Text by Daryl Worthington

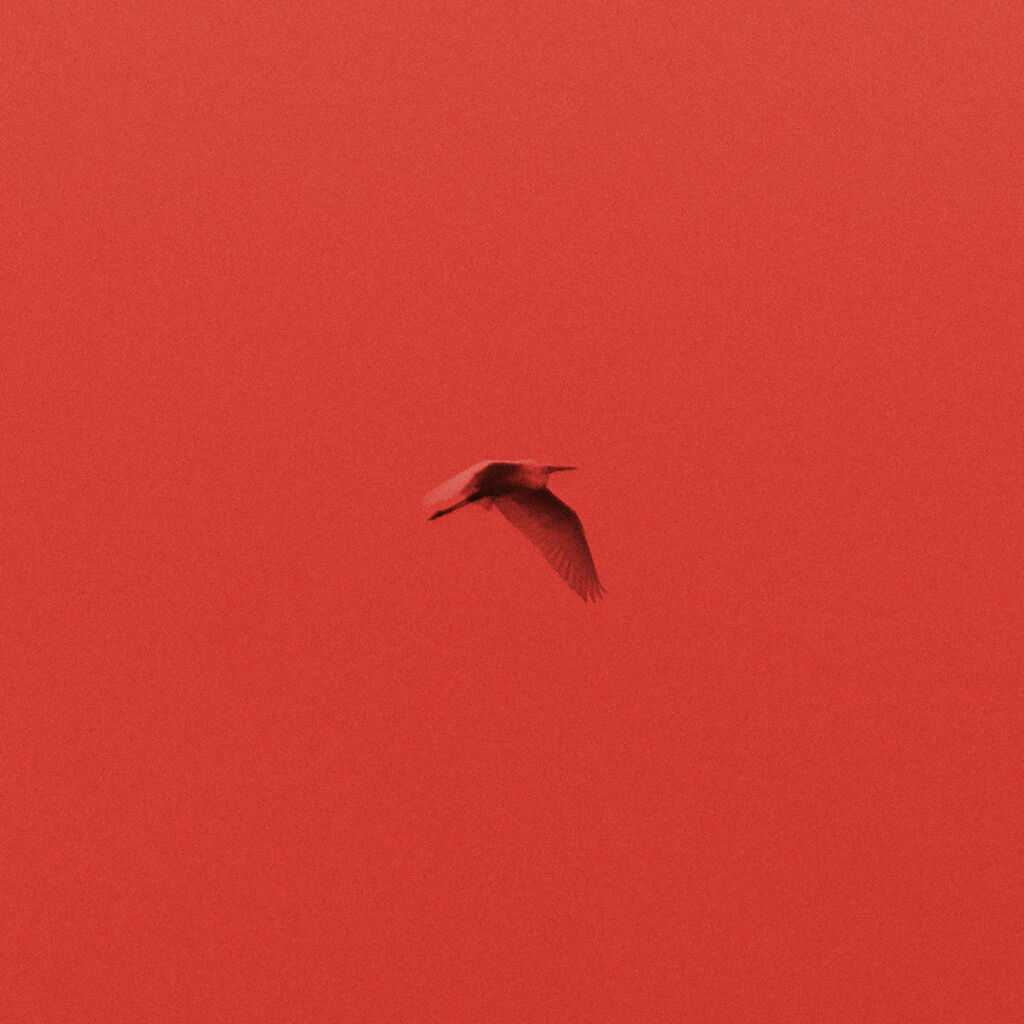

A bird sings like a synthesizer on ‘mana’, the opening track on Rosso Polare’s new album, Bocca D’ombra. The avian call emerges through rustling field recordings, nestled among other wildlife chirps and squawks. As clarity grows, it takes on a rhythmic pattern that seems sequenced. Though relatively brief, it provides a base for what follows: vocals, acoustic guitar, and more organic sounds sprouting from the framework that’s been set. The bird call is an aural misdirection, a transmogrification between organic and synthetic which reappears throughout the whole album. Such disorientating gestures are common in Rosso Polare’s music. Since their debut, 2020’s Lettere Animali, their practice has adopted a distinctly blurry position on the boundary between human and non-human-made sounds.

When I speak to the duo, Anna Vezzosi and Cesare Lopopolo over email and video call, they’re preparing for launch shows for Bocca D’ombra, which is out now on Sagome. Their third album, it’s rooted in long-form, collage-like songs where electro-acoustic textures weave through flickers of traditional music and multi-species vocalisations.

The evolution of a bird call into a rhythm, it’s a message, to say, there’s really no difference, Lopopolo explains. It’s a way of seeing sounds just as sounds. And not as bird sounds, human sounds, instrument sounds. Rosso Polare highlight anti-speciesism as a thread running through their music. Put simply, a strive to avoid valuing human sound sources differently to non-human ones. Lopopolo gives the example of cacophony, a term which, when applied to surroundings, especially environmental, suggests a typically pejorative relation to the harmonic or musical. Such reductive distinctions are something which the duo strive to evade.

We tend, as a species, to look at what is not produced by us as unorganized sound, suggests Lopopolo. It passes by as white noise for many people. The thing we started with Lettere Animali was trying to equalise the differences between organised and unorganised sound, between what is produced by humans and what is not produced by humans.

This sense of equalisation is especially pronounced on Bocca D’ombra. The presence of electronic drones and pulses is more explicit among the melodic and the acoustic than previously. Yet there is never a sense that one sound is a background to another. Their music is simultaneously homogenous and heterogeneous. It acts like a graphic equaliser tweaked to bring a whole soundscape into equal fidelity without losing the nuance of the discrete elements contained within.

This is reinforced by the fact it’s not just equalisation across the organic/synthetic divide that Rosso Polare explore on Bocca D’ombra. They also do it within the realm of human music, engaging with the vernacular and the ornate on equal terms to create a unique pastoralism. Bell rings appear frequently throughout the album, while the second track, ‘albanella’, includes a rendition of a Renaissance chacone, an elegant form traditionally played on guitar and lute. In contrast, on ‘golagialla’ horns “imprecise and with approximate intonation” from folkier medieval traditions emerge, while the album’s title track opens with a startling swarm of horns and pipes taking inspiration from Tibetan rituals.

It points to an area the duo hope to explore in greater depth on future projects, specifically, the diverse, local traditions embedded in Italy’s regional soundscape. We’re not surrounded by these vernacular styles anymore – we need to go and find it. Vernacular music is always considered the lesser side of music. We want to bring it back, but manipulated in a way, Lopopolo explains.

While the use of nature recordings and references to traditional sounds are currently pervasive in experimental music, Rosso Polare’s practice remains conceptually and aesthetically unique. Their recordings do not try to accurately capture a place, and neither do they simply use field recordings as furnishings or texture. The array of sounds they use feels intrinsic to the oddly transitory worlds their interactions, with each other and their environment, build. This comes across especially clearly when seeing Rosso Polare perform live.

Their palette includes kalimba, guitar and various wind instruments alongside effects and electronics, yet one of the most striking actions in their performances is Vezzosi scraping a contact mic across the venue’s floor. The gesture acts as a bridge, reinforcing that the sounds they are using are not immutable but situated, existing in a state of flux and strange permeation. I suggest that what they do is closer to synthesizing – combining components into a new whole – rather than capturing.

We don’t want to record a certain area or study a precise environment, as we are not operating from a ‘scientific’ side and certainly don’t want to, they explain over email. Field recording for us is more of a vessel to convey a narrative, and could be very akin to what movies do in absence of dialogue.

They continue: It is fascinating to observe how a natural sound can be transformed by human and artificial connotations, and vice versa. It is impossible to escape the influence that our interventions have on the field recordings, rather we want to ‘notice’, indicate and be noticed, as if all sounds – human and natural – were intermediate translations between one language and another.

This way of incorporating sound is not simply theoretical, it reflects Vezzosi’s background in a rural part of Lombardy. I grew up with a specific relationship with nature and animals, she explains. They were like friends. I lived in a small town, there weren’t many people to talk to, I was very shy, and I was used to walking in the field with my thoughts, or looking for new insects or birds. I grew up in this environment – it’s my way of discerning reality.

Although Rosso Polare stress that their work is rooted in instinctual explorations and improvisations, two key theoretical frameworks influence their approach. The first is biophony. Coined by sound ecologist Bernie Krause, biophony is part of a trio of layers to distinguish a soundscape. The biophonic encompasses the sounds made by living organisms within a particular biome, while geophony covers non-biological natural sounds like wind and flowing water. Anthropophony refers to the sounds humans make. Lopopolo explains that as well as having a specific interest in the biophonic layer in their music, they also see it as a way of thinking about sounds outside of hierarchies such as musical and non-musical.

Cani Lenti, Rosso Polare (2022)

Lettere Animali, Rosso Polare (2020)

Rosso Polare also describe Timothy Morton’s concept of ecognosis, elaborated in his book Dark Ecology, as a reference point for Bocca D’ombra. As Morton writes in Dark Ecology: It [ecognosis] is like becoming accustomed to something strange, yet it is also becoming accustomed to strangeness that doesn’t become less strange through acclimation. Ecognosis is like a knowing that knows itself. Knowing in a loop; a weird knowing. Weird from the Old Norse, urth, meaning twisted, in a loop.

This resonated with Rosso Polare’s existing ideas around biophony and anti-speciesism: The record itself is not obsessively centred around this theory but rather finds some really interesting common ground on some topics, they explain. One parallel with ecognosis, perhaps, is what Rosso Polare evoke relationally in their music, through the configurations they make of typically distinct strands of soundscape.

In other words, by not isolating the human from the non-human, the incidental from the composed, they hold onto a sense of unfamiliar elements interacting. These sounds occur in the same plane, yet the strangeness of hearing them interact isn’t filtered out. Again, the heterogenous congeals into something homogenous, without losing its heterogeneity. Sounds are treated equally, without losing their individuality.

Across Rosso Polare’s three albums, the potential for sounds to carry narrative is not limited to the linguistic or the musical. According to the duo, sources used on Bocca D’ombra include: Small recordings made while searching for sounds… such as a path in Assisi, sheep in the field near Anna’s parents’ house in the countryside, various synth sessions at Cesare’s house, bird boxes near the museum where Anna works. Rather than capturing isolated places or events, they explore what their sonic imprints could evoke in a different setting. On Bocca D’ombra, these sounds are woven together so meanings become apparent in their overlaps.

These sounds refer to a very precise imaginary, that of local legends and tales, or alternatively narratives that are very distant in time, somewhat idyllic or vernacular, touching on sounds and sensations that we all probably know, the duo explain. It’s what gives a sense of comfort to anyone coming back to their childhood places for instance, especially if they originate from the North and probably from Italy in general, there is a certain common vocabulary of unconscious archetypes here, they explain.

This, in conjunction with the darker moments and artifacts in the album, strive to return sensations like dreams you can only remember in fragments and explain through hints of very distant memories. In this case there’s this idea of descent, a theme which symbolically has been described throughout history as a path into darkness, although this darkness (just like Morton’s) has a sweet component and also an initiatory aim. It’s a journey from one state to another.