Words by Lula Criado

Interdisciplinary designer Sarah Daher explores the relationships between humans, nature and technology and imagines future scenarios in which humans will engage with plants as intelligent beings. Communication is ubiquitous nowadays; the information superhighway with networks, digital communication and interactive services has made this possible but, what if we go a step further and messages can be sent through the air by releasing chemical molecules?

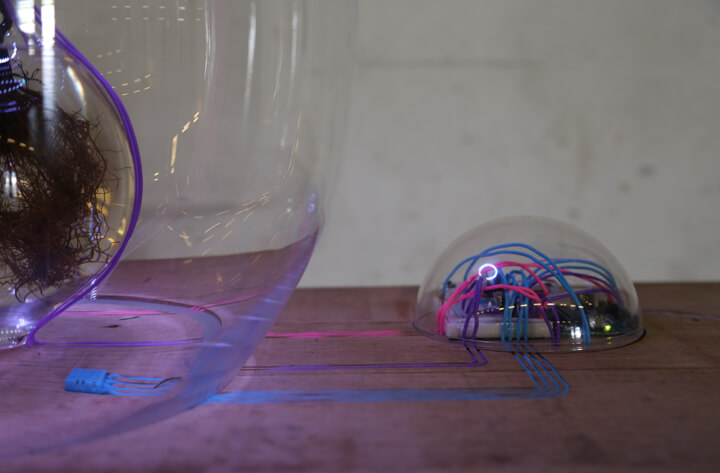

With the ‘what if’ question as starting point, Daher developed Air Culture, her graduation project from Design Academy Eindhoven which imagines how the future will be if we gain the ability to communicate through the air.

Air Culture, is an interdisciplinary project in which several different disciplines and fields are involved. Science with pharmacognosy and chemistry, nature with plant neurobiology and aromatology, and technology to design future scenarios all challenge how we related to our environment.

Flying gardens suspended in the sky that provide cities with autonomous ecosystems or plants as an extension of the human body growing in a symbiotic relationship are just a few of the thought-provoking future scenarios Sarah Daher has designed in previous works.

You are a designer working at the intersection of design, science, nature and technology. When and how did the fascination with them come about?

It all came in different parts. Nature was always a fascination. As I grew up I saw how our technological development was disrespecting and abusing our natural environment. But technology also brought us so many unimaginable benefits.

Therefore I started to question; how the same technology that we use to dominate the natural environment could be used to empower and improve nature.

The scientific aspect came when I first saw Stephano Mancuso talking about plant intelligence. Then I found the scientific field of Plant Signaling and Behaviour, and what first started as a personal interest, suddenly became inseparable from my creative practice; a never-ending source of inspiration. Nevertheless, this is a conflictive practice.

Knowing that plants communicate and even have some sort of intelligence shakes the physical and biological bridges we have built to separate us from them. It involves many cultural and philosophical values that shape our perception of the vegetal kingdom.

That’s why design, as an in-between practice, can intermediate and through scientific research question this ingrained values acting as a changing factor in reality. By envisioning possible futures design can trigger our imagination and stimulate a different perception of reality.

What are your aims as a designer working in between them?

My aim is to re-invent our relationship with plants. That requires different strategies and different fields of work and research. But for now, the first aim is to disclose an evolved understanding of plants -that accomplish with modern scientific findings- as dynamic, intelligent and communicative beings that we can collaborate with.

Secondly and most challenging is to stimulate scientific research. I would like to develop a scientific field that investigates the chemical exchange between humans and plants and its possible consequences. There is a lot of research done regarding plant-plant and plant-insects; which is mainly focused on agricultural advancements.

A research field focused on plant-human exchanges can open new possibilities not only for health care and medical interventions but it can also provide with new ways to perceive and experience nature.

The starting point of Air Culture is to question the way we relate with plants and the value of air. You propose to create pockets of personalised air with health benefits. Could you tell us a little bit more about the conceptual frame behind it?

Plants communicate in different ways. One of the most effective mediums they use to interact with their surroundings is the air. They synthesise chemical volatiles and release them as airborne messages to aware other plants, and attract or repel insects and herbivores.

While researching those compounds I found that they also have an impact on our organisms and therefore we already harvest them for pharmaceutical purposes. So, if specific plants are constantly releasing into the atmosphere the chemical compounds that we usually harvest for medical purposes, this means that living plants can have a much broader impact on our lives than we expected.

So rather than considering plants as passive resources, I propose a system where we acknowledge plants as intelligent beings, that sense and respond to environmental changes and that these chemical responses consequently alter the properties of the air.

This air can be harvested or directly inhaled by us and would have different impacts on our physical and psychological well-being according to the plant species, the life cycle of the plant and the environmental inputs.

Technology enhances this chemical production providing changes in light frequencies, temperature, humidity and water supply in an enclosed environment. The system can be programmed to stimulate the plant during a certain period of time which is ideal for the production of specific compounds to the detriment of others.

In this way, we become aware that plants have a chemical vocabulary and that this volatile emission can affect and possibly improve our human capabilities, as in the case of Rosmarinus officinalis, in which some compounds stimulate neural activity, increasing memory, cognitive performance and mental sharpness. It also tackles a delicate and controversial idea of the commodification of air.

We already commodify most of our natural resources, and fresh air is already becoming scarce in some parts of the planet. And this is a very critical point. A lot of people are already aware of the benefits of organic food and eating healthy but no one really pays attention to the air.

So I try to highlight the importance of air and that plants not only produce oxygen as discovered in the 18th century, not only purify the air as found in the 20th century but they also add chemical particles or gases, being able to change the atmospheric properties around it. So I want to propose the idea that air also has a nutritional value that can influence our organisms.

I imagine how specialized air consumption will become part of our culture and be incorporated into our daily lives. For me, “Air Culture Lab” is more like a display of how the system works but I envision how air production in the future will take part in the urban and public space and how it can be incorporated into our existing building infrastructures.

It is a speculative approach but I believe we are not too far from this reality and in fact it has a lot of economic potential. What if in the future the same way we already farm for food we will have to farm for air?

What directions do you imagine taking your work in?

I want to question more about the role of vegetation in the urban landscape. We need fundamental changes in the way our cities are working. I believe there is much more we can benefit from plants and plants from us.

There is a chemical and physical bond between our human physiology and the physiology of a plant. If we see vegetation as our partner we will be able to recreate our living environment from a micro to a macro scale.

Plants function as a modular and interconnected network. They produce and share resources and most important, there is no concept of waste. If offered the right conditions, plants will work within a cycle of abundance and their inherent regenerative capabilities can restore even the most degraded and polluted areas.

If we provide them with the infrastructure they need to perform and combine it with effective technology they will, if not solve, at least be able to minimise most of the social and environmental challenges we face with urbanisation.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

I don’t consider enemies, everything that challenges us makes us grow. But my biggest challenge could be pre-defined concepts and stigmas that block us to evolve a more integral perception of plants and develop the subtle areas of our consciousness that are in connection with other species.

But thankfully the scientific field is also taking a step toward the unknown as is seen in the work of Rupert Sheldrake and Fritjof Capra which are bringing a more holistic approach to science.

You couldn’t live without…

First of all air, right? But besides our physiological needs, I think I couldn’t live without love and passion. These shouldn’t be feeling that we save for our closest ones. Love can be in everything and everywhere. To do something I need to feel it from inside.

Whatever I do I want to do it with a belief and taking into consideration the circumstances around me. I don’t want to work for selfish purposes. I want to dedicate my life to a common future where we can evolve in connection and collaboration with other forms of life.

I’m really fascinated about plants and I’m very excited about how the scientific field is unveiling the amazing features they have and how through my design practice I can have the freedom to imagine and propose future realities. And the most exciting part is that I’m sure this is just the beginning. There is a lot to prove and a lot to discover!