Text by Stefano Corbo

In 1638, seven years after Mount Vesuvius erupted, the Jesuit scholar Athanasius Kircher traveled to Naples and climbed the volcano that had just caused the death of more than 4,000 people. After descending into the crater to measure the temperature, Kircher reported:

I thought I beheld the habitation of Hell, wherein nothing seemed to be much wanting besides the horrid fantasms and apparitions of Devils. . . . I heard horrible bellowings and roarings, and there was an unexpressible stink.

. . . The smoke and fire and stench continually belch’d forth out of eleven several places, and made me in like manner belch, and as it were, vomit back again, at it [1].

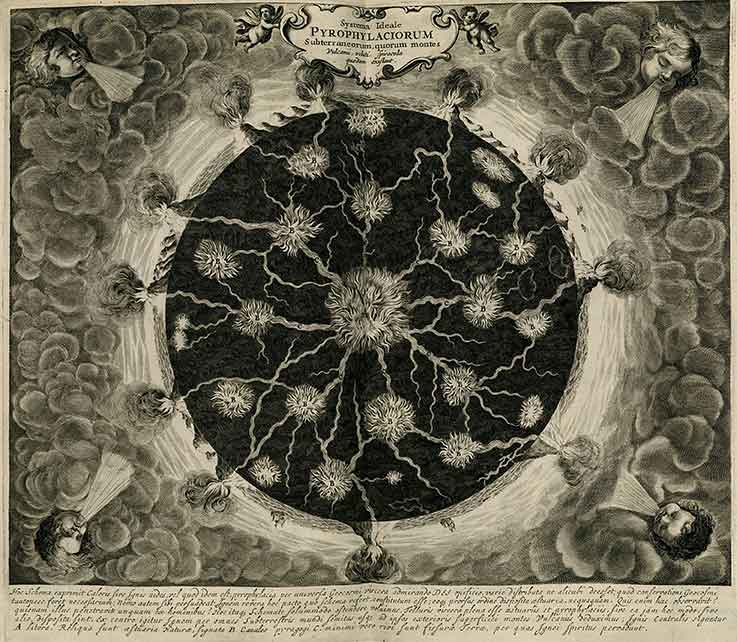

His encounter with the brutal and tumultuous Mount Vesuvius piqued his curiosity and inspired his further explorations of Earth’s interior. This culminated in the famous Mundus subterraneus, a comprehensive, twelve-volume atlas published between 1665 and 1678. Mundus subterraneus expresses Kircher’s belief in an interconnected subterranean world with a mysterious system of arteries that reaches the center of the globe—a mass of flame sending heat to the surface through channels and fissures. Fascinating maps support this hypothesis: mountains, oceans, and volcanos are described as visible manifestations of this incessant magmatic flow (fig.1).

Despite some of his unscientific theories, Kircher is credited with providing an exhaustive description of the world where water, fire, sun, moon, fossils, and even lost islands obey the same general logic. At the same time, Mundus subterraneus was an attempt to satisfy the curiosity of a large, erudite audience. Over the centuries, the idea of an underground world populated by invisible forces has fueled the fantasy of artists, scholars, and scientists.

From the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, to Plato’s Allegory of the Cave, to Dante’s exploration of Hell, mythology, literature, and the underground have often overlain and morphed into unique narratives. At the root of this fascination are two things: on the one hand, the subterranean is associated with fear and danger—the domain of evil. On the other hand, it is also seen as an oasis for freedom and imagination. As Kircher showed, the subterranean symbolized thirst for knowledge, fear of the unknown, and the will to push the boundaries of human intelligence.

In the realm of architecture and design, humans have explored the space below their feet for different purposes: to flee persecution and war, to find protection from severe weather, and to improve city life. By carving, digging, hiding, and unveiling, many different kinds of structures have been built over time: bunkers, catacombs, aqueducts, and, more recently, dwellings, data centres, and seed banks.

This book aims to cover the history of such spaces under a general definition: the Underworld. My premise is that the Underworld is a broad interpretative category that includes but is not limited to subterranean examples. It reaches beyond its most immediate and literal interpretation. It includes architecture whose internal functioning is not completely revealed or whose spatial articulation is based on a relationship between visible and invisible elements.

Furthermore, underground spaces belong to the Underworld, but the Underworld is not always belowground: it can be inaccessible or far from prying eyes, yet located in the urban core. The Underworld manifests itself not as a specific physical condition but in the role it plays in a particular context. Despite their qualities, these spaces have an indirect but relevant impact on the built environment. In other words, the Underworld is an invisible extension of historical and contemporary architectural production.

The fascination with the deep unknown, as described in the literature, sometimes distracts us from the essence of these secret spaces: that they are formed by the same economic and cultural forces as visible architecture. Global phenomena such as migrations, epidemics, and wars have always had a clear correlation to the Underworld. Because of their unstable nature, underworld spaces are constantly evolving, and we will explore their evolution in relation to the outside world in more than eighty projects from different eras and in different geographic locations. The following five chapters offer lenses through which to understand the Underworld’s physical and symbolic relevance.

Upside Down: The Making of the City

Since the first urban settlements, the Underworld has been an inexhaustible source of exploitation. Mining, for example, is one of the most extreme examples of the Underworld: to extract fossil fuels, metals, and minerals, the underground has been continually eroded by tunnels and work areas. This required a huge technological effort, and the outcome was a unique microcosm physically separated from the aboveground world but also deeply tied to its economy.

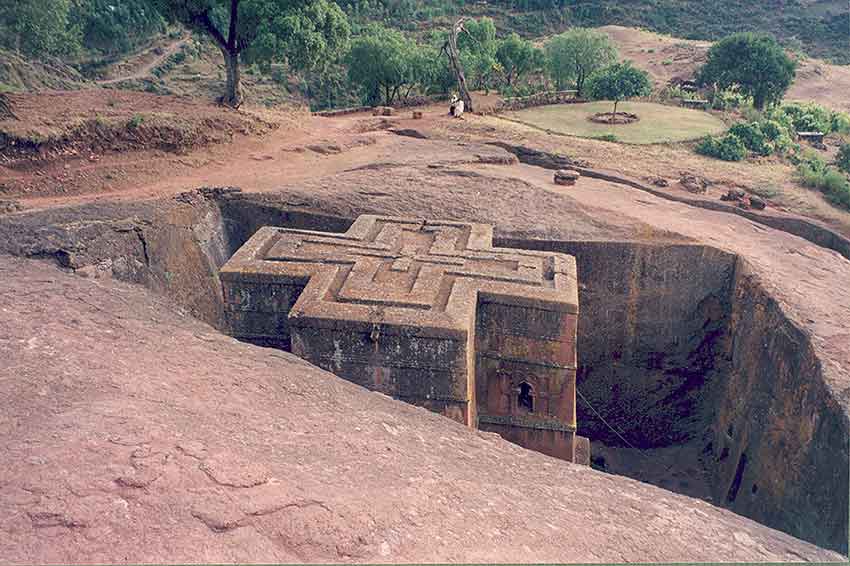

In addition to mines, a parallel universe composed of aqueducts, cemeteries, and sewers runs beneath the city surface and has guaranteed its functioning over the centuries (Fig.2). The exploitation of the Underworld for economic and engineering purposes continues today in new architectural forms. The need for secure storage for computer systems, internet servers, and IT operations has produced the rise of new, mysterious structures— so-called data centres. This chapter will explore old and new infrastructures by deconstructing the city to reveal its inaccessible spaces (Fig.3).

Design as Warfare

An intriguing perspective on the Underworld comes from the military complex. If, during World War II, anti-raid shelters represented a rudimentary yet successful solution to protecting citizens from massive bombing operations, in recent times, the fear of nuclear attacks has led many countries to rethink their defence systems. Fallout bunkers and tunnels were built around the world, and complex underground cities could accommodate thousands of people in wartime.

While some of these projects were designed to double as military structures and as public facilities in peacetime, today, most of these spaces have been abandoned and closed off to the public, their destiny uncertain. However, there are some exceptions. This chapter will present examples of bunkers turned into tourist attractions—monuments to the Cold War—and tunnels converted into museums and art galleries. In other cases, these historic structures have been preserved and incorporated into national parks and reserves (Fig.4).

Life and Death in the Underworld

Subterranean settlements can be found everywhere, from Cappadocia, Turkey; to Matera, Italy; to China with its sunken courtyards; many are examples of vernacular dwellings. Nature is carved out to achieve favourable living conditions, especially in response to extreme weather. All these examples prove the existence of an anonymous and collective intelligence—in contrast to the individual act of the artist-genius—capable of producing remarkable architecture despite scarce resources.

Historically, the Underworld also symbolized the bridge between life and death. Over the centuries, sacred spaces and catacombs have been built underground, providing shelter for those escaping religious persecution (Fig.5). Today, we face a renewed interest in subterranean ways of living. On the one hand, the economic elite has begun to install swimming pools, billiard rooms, car parks, and even tennis courts in the basements of their elegant houses.

In London, for example, between 2008 and 2012, permission was granted for more than 800 subterranean excavations in the Kensington and Chelsea neighbourhoods [2]. On the other hand, growing environmental concerns are prompting architects to root their projects in nature—an attempt to live in harmony with the earth.

Emerging from Darkness

As urban developers continue erecting new buildings, an opposite phenomenon occurs: abandoned structures once belonging to an invisible urban network are being turned into public facilities and finally given back to the community. Reemerging from an unseen past, these buildings are officially being absorbed into the urban fabric. This process of adaptive reuse offers a wide range of examples: caves converted into post offices, industrial silos into houses or art centres, and medieval churches into bookstores. In this way, design becomes a progressive process of unveiling.

On Nature and Artifice

The Underworld is not only the expression of a hidden universe. It can also be a hybrid of components: nature and culture, architecture and city, and so forth. For example, nature does not just mean the presence of greenery. Nature can be artificial—in other words. It’s possible to reproduce nature in vitro. From the construction of monastic structures carved out of the mountain to biophilic design experiments to buildings that seem to merge with the landscape, nature is represented and incorporated into complex environments (Fig.6).

By dissecting the Underworld in these five spheres, this book aims to prove that despite their differences, both exterior architectural expression and its invisible counterpart are produced by the same agents and dynamics. In other words, the exterior built environment is but a visible expression of a broader scenario in which visible and invisible elements are intertwined. Once we make this connection, a counterhistory of architecture can finally be written.