Text by Olya Karlovich

We feel sound with our bodies. Our auditory system, skin, brain and other internal organs all perceive sound signals from the outside world. In 1976, scientists discovered the McGurk effect [1], once again proving the interconnection between hearing and other senses (in this case, vision). Listening is a multi-layered, active and, most interestingly, ongoing process. There are no moments of absolute silence. Even while we sleep, our hearing continues to work.

The ear is a channel. It activates, wrote Maryanne Amacher, an American composer well known for her pioneering research into sound spatiality, aural architecture and ways of hearing. She was a student of Karlheinz Stockhausen and collaborated with John Cage, Merce Cunningham and many other prominent figures. Her solo and group shows took place at major art institutions such as the Whitney Museum of American Art, Casa de Serralves Portugal, Galerie Nachst St. Stephan Vienna, and DAAD Gallery Berlin. She also performed at Woodstock ‘94 and developed projects for radio and TV.

Amacher placed a listener at the centre of a piece, not a composer or artist. Combining experimental methods with scientific knowledge in psychoacoustics and an incredible intuition, she created an immersive experience at the intersection of reality and psychedelia.

During her fellowship at MIT’s Center for Advanced Visual Studies, the composer actively investigated the so-called otoacoustic emission: additional sounds spontaneously made by the cochlea (putting into lay words, It is like having a tiny musical instrument inside your inner ear). We have learned to ignore such particularities of auditory perception, but Amacher used it as a compositional element in her unique ‘ear-tone’ music.

An excellent example of this is GLIA (named after the glial cells in the brain, which control and support the transmission of stimuli by neurons), a piece for eight acoustic instruments and electronics examining the potentialities of our ears as we interface between two instrumentations. The bizarre cognitive effects that this music evokes are confusing and mesmerising. However, as with other works by Amacher, one of the essential factors here is a live experience. Even the highest quality recording does not convey her sound world’s full depth and multidimensionality.

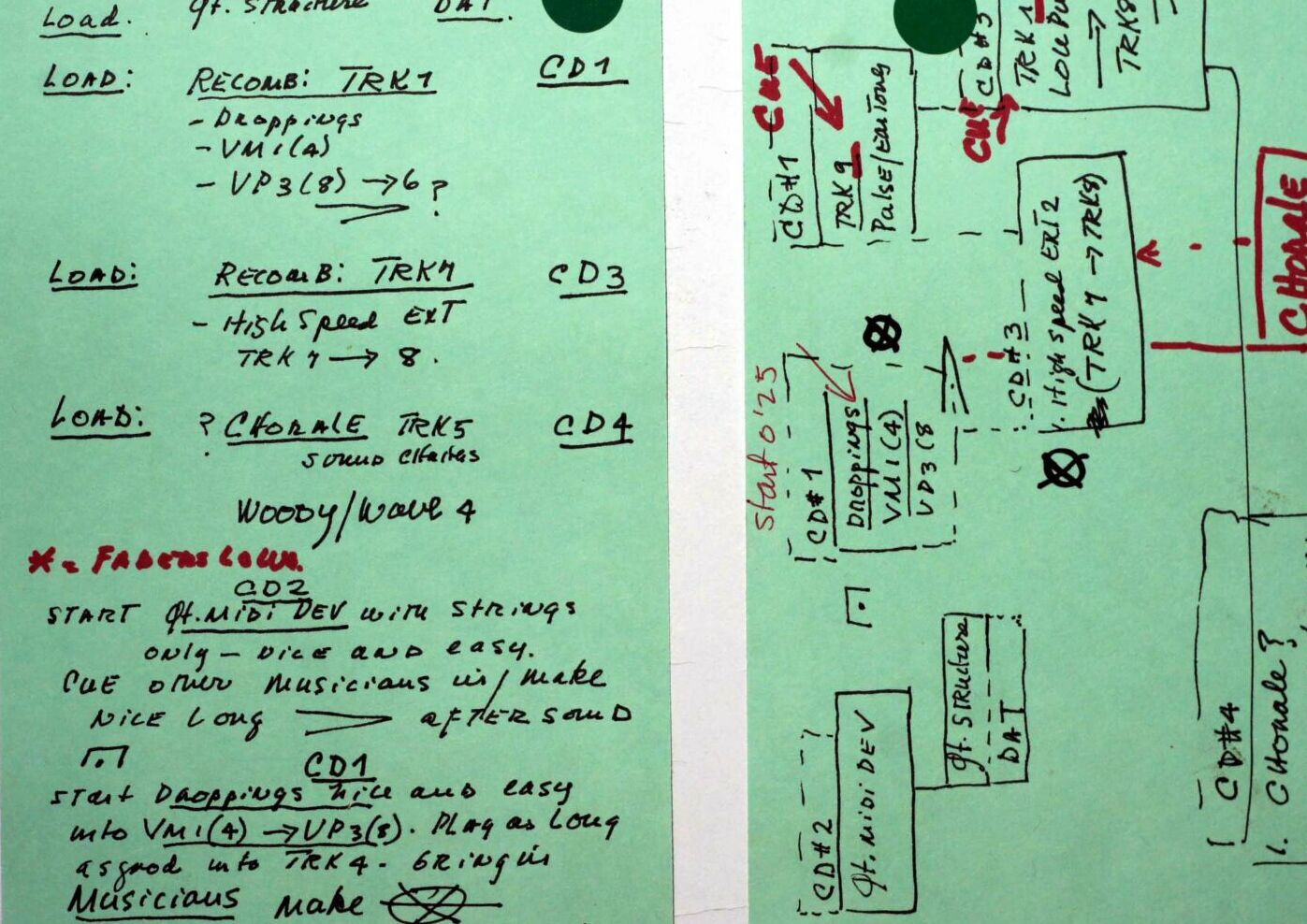

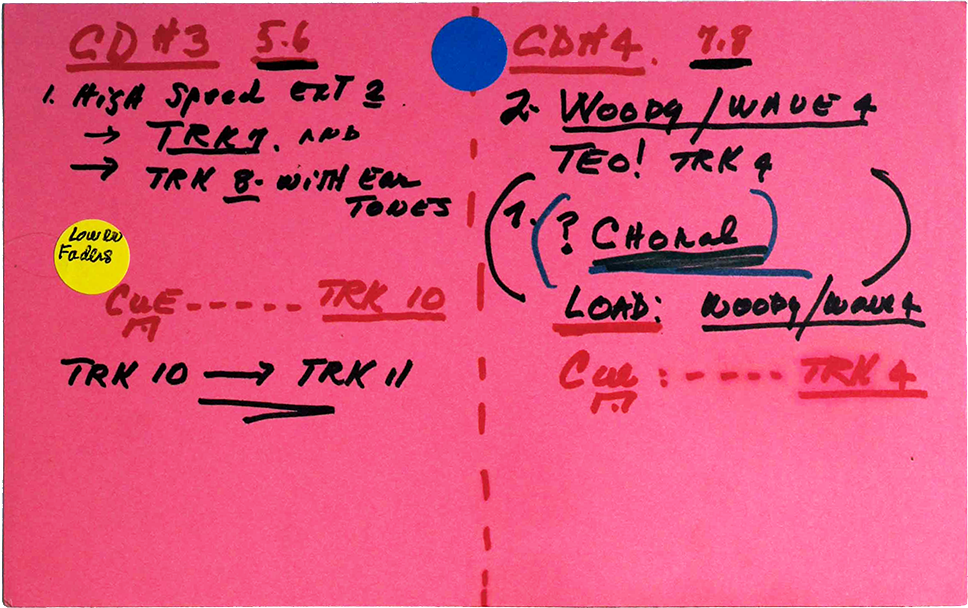

Unfortunately, reproducing Amacher’s creations live is not an easy task and causes much discussion. The composer left little proper documentation of her legacy behind. Even her works that do have instructions of some kind (e.g. scores or recordings) are practically impossible to recreate. The good news is that Amacher’s researchers, friends, and former colleagues are not giving up.

In GLIA’s case, Bill Dietz, composer, writer, and co-chair of the Bard MFA Sound Department, who personally knew Amacher and worked with her for several years, conducted extensive research to reconstruct the piece for future performances.

Originally commissioned for the Zwischentöne Ensemble in 2005, GLIA was presented once in Berlin, directed by Amacher together with the former director of the ensemble, Peter Ablinger and Bill Dietz (the current director). The fact that the composer agreed to create something for an ensemble was exceptional, as since the 1960s, she has refused to work with a concert setting. Instead of any given conventional formats, Amacher created her own: Mini Sound Series, Music for Sound Joined Rooms, and other forms of “architectural staged sound works”.

It was based on personal connections that she agreed [to that commission]. However, she didn’t see it as a great solution or a way out of her approach. Dietz recalls it was more like an experimental engagement for her.

According to him, Amacher took GLIA’s framework from her earlier project, a string quartet for Kronos Quartet, commissioned in 1990 but never performed (and perhaps even completed) for some unknown reason. That piece bore the title The Levi-Montalcini Variations — referring to the work of Nobel prize laureate Rita Levi-Montalcini, which had very much to do with glial cells.

The approach Amacher previously developed and then applied to GLIA focused on three main components: live musicians, electronics and a listener.

In that triangle of relationships, the live musicians, for the most part, guide us [our listening] through what we hear in electronic music, also in the sense of the multiple diverging listening modes that are always happening simultaneously. This is also a fundamental assumption in her [Amacher] way of thinking: that we never just listen in one way — never just to melodic or harmonic material, or just to timbral or semantic layers, Dietz explains.

Amacher considered listening a ‘contingency emergence phenomenon’ involving different modes of perception. The composer wanted listeners to explore their bodies’ capacity for sensations, so she asked the musicians to double the additional sound produced by our ears.

In addition, Amacher strove to present sound as a physical phenomenon. Bill Dietz recalls that when she came to Berlin to work on GLIA, along with the conceptual idea, she also brought a notation in which sounds were described as entities.

Her “sound characters”… She knew them all intimately in the sense of the different listening modes that they evoke. And based on that she could notate. For instance, ‘ok, during this track called ‘Woody,’ this happens, and your ear is doing this, so instruments should play this…’ There is a fixed set of potential materials musicians can play to help listeners identify what all is going on in their listening to the electronic sounds.

Like GLIA, the rest of Amacher’s practice goes far beyond traditional Western composers. For example, she strongly opposed the very idea of a work in its classical Western sense, as well as fixed-form electro-acoustic composition.

She was not interested in sound as property or repeatable possessive quantity. You can hear this very radically in her early City Links series, in which entirely different sounds constitute iterations of a single piece. What made those 100% different-sounding pieces [with the same name] a ‘work’ had nothing to do with particular sounds but with specific questions about modes and forms of presence that she was trying to understand, Dietz states.

Without a doubt, this idiosyncrasy of Amacher’s vision is what one wants to convey when it comes to the posthumous life of her legacy. However, this can be more challenging than reproducing the composer’s works as closely to the original as possible.

Even if you take the same loudspeakers and put them in the same space, with the same angle as she did, would this be of any interest other than purely academic? Bill Dietz is sure it’s not. Everything she tried to do during the 50 years of her career was opposed to standard archival methodologies… made for standard work. To impose that kind of logic on her work after her death would be totally against her spirit.

As well as his colleagues from Supreme Connections (a group of Amacher’s friends, collaborators and students), Dietz is more focused on replicating Amacher’s methodology, drawing on the so-called idea of conscious interpretation:

To various degrees, we have understandings of the modes of listening she might apply to a given situation. So we try to apply what we understand of her methodology in a new situation, activating her sound characters and materials in a new space. For now, I think this is the best we can do to present her work without her. But we can never say this is a work by Maryanne Amacher. Instead, we have to say it is part of the work of Maryanne Amacher.

Of course, not only GLIA found a second life after the composer died in 2009. For example, the aforementioned Supreme Connections presented ‘interpretive’ versions of Amacher’s various installations and music pieces, including an episodic iteration of the Mini Sound Series and a two-piano piece, Petra.

Interpretation has always been an important and integral part of art practice, aimed at expanding our understanding of the work and its artistic value. And although Amacher herself would hardly have been interested in any re-staging formats (according to Dietz, at least), within the posthumous exploration of her sound practices, this approach certainly acquires some strategic importance.

After all, performances such as GLIA, along with the composer’s archive at the New York Public Library and books like Wild Sound: Maryanne Amacher and the Tenses of Audible Life (Amy Cimini) and Maryanne Amacher: Selected Writings and Interviews (Amy Cimini & Bill Dietz), could yet become great inspirational sources for generations of artists and scholars.