Interview by Isabella Ampil

One week after receiving a degree in architecture with maximum distinction from the University of Chile, Nicole L’Huillier started a band called Cóndor Jet in search of novel creative inspiration. She has been playing the drums for the band ever since, growing alongside the group over the years rather than leaving it behind as a relic of her college days.

This love of sound – of making, manipulating, and sharing it with others – permeates L’Huillier’s life, following her home from her work as a research assistant at the MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) Media Lab.

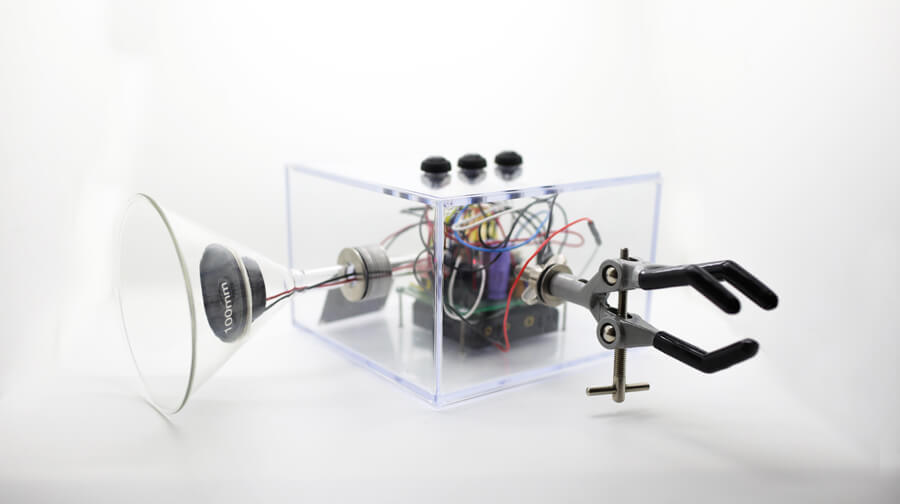

She has even worked on a project to share music in space, designing a futuristic instrument called the Telemetronthat, is designed to make music in zero-gravity conditions. It uses gyroscopic “chimes” that spin inside a clear dodecahedron to translate their movements into sound.

L’Huillier presented on the Telemetron at Sónar + D’s Making Music in Space panel alongside Marc Marzenit of Barcelona and Albert Barqué-Duran of London, creators of the Zero Gravity Band. While the ZGB does not actually operate under zero gravity conditions, it uses an immense dome and shows sound and light to give the viewers the impression that they are untethered to the earth.

At MIT, where L’Huillier works with the Opera of the Future group on projects that advance musical composition, performance, and production, she has found another creative community, not just among her Media Lab team but also in the Hot Milks Foundation, a collective composed of MIT creators. Commissioned by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, the Hot Milks Foundation exhibited a series of beautiful performance pieces over the course of the 2016-17 season.

Partition exists as a set of pastel-coloured parallel benches. As pairs of people come in and take their seats opposite each other, vibrations and infrasound waves (outside the human range of hearing, with frequencies lower than 20 Hz) communicate messages across the aisle. Some vibrations are interpretations of human emotion – laughter or sobs; others capture the rhythm of a song or translate a whispered message. Basing their creation off of biological research into animal communication, the Hot Milks team explores the capacity of inaudible waves to influence the emotional states and relationships of humans who come into contact with them.

Another work, the Affective Induction Spa, plays with light, vibrations, placebo pills, and bone conduction (the transfer of sound via vibrations in bones of the inner ear) to elicit relaxation in its participants. The cheerful, ironic, and bubbly pink brochure accompanying Affective Induction Spa markets the spa as a way to relinquish our happiness to the capabilities of machines. After all, it says, the rest of our lives are controlled by machines and algorithms, from the social norms of Facebook to the uneven dispersal of truth online. “The future is Bright and Controllable!” boasts the brochure as it sells a quick path to happiness, in a caricature of the modern self-help book. At the same time, it conveys the authors’ deep resignation to a world governed by automated decision-making.

But the spa description that lasts on the artists’ sites takes a more sincere tone, serious yet infused with optimism. Art, so the Hot Milk Foundation would have us believe, is the last lens through which we can appreciate existence without measuring or controlling it.

Artist, musician, and architect. You have a multidisciplinary background which you combine in the most surprising ways for your projects, aiming to explore spatial experience, perception and the relationship between sound & space. How and when does the interest in all these disciplines collide?

I have been mixing things and creating disciplinary hybrids since very young. I started to play and make music as a kid, first of all as a drummer and then moved into the electronic world and my love for synthesizers. At the same time, I was always learning about photography, writing poetry, and painting. So I was always doing plenty of things that were in constant dialogue.

Later, when I got into architecture school and during my path as an architect, I learned or started to combine things more balanced or with more awareness. However, I think that intuition is really important in these processes and can never be (or should be) absolutely planned. As a professional, I was running an architecture studio back in Santiago de Chile, performing and touring with my band and creating interactive and perceptual art installations by myself or in collaboration with other artists, engineers, designers, and musicians. This was super interesting and inspiring every day.

But at the same time tiring and very demanding since I was like this fragmented person, or many persons at the same time (crazy! I know) or architect by day, musician by night, and artist on Sundays. So I decided to push for what I wanted to do and build a professional career that mixes everything. That’s when I decided to go to the MIT Media Lab for a Master’s and explore what could happen if I focus on a completely hybrid way of working. It turns out that I found myself during this process.

I even finished my master’s at MIT and stayed as a PhD student, and Research Assistant at the MIT Media Lab turns out that I discovered that I love to do research too. Now my work is a dynamic mix of art, music, science, architecture, theory, and technology, opening more questions than answers, delivering more wrongs than rights… and in all these intersections, I find my happy place as a very curious human.

Your most recent project, Tardigrade Radio, takes the name of a microorganism, one of the most resilient known animals with individual species able to survive the most extreme environmental conditions. What attracted you to Tardigrades to incorporate them into your work? And what was the intellectual process behind this project?

Tardigrade Radio is a very dear project to me. Because it opens up dialogues with other-than-human agents and focuses on giving a voice or a presence to almost invisible beings and microorganisms, this piece started by identifying social structures and shared knowledge about research developed at MIT. I wondered how we could create channels to share information and break the secrecy of some laboratories in an institution like this one. There are a bunch of open public spaces here, so the idea was to create what I call “Parasitic Radio Devices” and disperse them all over the public spaces on campus.

These devices are creating a network system to host pirate radio broadcasts. So they are the infrastructure for using sound as a way to open the skin of the buildings and reveal things without walls. In some way, using sound and radio as an invisible architecture, creating a “sound spill” and blurring the boundaries between inside and outside, lab and nature, fiction and reality. And also, by doing so, reappropriating the airwaves space that has been drastically regulated, institutionalized and privatized.

So by running interviews, visits and sneaking in some labs, I got into the habitat of some microorganisms and bacteria and fell in love with the Tardigrade. So they became the symbol of this project, and the first radio pieces were 3 compositions for them. The 3 compositions are constructed as non-linear narratives. One is a sonic portrait of the Sculpting Evolution Laboratory at the MIT Media Lab, exposing the Tardigrade’s new habitat, its new nature, the only one it knows. And then, it is brought outside to the real nature by being diffused on the hybrid parasitic radios disseminated all over campus.

Other composition reveals 0.1% of the Tardigrade’s genome sequence scaffold. This is a 5740 character string of As, Cs, Gs and Ts that create an arpeggiated sequence in A minor 7 chord. Then the last composition is a whispers choir that narrates the story of how Tardigrades accidentally became an invasive species in outer space.

At Sónar, you present the Telemetrón, an experimental musical instrument made to perform music (and explore poetic possibilities) in zero gravity conditions. What were the biggest challenges you faced in its development?

We (me and my good friend and collaborator Sands Fish) had all these plans and ideas of how Telemetron would behave. We prepared a lot before the performance and thought about gestures, movements, and ways to play this instrument. We even thought about choreography. To realize that when you fly in zero gravity, everything changes. Your body needs to relearn how to perceive and how to be. In such an alien environment, we are more aware of ourselves than ever, re-calibrating, re-being.

And this is extremely hard and fascinating! In this medium, we become matter and enter another dimension where humans and matter need to relate in a more transversal and intimate way. And things come to life and are more vibrant than ever. And the Telemetron opens up a dance between human and non-human bodies. We also faced a lot of technical challenges.

There were tons of regulations to be able to fly the Telemetron, technical aspects, safety constraints, mechanical and structural requirements, and even the communication protocols needed to be very well thought out, and a lot of variables and details to be considered. We overcame tons of challenges to create a musical instrument that is under the regulations of the Federal Aeronautics Administration… This is the most legit instrument I have ever made.

You are also a PhD Student and Research Assistant at MIT Media Lab – Media Arts & Sciences. Could you tell us what Opera of the Future is about?

The Media Lab is an academic Research Laboratory at MIT, and it hosts the graduate program in Media Arts & Sciences. It comprises around 27 research groups (this number changes annually). The groups are very diverse, fluctuating from robotics, neuroscience, design, music, art, prosthetics, intelligent cities, biohacking, evolution sculpting, and many more. Among these, Opera of the Future is the research group where music is at its centre, but we work on various perspectives too.

Tod Machover leads the group, and it’s very diverse. All the students and researchers have very different backgrounds, interests, and focuses, which enriches how we work when we all come together or discuss things as a team. Different types of projects are developed here, such as a Robot Opera, Software for Collaborative Composition, City Symphonies and different tools for creativity in arts and music and the creation of installation and experiences. For me, the group unites us by understanding music as something that connects us to each other and our emotions.

As well as using art as a tool for change, projecting futures, fostering engagement, and for opening new narratives. Opera of the Future has been to me a space to explore, experiment, break, make, connect, re-shape, grow and explode.

Sónar+D this year is largely focused on space and communication. With your practice, what have you learned that space can teach us about sound?

Well, a lot, and since this is such a new “territory” of exploration, so many things are yet to come and new questions to be asked. For me, the most beautiful thing is actually really simple: sound is not only sound, but it is information, data, vibrations, and resonance. So sound in some way “is” by “being” with the matter. With this in mind, sonic signals sent to outer space hoping for some communication and an answer are independent of the sonority of perceptual aspects of the sonic and listening.

They are important because sonic messages are frequencies and vibrations and are the best hope to get in touch with other intelligent forms that can decrypt a signal of interference and find the message. Anyways, I love that sound is important not only because of sound but because of its material “in-betweenness”.

On another layer, I think that the space exploration scenario is very valuable because it opens up a series of new narratives, possibilities, challenges and poetics, not only towards sound. But most importantly, about everything and the possibility of being a place to imagine diversified futures and imaginative projections, it opens up a scenario for a whole new set of potentials and possibilities.

I am part of the MIT Media Lab Space Exploration Initiative, where I have been working on different pieces and projects to explore possible experimental forms and implications of art, expression, and culture as humans migrate to outer space and how to start creating an inclusive and diversified space future, where the multiplicity of voices can be included.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Being right. I like to embrace failure as a powerful work tool. I fail all the time, and I learn a lot, and then I try again, and again, and again and in the process, I learn new things, completely unthought scenarios unveil. I think it is super important to be flexible. At least for me, it is essential to work towards many possibilities and to have explorative processes. Perfection kills it for me. It’s too safe. It’s too clean, it’s too much, only 1 thing.

You couldn’t live without…

Sound; I am a sonic human.