Toffler [4] [5]. Books in the pop futurist genre have in common a prophetic narrative spin on technological trends which inspire titillating visions for the near future. Futurism as a commodity.

They tap the ancient power of the future to fascinate and frighten, in a way that both soothes and feeds our contemporary anxieties, notes Samantha Culp [6]. [Pop-futurism] presupposes an audience who want to disrupt industries while preserving the status quo. Even futurists like Kurzweil present concepts that seem revolutionary—the singularity, the possibility of immortality—in language that is bounded by individualist, entrepreneurial thinking. Threaded through it all is the logic of optimising everything, even our souls [7].

Yet these fever dreams of the pending intelligence explosion appear unable to imagine a future beyond the strictures of late capitalism. Technology remains tethered to dominant ideologies of the present. From a political perspective, futurists like Kurzweil fail to say anything meaningful about technological futurity. For the whole point of Kurzweil’s speculation, writes cultural critic Steven Shaviro, is precisely to bring us to utopia without incurring the inconvenience of having to question our current social and economic arrangements [8].

Technology researchers have consistently pointed out how class, race, gender, sexuality, language, and geography are essentialised and operate as structural biases across digital platforms [9]. The work of essentialising and ordering on the basis of biology or culture writes technologist Kate Crawford, has long been used to justify forms of violence and oppression [10].

How would a singularity that is driven by ASI avoid the pitfalls of essentialisation and normative cultural biases? Xngularity, as we speculate here, seeks to abolish such biases and normalise all possible identities. It explores the notion of “user groups” in the discovery of a technological era that is emancipatory and radically inclusionary.

Technodiversity surrounds us

The singularity has a history prior to tech gurus and sci-fi writers giving it a name. Nicolas de Condorcet, an 18th-century mathematician, described an intelligence explosion brought about by advancements in industrial machines. Hegel wrote about the teleological nature of history and how the human spirit will follow an ascending arc to self-realisation and the ideal of absolute knowledge — a sort of non-machinic, epistemic singularity. Hegel’s telos prefigures the singularity myth, also built upon a human tendency to see continuous progress in historical events, which is used as evidence to forecast the future.

In the 1930s, the Jesuit priest and geologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin proposed the noosphere. From the process of “cosmogenesis,” or the evolution of complexity and consciousness in the world, a layer of unified human thought and activity will emerge and transform the planet. The noosphere leads to transcendent self-awareness or the singularity as rapture [11].

At the dawn of the digital computing era, Alan Turing asked if machines could think and concluded that artificial intelligence would eventually eclipse human intelligence: it seems probable that once the machine thinking method had started, it would not take long to outstrip our feeble powers [12].

His famous measure for determining the efficacy of artificial general intelligence, known as the Turing test, or imitation game, itself inspired by a parlour game of guessing someone’s gender or occupation based on notes exchanged between players on the other side of a partition, evaluates a machine’s ability to exhibit human intelligence by communicating with a person using natural language. The indistinguishability of human intelligence from artificial intelligence is a precondition for the singularity. Irving John Good, a colleague of Turing, later originated the intelligence explosion concept that precedes machine superintelligence [14].

The history of the singularity derives from a procession of white, western-educated male theorists and technologists, an obvious blinkering of perspective. While this fact should not invalidate the singularity concept, there is a need to question its embedded assumptions. A point-by-point historical-critical analysis is beyond the scope of this essay. One central assumption must be critically evaluated, however: the flawed structure of technological universality that undergirds the mechanics of various singularity narratives.

Anita Say Chan has called this the “myth of digital universalism.” Her book Networking Peripheries deconstructs the notion of technology as a top-down ideology that flows from Silicon Valley and the various “silicon alleys” of the developed world to the so-called peripheries and the global south [14].

Chan explores technological cultures in South America and finds evidence of regional innovation, for example, the FLOSS initiatives that provide national platforms while circumventing Microsoft’s market dominance. Chan calls out the hubris in assuming that digital culture is monolithic, deriving only from supposed centres of technology, while the rest of the world passively consumes their products.

“Technology transfer,” the process of seeding tech products from centres of R&D to the provinces, too often results in ongoing dependence on proprietary technologies rather than adaptation, modification, and indigenous innovation. As Chan and other technology researchers demonstrate, the stereotype of hackers and pirates at the margins, who supposedly copy and steal intellectual property from tech giants, belies the innovation that is actually occurring. This false narrative is partly the result of marketing ― the perception that an elite handful of tech firms maintain a global monopoly because of superior innovation.

Right: They Learned to be Musical, Ryan Madson

Uncritical acceptance of this top-down model of innovation and progress derives from a Eurowestern-hegemonic worldview of Enlightenment reason, which has today culminated, or convulsed, with the global triumph of neoliberal capitalism. Similar to critiques of humanism, which conflate the ideal human subject with modern European man, many technologists view the ideal “user” as a cosmopolitan middle-class consumer. The moral objectivism of tech firms precludes the views and values of marginalised, minoritised, and “othered” populations.

Technologists who support the flourishing of regional innovations must seek means to decolonise technology and create alternative narratives where tech is driven by human agency. Countermeasures include myriad local realities, adaptive practices, and distinctive digital cultures. Innovation truly exists across the globe. It is worth noting that many of today’s tech centres were once peripheral. In the beginning, the hinterlands of Silicon Valley were just office parks with cheap rents.

New centres have arisen in the last twenty years. Places like Bangalore, Jakarta, Lagos, and São Paulo, and regional innovation hubs like Chennai, Penang, and Zhongguancun challenge the western paradigm and subvert the dominance of Asian tech capitals. As networks of privilege are better understood, peripheries that can resist and adapt are poised to replace the official centres of power.

The antithesis of top-down, Silicon Valley enlightenment is technodiversity or the dispersal of innovation and the existence of grassroots digital cultures. Philosopher Yuk Hui observes that technology is not anthropologically universal. [I]t is enabled and constrained by particular cosmologies, which go beyond mere functionality or utility. There cannot be a single technological paradigm, but rather multiple ‘cosmotechnics’ [15].

Hui argues that there has never been a universal concept of technology and its representations. Instead, multiple and divergent cosmotechnics are intrinsically linked to local, vernacular worldviews. Because worldviews vary across and within cultures, any universal definition of technology can only be a colonising proposition. Although superficial similarities persist across cultures, the actual impacts of technology are relative to context. Eurowestern countries and Asian regions may consequently evolve into radically divergent digital futures [16].

Scientific and technical thinking, writes Hui, emerge under cosmological conditions that are expressed in relations between humans and their milieus, which are never static [17]. All nations and societies have been colonised by technology, but not necessarily by the same ones or in the same ways. Some have been exploited or provincialised to a greater degree than others. The cosmotechnics of non-western societies demonstrate how pluralism can challenge narratives of modernity. Different societies have access to unique conceptual and technical tools, in theory deploying them to reconcile oppositions between technics and nature, between digital realms and lived experiences.

Instead of negating technology and tradition, writes Hui, such a program will have to open itself to a pluralism of cosmotechnics and a diversity of rhythms by transforming what is already there. The only way to do this is to unmake and remake the categories that we have widely accepted as technics and technology.

Hui’s marvellous writings on technology, especially The Question Concerning Technology in China, dive deep into comparative technics and related concepts ― time, mathematics, geometry ― of both Eastern and Eurowestern philosophical traditions. His goal is to renew culture(s) through regionally-distinctive technological worldviews, each with robust links to tradition and homegrown digital cultures.

The obstacles to this are synchronisation and homogeneity. The worldwide web and ubiquitous mobile technologies have effectively colonised the planet, making us beholden to the same services, brands, gadgets, and trends. Hui observes that people everywhere are conditioned by the same digital rhythms. News cycles, popular YouTube channels, video editing trends on Tik-Tok, daily posts of puzzle scores for Wordle and Candy Crush, and many other popular distractions have become habituated to our biological rhythms and social routines [18]. The solution? To allow technology and local traditions to co-evolve while resisting the colonising tendencies of corporate and statist technologies.

Eurowestern stereotypes of Chinese tech have tended to emphasise the big brother surveillance state and national industries built on intellectual property stolen from the west. The reality, or innumerable parallel realities, encompasses a spectrum of technological innovation and adaptation. Chinese surveillance and social ranking of citizens according to relationships, shopping habits, travel, and opaque bureaucratic criteria are scary, but so too are the workaday intrusions of corporate surveillance which westerners appear to take in stride.

The Chinese government keeps data on all Chinese citizens and uses it to oppress minority groups such as the Uighurs. However, the state also sponsors tech innovations for pastoralists, farmers, and other groups in the provinces. Such investments are unheard of in most parts of Europe or North America. Technology in China is pervasive, a force for both good and evil, progress and oppression.

An important conceptual precursor to xngularity derives from Chinese popular culture: Shanzhai (山寨), literally translated from Mandarin as “mountain fortress,” refers pejoratively to imitation consumer goods such as smartphones or luxury clothing which are marketed at lower costs than the genuine article. Shanzhai are often perceived as inferior in quality, yet some products possess a certain kitsch value which excuses any technical flaws. The concept has further evolved with more positive connotations. Technologists such as Xiaowei Wang have elevated the shanzhai concept through associations with creative hacking, technical ingenuity, and innovative risk-taking in China. The resulting products are often superior to the ”originals,” flipping the script on innovation.

In the case of mobile phones, the quintessential shanzhai product, technologies become superior due to the adaption of locally useful features such as a camera app that can identify counterfeit yuan or a mode that prevents tracking VPN use. Many shanzhai feature open-source operating systems or open access hardware specs. Smartphones are known for ease of repair and the ability to modify and upgrade inexpensively. Wang, in her book Blockchain Chicken Farm, explains how designers and engineers of new shanzhai products build on each other’s work, co-opting, repurposing, and remixing in a decentralised way [19].

Wang describes the Huaqiangbei electronics market in Shanghai, where a shopper can find every conceivable technological product for sale — holograph generators, 3D printers, modular cell phones, and at least one proprietor who plans to open a cyborg stall to sell augmented body parts. Firms compete for customers, yet they also collaborate to improve their wares.

The new emerges from surprising variations and combinations,” writes Byung-Chul Han. ”Shanzhai illustrate a particular type of creativity. Gradually its products depart from the original until they mutate into originals themselves [20]. Despite dominant economic models, shanzhai thrive on decentralised technology and fluid relationships with users. Copies proliferate only to become transformed into something new. They are seldom produced using proprietary hardware and software, which consumer technologies in the west rely upon to maximise profit from planned obsolescence and costly upgrades/repairs. Shanzhai decolonise technology using methods that are counterintuitive to technocapitalism. They demonstrate how local digital cultures can adapt and thrive by breaking with technological universalism.

Silicon Valley has the clocks, but the periphery has the time. Out in the peripheries, technologists and communities of users are shaping their own cosmotechnical worldviews and sense of futurity. Local advantages include endurance and persistence — the time needed to (re)invent, iterate, and repurpose technologies, as shanzhai have shown.

Ties to culture, community, people, and place are stronger than any imported technology. For now. Yet technology continues to colonise the planet, touching on everything. We are only dimly aware of the frightening extents to which our private imaginations and public aspirations are being shaped by devices and digital media. If societies can sustain a semblance of tradition and local attachments, then tools will remain available to challenge and resist universal rhythmicity. Technodiversity will create paths to more optimistic futures, to xngularities that will multiply human progress. At this critical juncture, our technologies might destroy us. Or they might empower us to anticipate and build the futures that we wish to inhabit.