Interview by Bilge Hasdemir

David Pescovitz is one of the creators of the vinyl reprint of the Voyager Golden Record. He is also a researcher director at the Institute for the Future, co-editor of the website Boing Boing and co-founder of Ozma Records. On top of that, he is a professional futurist. Working at the intersection of art, science and consciousness, Pescovitz likes the idea of telling stories and expanding the field of imagination by manipulating fictionalised realities and by provoking us to think about not only possible but also put-on future(s) as well.

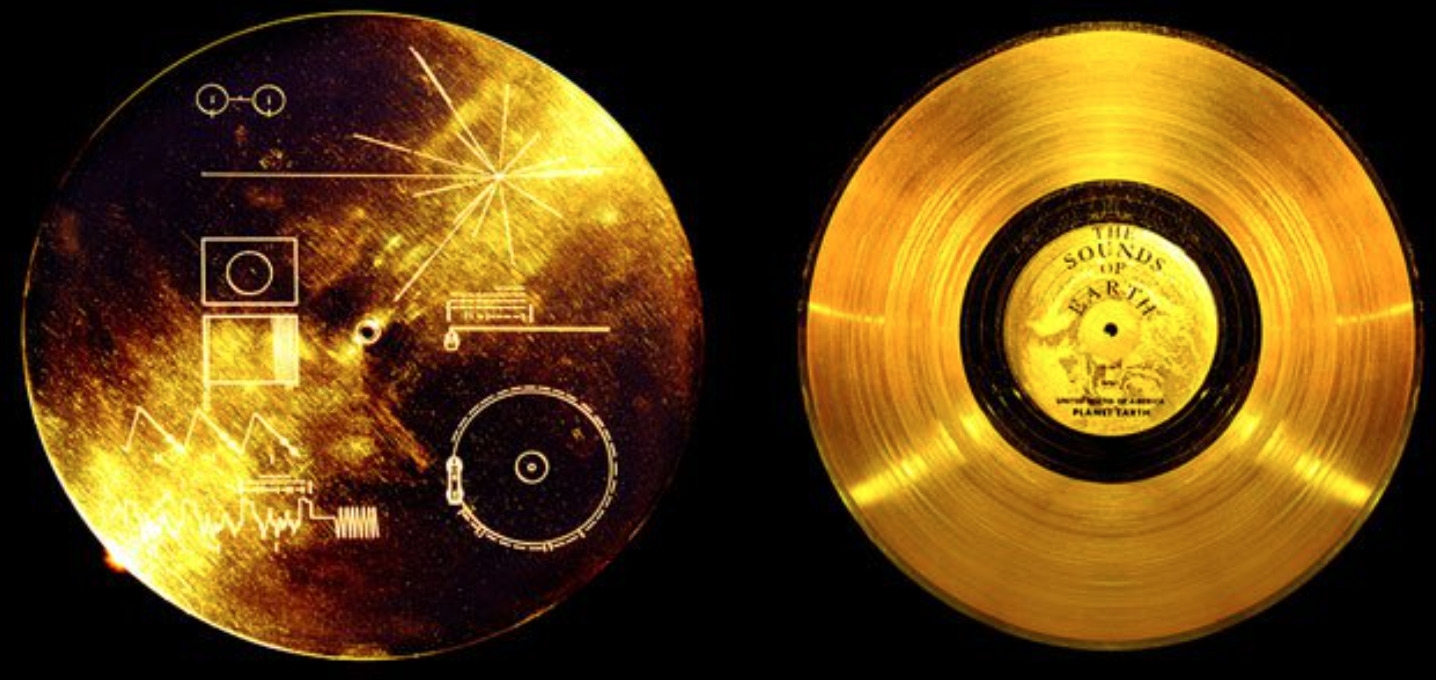

Together with Timothy Daly, and Lawrence Azerrad, they steer The Voyager Golden Records back to the Earth by reissuing the original record launched into space on the Voyager I and II spacecraft by NASA in 1977. The record, as an expression of the planet we are living on, includes a wide array of music, greetings spoken in 55 languages, various sounds from Earth, and photographs and diagrams depicting life on Earth and beyond as well. In line with this, it has to be emphasised that Carl Sagan and his associates, who selected the contents of the record for NASA, had truly a Gaian approach.

The record can be thought of as not only a message from Earth to extraterrestrials which can also be called as Earthly instructions for Cosmic use but a sacred archive of Planet Earth which includes a wide range of living beings’ repositories of its day. Starting as a Kickstarter project, there is no doubt that Golden Records has broken new ground.

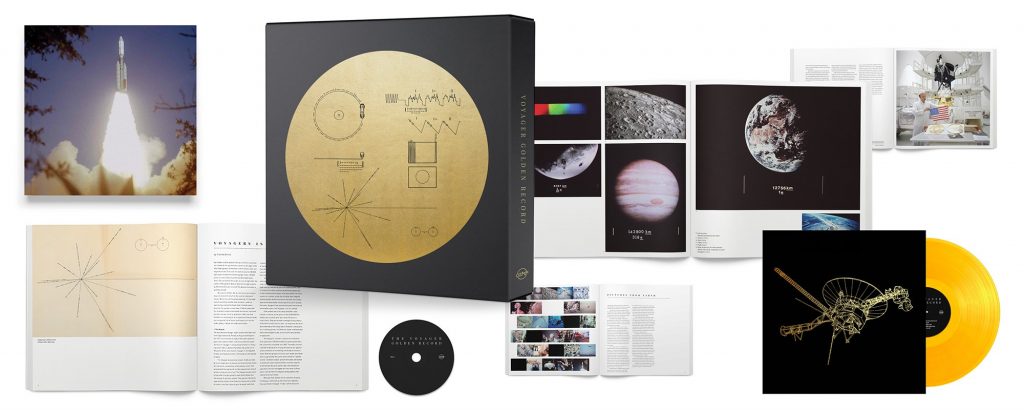

Ozma Records released the Golden Record on vinyl as the Voyager Golden Record: 40th Anniversary Edition. Nobody might assume that the support that they received at the very beginning of the project is a forerunner of the success and repercussions that will come. This year, it won a Grammy in the category Best Boxed or Special Limited Edition Package.

While the two copies are currently billions of miles away from Earth on the Voyager I and II spacecraft, 10.000 special edition copies of the records are now available on Earth. As we can all imagine that a large proportion of the original record sources are not available anymore. Therefore, on the one hand, the vinyl record is one which articulates the voice of the past as a vintage discovery. On the other hand, this auditory experience today allows listeners to confront the reality of an anthropogenically-effectuated mass extinction and loss as well.

Although today it might seem not possible to share the same optimism and hopefulness with the initiators of the Golden Record project while the absence of a future has already begun on this damaged Earth, the Voyager Golden Record might enable us to develop new visions to re-connect with the World and take an action to turn down our expanding trouble(s) slightly. It might be better to listen on the Voyager Golden Record as being aware of the fact that this is not music for relief, and there is a message from the extraterrestrial to humanity indeed.

What were the biggest challenges you faced in the development of the project? Was there any moment that you thought the project may not happen?

Tim, Lawrence and I are equal partners in this. Once we started, we felt no turning back. If we wouldn’t get the rights to some of the material, that would have made us less excited about doing it because we really wanted it to be complete.

But we’re really fortunate. We had tremendous support from the Major Record Labels, and then as I said, once I reached the people that needed to be contacted, once I found them and talked to them, the response was one of great support, and for that, we felt incredibly fortunate. But when we launched this as a Kickstarter, we did because we had no idea what the audience would be or what the size of the audience would be.

And in fact, one of the reasons that it was never put on record was because- and Sagan always wanted it to be on a record- was because the Record Labels couldn’t be judged if there was even a market for such a thing. And so, for us, we essentially used Kickstarter as a way to determine the size of that market by preorders, and we expected it to be, maybe, a couple of thousand people.

Then that initial Kickstarter was like 11,000 sets. It was just absolutely astounding. And it’s because the story of the record resonates with people, but once we started down the path, we never thought about what if this doesn’t happen? And we couldn’t think about that because before doing the Kickstarter, we had already spent a lot of our own personal money to pay for some of the rights. And imagine it didn’t happen. It wouldn’t have been good.

There were several challenging moments. We had some of the recordings and the indigenous people’s recordings, and we were trying to track down the information on them, and we would hit a dead end. For us, it was incredibly important that we respect the creators and contributors to the record and the artists and do this the right way.

And so, anytime we hit a closed door, there’s the question of, will we be able to clear the rights to this? Will we be able to find t the names of the people who performed or at least the people who recorded it? There were moments when we would get an email, and someone would say, oh, I think I found the recording. Is this the one that’s on the record? Does it match? And then you had to go and start all over again.

What’s one of the important messages of the Voyager Golden Record project?

What was particularly memorable or unique about this is that it isn’t just about sending information. It’s about the stars; it’s really a piece of conceptual art. I see it as a gift from humanity to the cosmos. There is no question that the people behind this project wanted to make this beautiful. These were people who had a deep appreciation for music and for art and for imagery, not people who were only concerned about presenting about sending information.

Do you have something planned for the record label after this release?

We don’t. We don’t have anything certain yet. We would like to do is do more projects, whether they’re musical or not, at the intersection of science and art and consciousness to spark the imagination and to tell stories. But what that’s going to be next we don’t know yet.

What do you think about the current renewed interest in space in culture and society in general?

A couple of things, I think there’s a renewed interest in space because of the privatisation and commercialisation of space. People are thinking about space more and more. Space has a long history of inspiring artists. For example, the new age music was very space-oriented, space rock. The idea of the mystery and the wonder and almost the unreachable that you can only get through science or through your imagination.

I think that’s a fertile place for artistic experimentation. And I also think that art and artists are often futurists; artists frequently raised questions about the future of science and technology that we haven’t been asking. In that way, they spark curiosity in conversation, and that’s essential. At the same time as art is a marvellous way to not just install a sense of curiosity but also present information.

But you also hear people saying why are we focused on space? We need to be protecting and saving our own planet. And I don’t think you have to choose one or the other. Their understanding of what lies beyond Earth can also inform the way we think about our own planet, even if you recall back, as much of the Voyager missions were about going beyond the outer planets.

Right before they turned off the cameras, in order to save energy for the scientific instrument, Carl Sagan convinced the team to turn it around and take one last picture, which was the Pale blue dot and that image, perhaps more than any other, has really lasted as an icon of thinking about how small we are in and how fragile our existences are.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Not giving myself time just to sit and think. Idleness fuels creativity.

You couldn’t live without…

My family, of course. And also music because it sparks the imagination and represents the diversity of the human experience.