Interview by Miriam Ahmad-Gawel

We often find the world of coding and electronics abstract and inaccessible. This is a statement I am sure many would agree with. Even to those within other STEM fields, information technology can seem daunting by the nature of its relative novelty and exclusivity. The public’s understanding of DNA, for example, is likely better than that of a gigabyte.

But what if this barrier to understanding isn’t because the average layperson is incapable of comprehending the nitty gritty, logistical aspects of IT, but rather because as the field stands today, it is riddled with jargon, and functional application of the technological dictionary is difficult for the unversed.

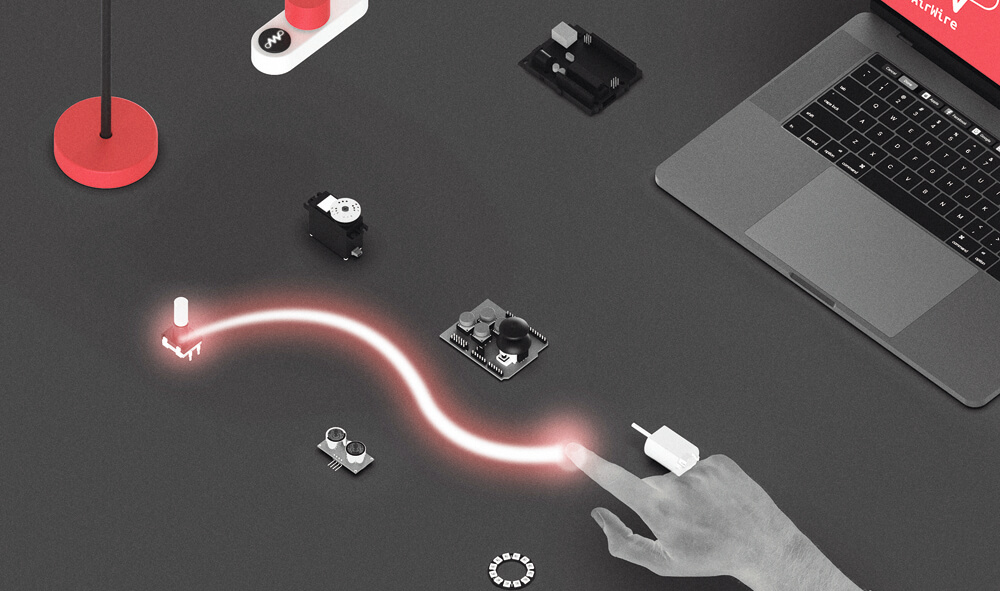

This proposition and quote were taken from CLOT’s interview with Viraj Joshi, an industrial designer and creator of AirWire, the world’s first prototyping platform that is dictated by a hand gesture. A relatively minimal-looking apparatus, AirWire incorporates a camera that picks up on various hand gestures that translate to programmable coding and then applies the desired code and program to the system being worked on. This happens in real-time, allowing users to work and see results concurrently.

Joshi strives to combine design and technology on a truly innovative plane. His work centres on speculative themes and emerging technology; he doesn’t design for today but for days to come. And that is exactly what AirWire sounds like, something from the future. Entirely conceptualised and created as part of Joshi’s dual Innovation Design Engineering master’s degree shared between the Royal College of Art and Imperial College London, AirWire is an accessible programming means for all.

Crucially, the invention enables. It provides access to a field that is often shied away from because it seems intricate and complicated. Joshi’s work might allow someone to create the very specific flashing lights display they would like for their Christmas tree without any linguistic knowledge of information technology at all.

Herein lies the beauty of Joshi’s work: as the tech world expands quickly, many of us struggle to keep up. Innovations that bridge gaps between the least IT-savvy and the leading industrial designers allow for shared knowledge. The more knowledge that can be shared, the more we can grow and adapt and improve as a species — the more we can include, the more we can do. Information is power, and emerging technology seems to make power limitless.

For those unfamiliar with your background, could you tell us a bit more about your aims as an artist and a designer?

In the last couple of years, I have become a melange of a design fiction writer and a technology enthusiast – building on a foundation of classical industrial design practice. This was a conscious exercise – to become more of an “inventor” and not only a designer. I spent the last 2 years of my master’s learning electronics, physical computing and emerging technology, and speculative and critical design elements.

My design process is a series of exercises in future casting, interesting design experiments with users, idea generation, what-if scenarios, and much making and testing with exciting technologies. For the most part, my outputs are objects that facilitate a digital-physical interaction, and at other times are illustrated prose narratives (sci-fi stories!), and videos. In the near future, I aim to keep generating interesting projects (client-led and self-initiated) in the same vein.

In your artistic statement, you say that in your work, you often try and look at humans as distinctly different from the nonhuman parts of our world but not above or dominant.

I would assert that humans are always dominant. Societies, politics, economies, wars, cultures and human aspirations are responsible for creating technologies, objects and services. Design, by definition, exists towards a purpose, a need, or an audience. If the research and development process were a double helix, I would see working with people as one strand and working with technology as the other one. The links between the two strands are user tests, research and experiments.

That said, we must consider the implications of the way we use our resources and capabilities as humankind to ensure a rational, judicial and sustainable approach in all phases of research, design and manufacturing.

Your graduation project AirWire is a new smart system that reads finger gestures and turns them to code to help make programming electronics as easy as swishing your fingers. Is it a speculative project? What is the intellectual process behind it?

Through my research, I came upon this conjecture: We often find the world of coding and electronics abstract and inaccessible. This problem isn’t one about logic. People understand the logical elements very well. The barrier to entry here is syntax and jargon – which is purely linguistic. Physical gestures, however, are very innate and intuitive. People have been using them in performance arts for centuries if not millennia. Can we use them in the code?

This is what led me to make AirWire. AirWire is a gesture-driven electronics prototyping platform. It allows users to perform intuitive gestures and interprets those as code to reduce the barrier to entry to coding for physical computing and electronics. It pulls the accurate and best practice code for every electronic component you’re using with the system.

Whilst I have a controlled working model that works with four different electronic components, I have also produced a “vision” video to explain the potential of gesture-controlled programming. Although its technology (gesture recognition and computer vision) is off the shelf, we may need a fleet of computer wizards and a few months to make it happen.

For my degree project design and development process, first, I made a bunch of blocks – each depicting an electronic component. I asked people from my user group to make an existing device and invent something new using those.

This helped me learn about modularity in making, and that even untrained people can guess the inner workings of devices. I then graduated to work in electronics and not just blocks. Then, I made and tested a bunch of demo rigs and dummy models to see how people interact with them and what technologies are really intuitive. Later, I finalised the technology for the model that would go in my Final show at the RCA and started developing it.

What is more important: to take yourself or not to take yourself too seriously to be creative?

The serious part of any project is working for a brief or towards a user. Though there can never be a set formula for creativity, I’ve always found that breaking down the project into fun mini-projects or exercises always makes the project lighter and generates a lot of great outputs.

Solitude or loneliness, how do you spend your time alone?

Recently, I’ve been saving the Hyrule Kingdom from the evil Calamity Ganon on Nintendo Switch. There is a stack of rejected ideas from my earlier brainstorming sessions that could easily spawn science fiction narratives, and I try to do that. I also enjoy sketching and doodling a lot!

One for the road… What are you unafraid of?

Stagnation.