Words by Cathrine Disney

In times when the techno-metropolitan environments (where most of us live nowadays) seem to have disconnected us from our earthy habitats and their seasonalities, it is interesting to discover artists like Karen Miranda Abel. Her art reflects this delicate temporality and ephemeral fluctuations.

Concerned with biodiversity and urban ecology, this Canadian interdisciplinary artist could be described as somewhat of a naturalist. Her transient and seasonal work is a testimonial to the beauty and inner workings of nature.

Abel’s research-intensive, slow art process allows her work to evolve freely and take on its own form, bringing a real sense of time and narrative to each piece.

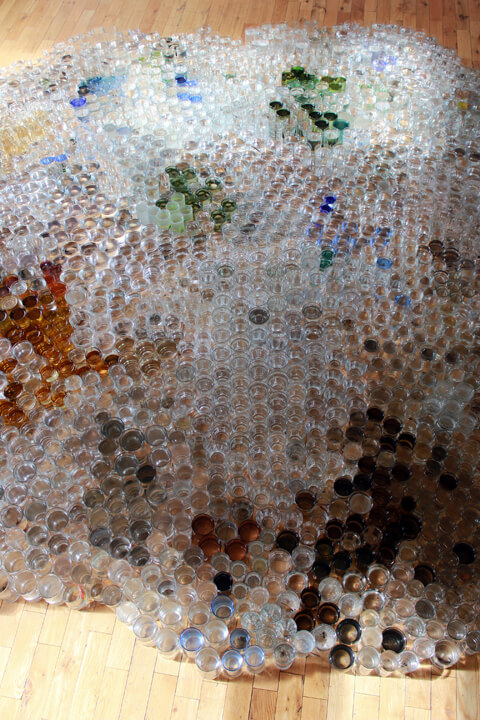

In homage to a key springtime event, one of Abel’s most recent works, Vernal Pool, references the temporary pool of water that provides a habitat for the safe development of natal amphibian and insect species, occurring as a result of snowmelt in a forest depression.

Abel invited over 100 participants from Canada and abroad to collect snow and deliver it in its melted form. Over 1,900 pieces of glassware were donated by family and friends or salvaged from thrift stores to complete the work. This creates a tangible connection between the water we drink every day and the water that falls from the sky in the form of rain and snow.

Ecology and diversity are two of the central axes of Abel’s body of work. With Vernal Pool and other projects, the artist aims to raise awareness and make us think about how water is one of the world’s most critical resources in a natural ecosystem; an ecosystem which is seriously endangered and a big part of the population is without access to potable water.

Your work involves art, science and ecology. When and how did the fascination with them come about?

These themes (in numerous forms and understandings) have essentially pervaded my life and thoughts for as long as I can remember. I think I have always engaged with my surroundings creatively. To have known a strong affinity and respect for animals and the natural world my entire life.

As a child, I would spend days in streams, ponds, and lakes, exploring aquatic life with complete absorption. Some of the places that I remember with such clarity are no longer in existence – bulldozed into the past years ago.

The realization of a project such as Vernal Pool (2014) – where snow samples collected by over one hundred participants from across Canada and abroad were brought into a gallery space to form a pool-like installation – was in a way like coming home to, and honouring, the memory of those formative environments.

What do you expect from the collaboration between ecology and art?

I think of art as something that is experienced rather than simply viewed. I have never understood the widespread use of the word “viewer” to describe one’s relationship with a work of art. Art is visited; like a place. We navigate towards and around a sculpture.

Even a painting in a gallery is approached. I know it to be a spatial, multisensory interaction as a visitor. At times, perhaps a sort of spiritual visitation too.

Working within ecology, landscape, and environment conveys this sensibility about the significance of space and place in art. And I think this is an exciting understanding to stimulate contemporary art right now.

How did you come up with the idea behind Vernal Pool project? What was the most difficult part of its development?

A long succession of ideas and experiences led to the development of Vernal Pool: a participatory art project about place + precipitation (2014). To put it simply, I can say that I was looking to generate a subtle gesture of an ecological event.

I wanted to reduce the idea of a watery landscape to little more than an essence; something elemental. The dynamic interplay of sunlight and time (i.e., light reflection and water evaporation) are essential components of the work.

A vernal pool is a short-lived wetland made by snowmelt, typically forming in a forest depression. This ephemeral springtime event is key to the natal development of amphibians such as frogs and salamanders. I worked on the project with fellow Toronto artist Jessica Marion Barr, who designed a sound installation of Ontario frog calls (Spring Peepers and Gray Treefrogs) for the installation.

I wanted to make a connection between the water we drink every day and the water that falls from the sky in the form of snow and rain. 1,900+ pieces of glassware – all used material salvaged from thrift stores or donated by friends, family and project supporters – have a past.

The individual glasses have been touched by many people over time – held up to mouths for drinking over many years or decades in some cases. A remnant history of those human-object interactions becomes part of the work.

In the same way, asking participants to collect snow from anywhere around the world and deliver it to us in its melted form to be combined into a large body of water in a gallery, was again about highlighting those time/place interconnections. Water is a great equalizer.

At the end of the spring exhibition held in April at Toronto’s Gladstone Hotel gallery, virtually all of the water was returned in some form back to the ground. On the final day of the exhibition, we offered visitors jars of snowmelt from Vernal Pool for watering local urban gardens.

Realizing the project was a great challenge but in the most delightful way. There wasn’t an opportunity to rehearse the installation prior to the exhibition. I had no idea how many people would choose to participate in collecting snow samples during the winter of 2013/2014.

Transporting over 650 litres of water into the space in a very short window of time was a somewhat precarious adventure made possible only with the help of many generous people. At the time it felt like the best kind of creative madness.

The project has now seen a second iteration called Riffle Pool Riffle (2014) in Warkworth, Ontario. In it, water was collected from a nearby creek and installed in a barn as part of an exhibition of contemporary art in a rural setting called Sunday Drive.

Similarly, at the end of the 16-day exhibition, the remaining water (almost an inch of water had evaporated from the glasses) was returned to the creek. A third iteration of this work is currently being developed for an exhibition at a lake-side museum in 2016.

Is art helping to understand scientific/ecological issues or it is challenging what society understands about them?

Hopefully both. I think these intentions emanate from some of my work; however, I tend to avoid the formality of framing my practice in this way. Environment and ecology are alive and (more or less) well in everything we do, in every moment of the day, whether recognized as such or not.

At this point, I think most of my interests lie in curiosity with exploratory questions, rather than arriving at answers.

What are your aims as a bio artist working in between science and art?

I think an artist could spend a lifetime arriving at an answer to this type of question and I especially like that fact. To keep it that way and maintain a sense of mystery in terms of my relationship with my art and its intended purpose.

Science and art exist within webs of knowledge systems that are perpetually evolving. I think my instinct may be to not even recognize much of a distinction between art and science, to begin with, to find such a resolution inspiring (and the rebel in me enjoys its provocativeness).

Ultimately, I see each of my works as a kind of conceptual garden – a viable coming together of interconnected elements and ideas; a cultivation of intention in time and place.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Does creativity have enemies? Only imagined ones, I would think. I can say that being prompted artistically generally works against my way of arriving at any creative juncture. To refer to my practice as slow art. Whenever possible, it is important for my work and research processes to evolve freely; in their own time.

Once I find momentum, I can usually maintain a dedication to my work with intensity – focused on completion through the blood, sweat and tears of artistic production. Perhaps a sense of loyalty in this quiet determination is what some people have connected with in my work.

You couldn’t live without…

Time. Creatively speaking, time is a cherished tool – one that seems undervalued in the present day. It is such a gift to be given (and to give) time for something to evolve in the most free form, whether an artistic concept or a collaborative relationship. Alongside time would be freedom, which I feel is not unlike time.