Text by Lyndsey Walsh

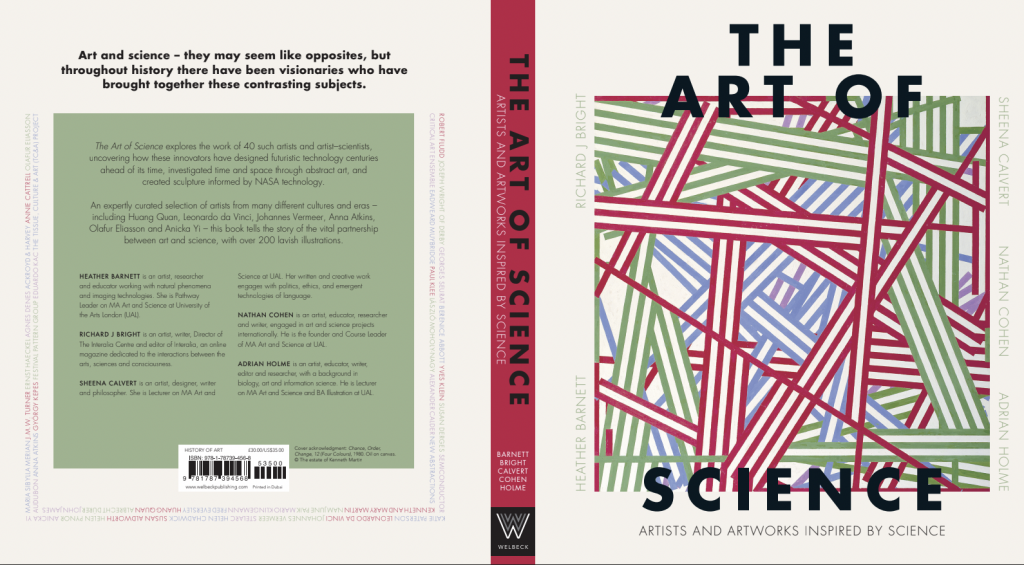

The Art of Science, a new book published by the UK-based Welbeck Publishing Group, dives headfirst into the shared threads of “human curiosity, craft and conceptualization” that transcend the disciplinary boundaries between the arts and the sciences.

The book’ ambitious narrative gives a wonderfully illustrated examination of artists and their corresponding artworks that spans 10 centuries, starting at the Song Dynasty (tenth century), moving through the European Renaissance (fifteenth century), and finally converging with the present day. The text presents itself as an introduction to the vast landscape existing between the disciplinary realms of the arts and the sciences while excited and looking forward to future ways that “science, poetics and sensual experience” will attempt to grapple with human experience and understanding our shared world.

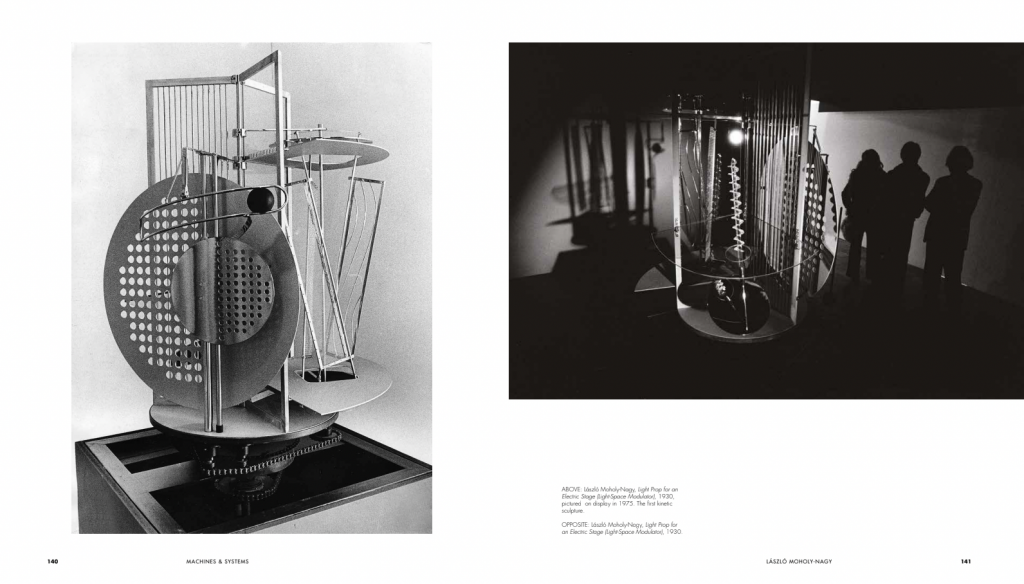

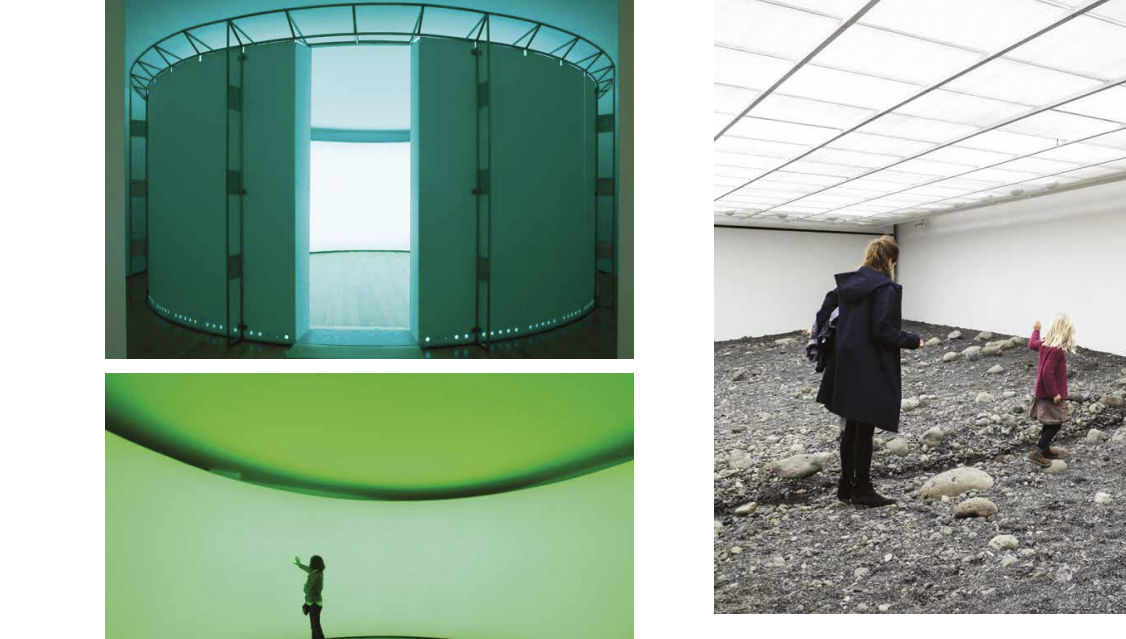

The authors examine how these threads have emerged throughout history and time to weave together a collective body of knowledge and inquiry into the human experience of the world around us. The book, authored by Heather Barnett, Richard J. Bright, Sheena Calvert, Nathan Cohen and Adrian Holme, explores the works of 40 different artists or groups of artists who are narratively related to the broad thematic focuses of Alchemy & Cosmos, Being Human, Ecology & Environment, Machine & Systems and Nature & Beyond.

These themes form a structure that allows audiences to transverse both time and space in this intriguing exploration into how artists have worked, responded, and interacted with various aspects of science and technology. Heather Barnett elaborates on the collective authorial choices in creating these thematic focuses by explaining:

We did not wish to attempt a comprehensive history that was fixed in linearity but allow motives, processes, concerns and methods to bump up against each other through history – for the reader to make their own connections. Other books exploring the convergence between art and science tend to focus on specific time periods and subjects (such as Arthur I Miller’s Picasso and Einstein) or particular biographies such as Leonardo or interrogate contemporary art and science practice (Sian Ede). We hope that the book is of interest to those who are already familiar with the field, providing interesting trajectories through history but also engaging new audiences – people who are interested in culture and science but who may not have considered the points of interaction before, of how the two fields have intersected through history.

While the realms of the arts and the sciences have come to be perceived as two divergent disciplines, this is still a relatively modern interpretation. As The Art of Science explores, throughout history, art and science have shared mutual interests in seeking to understand the world and in investigating nature and what it means to be human, as seen in the time of the European Renaissance with the rise of artist/scientists, such as Albrecht Dürer and Leonardo Da Vinci who worked fluidly across these disciplinary fields.

Heather Barnett views these binaries between the arts and sciences as existing in connection with the binary of subjective and objective forms of knowledge, explaining as if science is solely neutral and art purely expressive: one rational, the other emotional.

The subjective and objective boundary has proven to be just a line that we tend to draw in ever-shifting sand. This concept regularly pops up in the field of the History of Science and has been written on in more depth in Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison’s book Objectivity. The Art of Science exposes these shifts that have taken place over time by focusing on the individuals charging forward with their curiosity and navigating emerging technology and paradigm shifts, which has led to the redrawing of boundaries between these two seemingly “opposing” fields.

When investigating the role that context plays in facilitating this division of disciplines, Nathan Cohen observes the issues surrounding how we comprehend art and science may have much to do with cultural perspectives and the way successive generations have chosen to define what knowledge is and how it should be categorised and applied.

When reflecting on these divides in disciplinary boundaries, Sheena Calvert references Karl Poppers’ text, ‘The Myth of The Framework’, which outlines that these divisions exist as “productive spaces of disagreement” and can foster the very necessary spark to set minds ablaze in education: debate. This begs the question that maybe the modern perception of the arts and sciences actually serves a greater purpose from an epistemological perspective.

While debate can be seen as opposition, it is also a friction that spawns new ideas and concepts and energizes or motivates individuals to seek out new paths of finding and making knowledge. For Calvert, this is a point of interest as a form of collaboration since, to have a meaningful debate, individuals must meet in the middle to engage with each other—a relevant point in contemporary research. Richard Bright points out that there is a clear trend toward increasing opportunities and support for science and art collaborations in which artists and scientists take on roles that go beyond validating each other.

The artists and works selected by the authors to be featured in The Art of Science have emerged from the authors’ interests and fascinations, as they are also artists and illustrators with expertise in this field. For Adrian Holme, writing about Huang Quan presented both a great challenge and their most rewarding writing; as Holme states, it was exciting to delve into the origins in China of the striking naturalism of the bird and flower paintings more than 1,000 years ago. The Birds, Insects and Turtles scroll in the Beijing Palace Museum was a revelation to me.

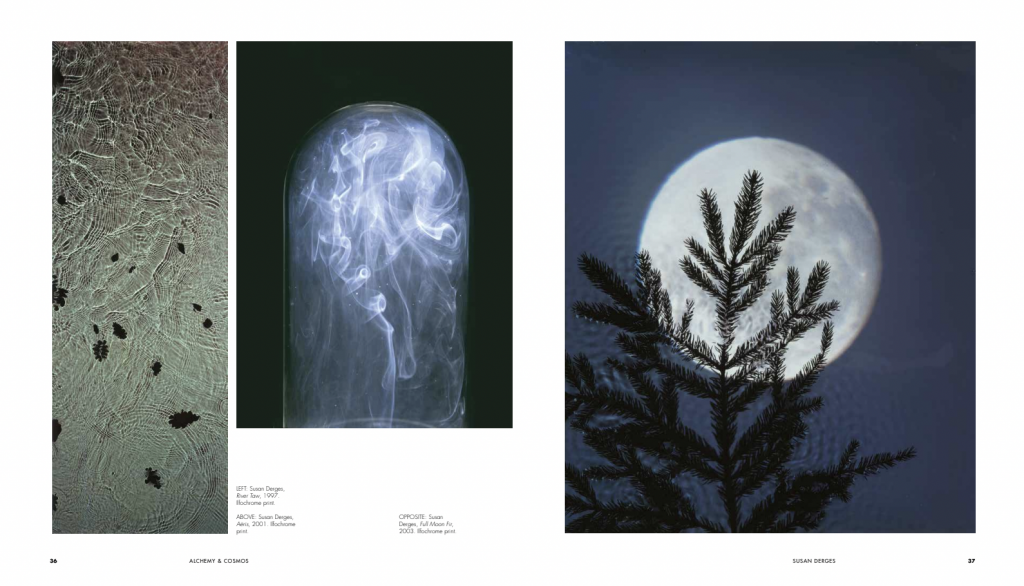

In comparison, Heather Barnett found the process of revisiting artists to dig deeper into their archives to be highly inspirational, as some of the artists featured have had great personal importance to her. Barnett cites Agnes Denes’ focus and shifts in scale, Berenice Abbott’s visual communication of phenomena existing in and around material interactions and Helen Chadwick’s explorations into growth and decay, environmentalism, the body and identity and the connections between life, matter and materials. Richard Bright also cites a number of artists featured in the book as inspiration, including the photography of Anna Atkins and Susan Derges, Mario Klingemann’s artworks working with algorithms, data and artificial neural networks and contemporary artists such as Annie Cattrell, Eduardo Kac, Helen Pynor and Susan Aldworth.

For Nathan Cohen, these sources of inspiration also have a motivational significance: When Newton spoke of standing on the shoulders of giants, his words resonated through the centuries and are as relevant today as they were then. Without the inspiration that comes from the endeavours of those whose footsteps we seek to walk in now, our vision and insight would be much impaired. As an artist, I wonder at the clarity of perception made tangible in a painting by Vermeer or the power of nature interpreted in Turner’s paintings. The list could go on and does, and I am forever grateful for this.

Maria Sybilla Merian stands out as a source of inspiration for Sheene Calvert, especially as Merian’s career went against the societal expectations and roles that women were expected to take on in the 1600s. Calvert explains, for me, Merian is emblematic of never taking as a given what information is offered. Test, explore, and find out for yourself. She also used art as a tool to present science and to question the social and lack of professional roles within science afforded to women.

When writing The Art of Science, the hardest aspect for all the authors was choosing just 40 artists to be featured for the over a thousand-year period that the book covers. There are still many artists and artworks out there to write about whose works continue to echo the lessons and stories told in The Art of Science. As such, the authors suggest that there is plenty of potential for The Art of Science to evolve into a future that can further reveal the depth and breadth of human ingenuity and creativity. Until then, The Art of Science presents a story that is both highly captivating for transdisciplinary science/art community veterans and newcomers beginning to navigate the historical and contemporary figures working in a web of complex and captivating entanglements between the disciplines of the arts and the sciences.