Interview by Diana Cano Bordajandi

Neus Torres Tamarit is an artist and art director that explores the interaction between art and genetics. Her aim is to evoke curiosity and make science more accessible to the public through bioart. She collaborates at the Tate Modern and has exhibited internationally at places like the Louvre Museum and India’s Srishti Institute of Art Design and Technology.

In 2016, Neus curated Cryptic, an art and science exhibition at the Crypt Gallery in London. She is now curating the 2017 edition, which will be open to the public from Friday 24th to Monday 27th of November. The exhibition – presenting nineteen international artists – aims to explore the connection between art, science and technology.

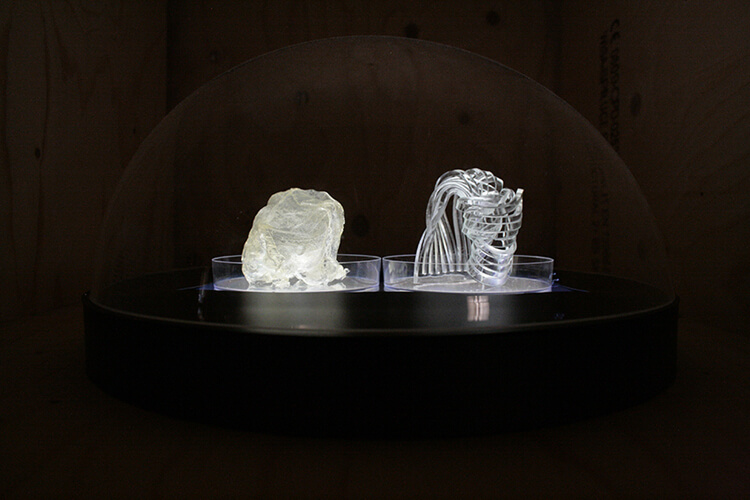

It does so by presenting a diverse collection of artworks and subject matters, such as the synthesis of emotions into sculptural and crystalline forms, mutation mutated into abstracted expression, the multiverse, and many more. Digital and kinetic interactive art pieces, virtual reality, and mixed media installations should also be expected at the exhibition.

Neus has worked on many other projects, creating numerous artworks. She developed a workshop dealing with metagenomics and recombination – which dealt with the principles of how the genomes of the bacteria and viruses that we host can interact with our health on a fundamental level – and collaborated with the Royal Society in their project “Changing Expectations” by creating a spinning wheel – based on a Codon Wheel – for their exhibition.

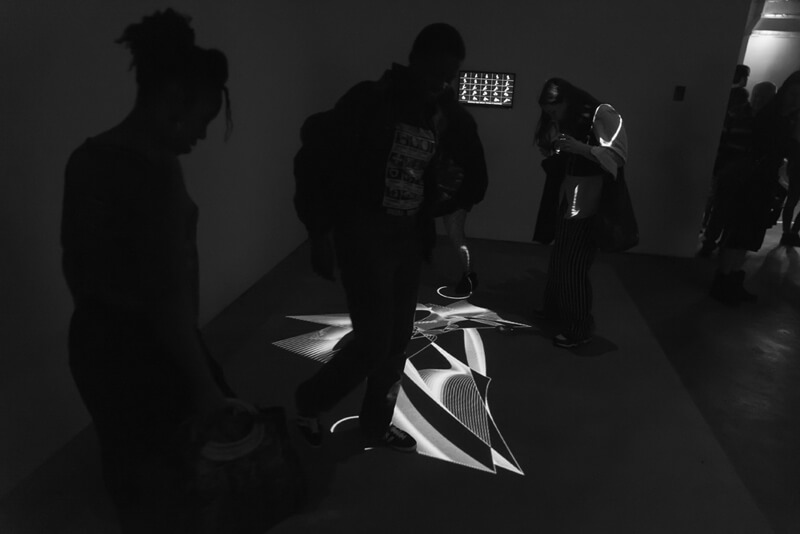

However, Neus’ biggest project to date is Biomorpha (Evolving Structures), her final project for the Masters in Art and Science at Central Saint Martins. Biomorpha consists of a digital interactive installation that aims to explore how the environment shapes organisms over generations. The audience can interact with Biomorpha by entering the field of view of a Kinect camera. A digital organism is situated within a landscape of evolutionary pressure to which it is adapted. When a member of the audience enters the field of view of the camera, they become a new evolutionary threat. The digital organism responds to this by undergoing a series of mutations that change its form to adapt to the presence of the audience member.

Through Biomorpha, Neus creates an emotional response in the audience, allowing them to react to the subject of genetics as a human experience.

Biomorpha (Evolving Structures) is your final project for the Masters in Art and Science at Central Saint Martins. The project explores the idea that an organism is limited by the success of the mutations of its ancestors. Could you tell us a little bit more about the intellectual process behind? How did you come up with the idea?

Biomorpha explores the dramatic evolutionary pressure that can be caused by a sudden change in a species’ environment. An organism that is well adapted to a relatively stable environment can stay largely unchanged for millions of years. In the event of a dramatic disturbance, however, species can undergo dramatic changes in a relatively short time, as there is a high potential for mutations that help it to survive the new challenges that it faces.

The main artwork of Biomorpha is a digital interactive installation in which the audience acts as an evolutionary pressure on the environment that the digital organism inhabits. When people interact with Biomorpha by entering in the field of view of a Kinect camera, the organism undergoes a series of random mutations that radically warp its form, some of which help it become more adapted to the presence of the audience members. Our measure of adaptation is simple; the closer the organism is to the audience, the better adapted it is.

Biomorpha is the result of a process that I started in 2015 before starting the Masters’s in Art and Science when I started to learn about genetics and to collaborate with my partner Ben Murray, a computer scientist with a background in video games, medical imaging and bioinformatics. As part of the collaboration and my artistic practice and goals, I have been learning programming and maths, which is being quite challenging as my background is solely in arts.

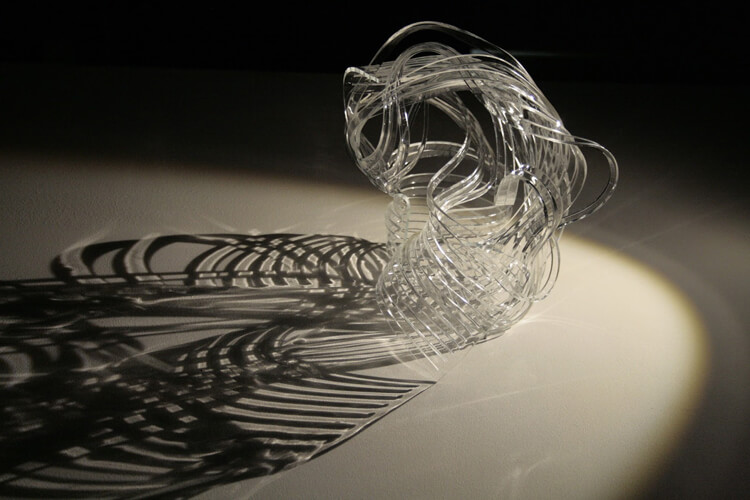

This project builds on our installation, Confined Mutations, which was inspired by the book, Why Evolution Is True, by Jerry Coyne. We created three animations based on a motif that I created while learning how to program. The book discusses the recurring laryngeal nerve in mammals, which runs from the brain to the larynx in a loop around the top of the heart. Evolution cannot create a mutation that untangles the nerve from the aorta to make it go directly to the larynx; any such mutation would be overwhelmingly unlikely to happen. Evolution works in gradual, accumulated mutations, and a break in either of the two systems would be very likely to be fatal to the unfortunate recipient. The ability of evolution to create new beneficial mutations is constrained by the legacy of successful mutations that make us what we are.

We also invited two contemporary dancers from the London Contemporary Dance School, Aimee Dulake and Jessie Richardson, who performed a series of improvised dialogues with Biomorpha. It was very interesting to see the continuously evolving dialogue. Also, as part of the research for the piece, I had continuous conversations with Dr Max Reuter, from the Department of Genetics, Evolution and Environment at UCL, about the evolution and genetics concepts behind the piece as my objective has always been to be as accurate as possible to the science behind the artwork.

After graduating, what directions do you see taking your work into?

I started with a new artistic direction slightly over a year before I started the MA at Central Saint Martins, so really, the MA was an opportunity to help me understand whether this new direction could really work. It showed me that this is a very interesting field, and it has triggered in me a passion and great enthusiasm, so really my artistic direction after the MA is a continuation rather than a new direction.

I am interested in continuing developing the model for modes of interaction between art and genetics that I created as part of my theoretical research for the master’s; this model to analyse art about science in terms of critical, interpretative and representational modes, gave me more insight into my artistic practice and the great interest in bridging the gap between science and public through art.

I will continue developing digital interactive installations about genetics and evolution and explore how the artistic method can help make difficult scientific concepts more understandable. I have recently started a residency as an artist with Dr Max Reuter at UCL and his evolutionary biology lab, which is very exciting. I have access to the laboratory to fruit flies and to the experience and knowledge of Max, Florencia Camus, his post-doc and Filip Ruzicka, his PhD student. It is an amazing opportunity to continue my career.

I am also continuing to develop my artistic practice as a curator, and I am organising the second edition of Cryptic: Art and Science at the Crypt Gallery at Euston Road. This year I am curating the artwork of 19 artists, including myself and my collaborators, and I am looking forward to the exhibition, which runs from the 24th to the 27th of November. I plan to continue to collaborate with Ben and create more ambitious digital interactive installations that coordinate virtual reality and projections in reality.

What is more important: to take or not to take yourself too seriously in order to be creative?

I’m not sure it is about whether I take myself seriously or not. I guess that, for some artists, it is important to ‘let go’ in some way to find their creativity, but I have an approach in my creative practice that I follow to stay creative. My artistic practice involves me shifting back and forth between form and concept, to try out many things and not end up blocked in the process. This results in artworks that are sometimes very different from what I initially thought I was creating, or having concepts that get matched to forms later in the process rather than having a grand vision of the artwork straight away.

So I suppose that I think it is important to take oneself seriously but to have room to be more informal; having space to try and test ideas is very important; some ideas my initially seem uninteresting, but they get more potential when developed a bit further and vice versa. Having room for research, failure and experimentation is vital and helps to narrow down and select what is more important than what is not.

You also make me think about my collaborative relationship with scientists. They all take their research incredibly seriously; what I want to do as an artist is help them see their discipline from a different perspective to become creative in an artistic way.

If you could visit someone else’s mind, who would it be?

This is a very difficult question! I think if I had to choose only one person, I would choose Leonardo Da Vinci. I think all his work is fascinating, and he worked in a time that didn’t have the same distinctions between disciplines, so was free to apply his genius to everything that interested him. I would love to understand his creative process and how he was able to be both so endlessly creative and so skilled.

One for the road… What are you unafraid of?

I am unafraid of challenges. I decided to explore my new artistic practice and study the two-year MA in Art and Science to see where it would take me. I changed my previous artistic practice quite radically and although it is a learning curve and I feel I am still near the beginning of the process, I am committed to continuing on this path.

I’m unafraid of addressing scientists and talking with them about their subject from what is often, for them, a completely new point of view. I’ve had a number of interactions with scientists who openly express their scepticism about having an artist in a dialog about science; instead of taking it personally, I take it as a challenge to help them see their own discipline from a viewpoint outside of their daily research.