Text by Charlotte Kent

Questions of high and low art, aesthetics, and curation arise when talking about blockchain and art because many in the art world have not been interested in the pixel/glitch/meme look of popular early “crypto art,” represented by the recent beeple sale or the infamous CryptoKitties or CryptoPunks. James Bridle had already made the point around the digital look in his new aesthetics.

Blockchain art’s pop aesthetic seemed tied to crypto-currency, especially in its playing card multiples and terms like “collectibles.” In due course, someone will likely contextualise these works regarding Warhol, Koons, or KAWS.

Blockchain is inherently distributed, a lack of hierarchy that appeals to many tech idealists but also those looking to widen access to the art world. Dada.art allows people to draw in conversation with each other, responding to each other’s works, a different kind of social media. It is free to join and participate. They have made curatorial sets, for example, the “Creeps & Weirdos” from 2017 that became available for sale as NFTs; even though they had archived the remaining ones, the recent flurry of interest in blockchain art led dedicated buyers to find and buy them.

The Dada.art selection represents how the art world’s engagement with blockchain doesn’t reject some aspects of centralization. Curatorial choice can help guide new audiences as many are overwhelmed when visiting popular NFT sale sites where anyone can post anything they want. Galleries are getting involved now, and some platforms will likely focus exclusively on art or have channels representing curated selections. This doesn’t need to be a rejection of the distributed and decentralised ethos of blockchain as long as these centralising elements act in a decentralised manner.

Beyond the pop or Neo-surrealist aesthetics, some blockchain art will get tied to the Algorists for the way the work plays with code. As Matt Hall and John Watkinson of CryptoPunks and Autoglyphs qualify in an interview with Jason Bailey on Artnome:

We’re artists now, I guess. And especially looking at generative art from the ‘60s with fresh eyes. There were a lot of people working at Bell Labs and just experimenting and trying things out….I think we put ourselves in that camp happily, so not claiming that we’re career artists or that’s what we’re trying to promote ourselves into, but claiming the ability to express ourselves and make things just like anyone else. Autoglyphs incorporate an ASCII representation in the code on the blockchain, extending the history of artists linking the visual object with the lines of code.

With few exceptions, art isn’t actually on the blockchain. Jpgs and video files are far too large for that. When we talk about art on the blockchain, we mean someone gets a token of metadata and the art is located elsewhere. Sometimes the blockchain data will include an ASCII representation, or the physical object, as in Primavera de Filippi’s Plantoid (2015), will respond to activity on the block. Ownership can be distributed but the image typically isn’t since it exists in some location, whether as a file or on a wall. Blockchain is not a medium, per se, but an associated technology that allows artists to play with distribution and ownership practices.

Eve Sussman’s 89 seconds Atomized (2019) took an artist’ proof of her 2004 video work based on Velasquez’s Las Meninas (1656) and auctioned 2304 “atoms.” Collectors purchase individual atoms, receiving a token on Ethereum (ERC-721). Each atom contains the 9:44 minute 20×20 pixel video. Segments are available for viewing at Snark.art, a popular blockchain art site.

The owners can loan out atoms, or request a loan from the community, to produce public or private screenings. Individual atoms can also be bought and sold by collectors. The shared ownership model determines the ability to access the video. Such conceptual projects illuminate how blockchain can work.

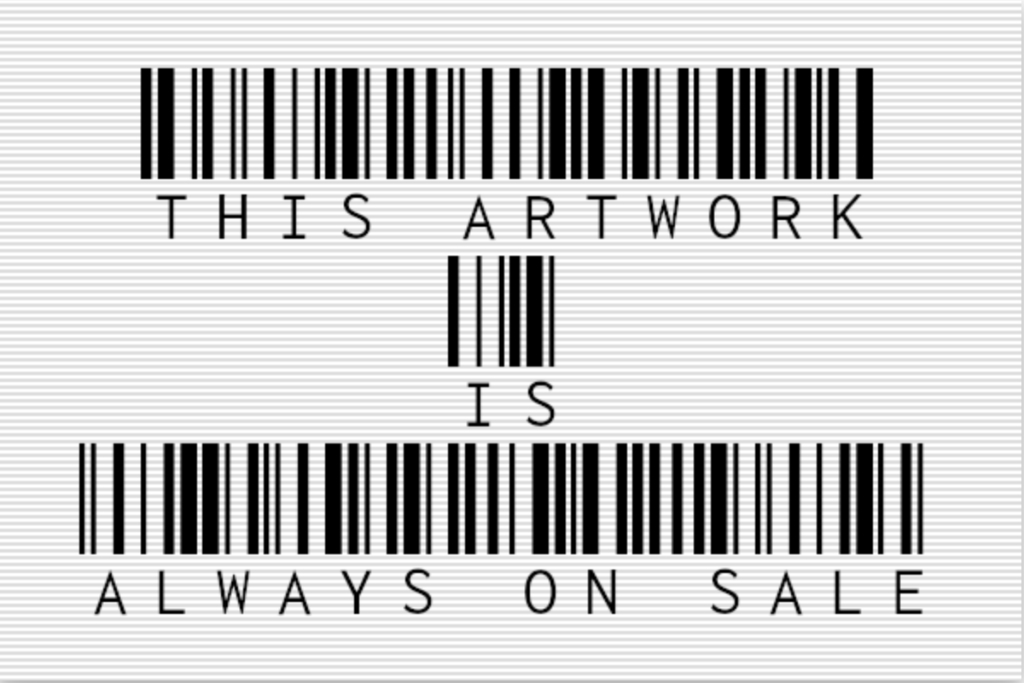

Numerous projects exist in the conceptual realm that address the technology directly. Primavera de Filippi’s Plantoid (2015), Martin Nadal’s Bitcoin Traces (2017), Simon de la Riviere’s This Artwork is Always On Sale (2019), Matt Ostachowski’s cloud works (ongoing), among others are conceptually sophisticated engagements with blockchain that were largely ignored. They dealt directly with the technology and its applications, making them challenging for those who hadn’t yet grappled with blockchain fundamentals. I expect a return to these early works and more work developed in response to the technology and its operations.

The anxieties provoked by blockchain for many in the art world reveal ongoing problems inherent to the industry. The conversation around artists’ equity, aesthetics, environment, and capital have been a part of the art dialogue for decades, and blockchain is forcing a confrontation with these issues.

The technology is new, misinformation abounds, and recent popular examples have led to ridicule or disdain. We need a more complex conversation around this technology and its potential for art, rather than the reiteration of attitudes from fifty years ago when art’s use of computers and electronics, or its relationship to government and industry, was a great travesty. (In this short series, we’ll be taking a look at blockchain art and the environment, some current group exhibits, use case models for the industry and more.