Interview by Lidia Ratoi

Yunchul Kim lives between Berlin and Seoul. He creates art somewhere in the boundary between technology, chemistry, physics, robotics, astronomy and music. Kim admits that he researches the artistic potential of fluid dynamics and photonic crystals in the context of magnetohydrodynamics.

His utopian pieces have won him the Arts at CERN award, but to talk about Yunchul’s accomplishments seems redundant. However, it might be even harder to discuss his work. So many words and comparisons are needed to try to capture it. It’s somewhat steampunk but uses state-of-the-art technology. It’s like an Umberto Eco book or a David Lynch movie.

Yes, it looks like a movie set. But also like the real-life laboratory of a brilliant scientist. It manipulates materials in such a natural way that you take them for granted without considering all the research behind it. But that’s the definition of good art. You shouldn’t tell how much the piano player studied or the dancer rehearsed – it should look like it just happened spontaneously.

Usually, art is a dream, something surreal, but through his scientific approach, Yunchul Kim makes real technology the ultimate art form. It unfolds before our eyes, and posing questions about it is futile. In pieces such as Cascade, Kim makes his art sing – the machines have their own rhythm and pitch, and the circuit works in a distinct way that produces a soundtrack for the story he includes us in.

Educated as a musician – his art is alluring, magnetic, fascinating, and humble. The kind of modesty that comes only from higher beings. The contraptions and materials function independently, following the rules of physics. Or metaphysics – hard to tell. They work perfectly, uninterrupted, seeming like they have existed since the dawn of man. They seem to invite us to gaze at their beauty, being so aware of their perfection that they have no other choice but to accept our own human imperfections.

Works such as Effulge, which looks as if the gold of El Dorado fell into the hands of a robotic researcher, still have this extremely approachable and inviting aspect. You want to go close to the pieces. You want to observe every single detail (which is executed flawlessly). You want to see the nanoparticles changing as they travel through tubes filled with hydrogel or other types of liquid. You want to experience first-hand the changing light patterns refracted through the materials.

Yunchul Kim waltzes with our minds and souls in a way that only someone with such a deep understanding of things could. His multidisciplinary approach transforms him into a wizard of senses, playing effortlessly outside the bounds of regular imagination.

Dawns, Mine, Crystal is your first UK solo exhibition. The exhibition comprises installations, paintings and sketchbooks and premieres your new work Cascade (2018). It also features Triaxial Pillars II, which looks at the possibility of controlling light propagation through colloidal suspensions of photonic crystals. Could you tell us a little bit about the intellectual processes behind them?

This exhibition features three works that together form the new commission Cascade. Cascade includes the 41-channel muon detector Argos, which presents cosmic particles received from space, triggering the kinetic movement of its counterpart, Impulse – the non-pulsating liquid transfer system controlling fluid flow. The third part, called Tubular, is the visual enactment of this microfluidics and physically shows fluid flow.

In Cascade, fluids are constantly disappearing and re-appearance due to the materials’ common refractive index. All this ‘controlling’ is possible because all three components are intimately connected to each other. And as these machines, objects, and cosmic events interact with one another, the viewers experience this interweaving phenomenon as a work of art.

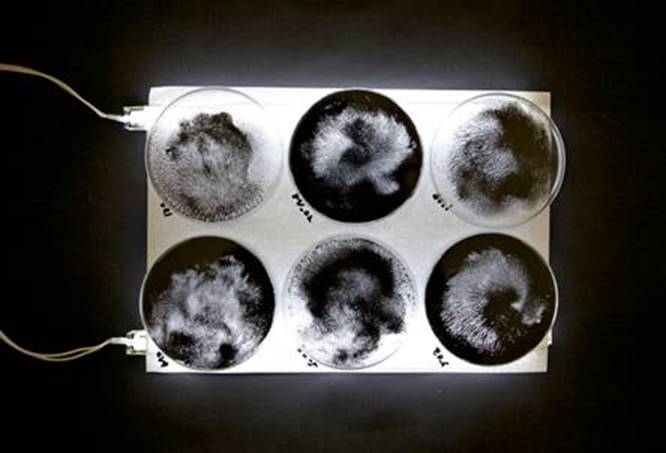

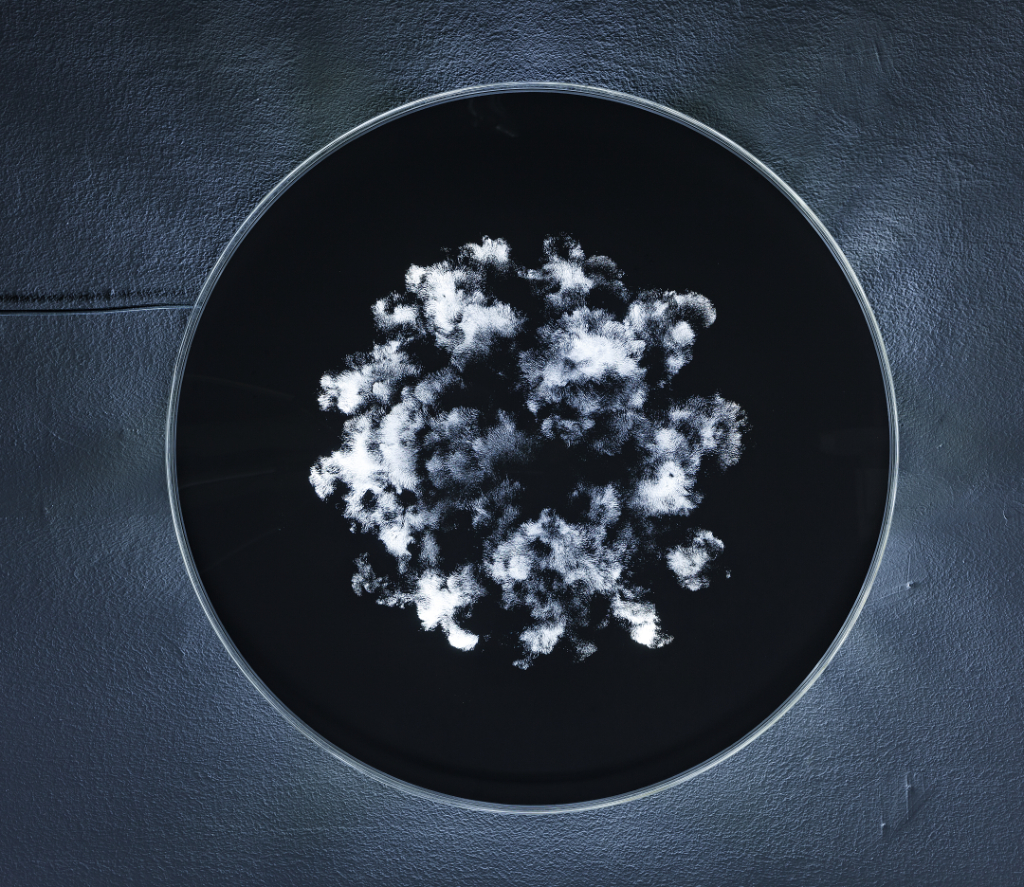

Triaxial Pillars II is a fluidic kinetic installation consisting of multiple planetary, helical structures with twenty-three axes and a double acrylic cylinder filled with nano-sized photonic crystals. Four air diffusers in the cylinder, controlled by solenoids, spout out air with various pressures in helical patterns, lifting the metal particles sunk by gravity to the top and recording their movements on the surface of the fluid.

Cascade won last year’s residency at CERN. How did this residency reshape the way you approach the art form?

Most of all, it broadened my cognitive understanding of nature and space. The conversations I had with various scientists and the opportunity to discuss the fundamental questions about space, matter and particles with them became an important departure point for widening my thoughts.

More importantly, the colossal machines I encountered and the intrinsic aesthetics of the laboratories became a direct inspiration for my works. In fact, watching various documentation of the workshops with muon detectors at CERN was fundamental to the development of Argos in Cascade.

As an artist and composer exploring the properties of matter, the potential of fluid dynamics and natural processes, what is the role of sound in your art pieces?

I came to the visual arts after initially having studied music. The works I now make are time-based, so dealing with these events is not actually too different from when I did the music. Even though I do not actually create sounds, the kinetic movements through various devices of my works can be seen as a real-time composition. Various noises are heard when the fluid flows within the devices, which I think can be perceived as having a musical experience. I still work with music, and I anticipate that one day there will be a point when my sound ideas and visual works will meet.

Are there any unexplored artistic fields you would like to take your work into?

I am highly interested in working on the synthesis of sound through chemical reactions. I am actually in the process of experimenting with structural colouration through nanostructures.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Stability.

You couldn’t live without…

Music.