Interview by Meritxell Rosell

When experiencing the installations of Nelo Akamatsu, one might be gently overcome by a delicate, physical sense of calmness. The artist incorporates Japanese culture, natural phenomena, and scientific knowledge into his pieces by utilising media such as electric devices, video and sound sculptures. Geomagnetism, glass, water and the sounds of their interactions are also central to Akamatsu’s most recent work, thus highlighting hidden patterns and rhythms that resonate within our daily lives.

Chozumakiis the result of Akamatsu’s Sonica (Glasgow) residence in 2017. The piece takes on one of the planet’s most mesmerising natural phenomena: the vortex. From atmospheric circulation to the spin of electrons to water swirling down plugholes, the geomagnetically-induced vortex has proven to be a hypnotising spectacle. Nelo Akamatsu’s Chozumaki will appeal to anyone who has worked in a biology or chemistry lab (who hasn’t spent hours trying to get the perfect solution). Glass beakers shaped like a cochlear duct, each one containing a continuous vortex produced by a magnetic stirrer, whirl endlessly in water; there’s a sort of mantric meditative repetition in sight and sound of these water vortex.

Chozumaki comes from chozubachi, a stone wash basin used to clean hands before a tea ceremony. In traditional Japanese culture, the water in the chozubachi purifies the body and mind before participation in the sacred tea ceremony itself. Water is associated with purification and meditative calmness in many cultures and is a central part of garden composition. For example, Persian and Islamic cultures designed magnificent gardens, such as the Alhambra in Granada, peaceful oases to hide away from the heat and noise with a pronounced sense of aesthetic composition and where water was a central element. Similarly, in Japanese culture, as Akamatsu says: the concepts of traditional Japanese gardens are based on the perspective of fluctuation in nature, and my sense of fluctuation resonates with the rhythm and the vibration of the air and water in Japanese gardens.

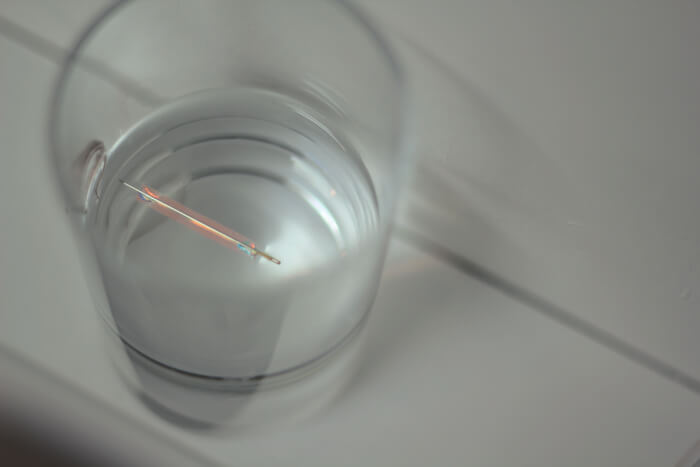

Suikinkutsu accounts for a sound installation for the traditional Japanese garden, invented in the Edo period. The sounds of water drops falling into an earthenware pot buried under a stone wash basin resonate through hollow bamboo utensils. And as we can see, water plays a very prominent role in Akamatsu’s art. In Chijikinkutsu, another of Akamastsu’s pieces, he uses the principle of geomagnetism1 – chijiki – to explore the traditional form of sound sculpture – suikinkutsu. The piece – awarded a Golden Nica at Ars Electronica 2015- shows electro-magnetised needles gently striking the walls of water-filled glass vessels. The needles produce a delicate rhythmic clink as they respond to the influence of the geomagnetic forces, confronting the observer with the hidden strength of these movements and, after a while, transporting them in a meditative state.

On many occasions, we have documented Japanese people’s particular sensibility towards nature and aesthetics; since ancient times, Japanese people have been sensitive to perceiving nature as it is, from the sound of the wind through pine trees or the singing of insects in each season. However, Akamatsu also shares with us that his pieces shouldn’t be overthought: sometimes there is no need to find any narrative, just finding the perfect aesthetic balance between the materials and elements of the piece, in perfect syntony, just like a Japanese garden.

1 The Earth’s magnetic field (or geomagnetic field) is a phenomenon that influences human activity and the natural world in a myriad of ways. The geomagnetic field changes from place to place and on time scales ranging from seconds to decades to eons. These changes can affect health and safety and economic well-being. Since long before the Age of Discovery, people have travelled with navigation using compasses employing geomagnetism. In recent years, various devices that utilise geomagnetism have even been incorporated into smartphones. However, its s cause of generation is not yet entirely unearthed by modern physics.

You are a multidisciplinary artist, working across several media, such as sound and video installations, sculptures, paintings and photography. Your work also takes inspiration from nature and natural phenomena. How and when did this interest come about?

My experiences and feelings have accumulated for many years like a lump of lint. The lint of my sense of curiosity into natural phenomena [has also been woven into it, present] since my childhood. When one thread is, by chance, unravelled from the lump, a new artwork comes into being. It could happen by a mere sight just passing [by] me or [by] an instant flashback to my dream after awakening.

If you create an artwork based on a specific theme, the creative process usually begins with [the verbalisation of a narrative]. [Contrastingly], my type of creation–by unravelling a thread–always gives birth to abstraction without any narratives at the beginning, but [instead] with materialisation, symbolisation and vibration.

Chijikinkutsu is a minimalistic sound installation that uses geomagnetism. Could you tell us about the intellectual process behind the piece?

The reason why CHIJIKINKUTSU and CHOZUMAKI seem so minimal is [because] I’m presenting materials such as water, glass tumblers, sewing needles, etc., and [phenomena such] as geomagnetism and vortexes, and sounds such as glasses [clinking] and [the movement of] water, just [the way they are all found in nature]. I don’t follow the surrealistic approach, like the [presentation of] impossibles, nor the cinematic method of montages; I didn’t express any narratives there.

Chozumaki is another one of your installations inspired by the relationship between typhoon swirls and the Coriolis force: An intricate installation of glass and water uses magnetic energy to produce a spiralling vortex of curious sounds. What were some of the biggest challenges in this piece’s development?

I utilise magnetic energy as [both] a pigment and canvas for my artistic expression. For CHOZUMAKI, I created special devices [to showcase] vortexes as [naturally as possible]. I also [made various] adjustments to the level of magnetic power, the shape and size of the rotor, the speed of rotation, and the quantity of water in the vessels, all making for unstable, [differential] fluctuations in the vortexes, [all to reference how water found] in the seas, rivers, and waterfalls changes its shape, colour, and sound in every minute of the day, and every season of the year.

It’s similar [to how] Japanese gardens don’t look artificial because the gardeners take great pains to express nature [realistically]. Though it sounds contradictory, expressing nature for me is, in a sense creating a sustainable state of instability.

How does working with natural phenomena affect your perception of the impact of human existence on the planet?

Humans can never control the devastating power of earthquakes and hurricanes. But even if the power of the earth is that enormous, humans have given an incredible level of damage to the planet with global warming by discharging CO2, destruction of the ecosystem, radioactive pollution and so on. However, I’m somewhat optimistic that humans could live their ecological lives if artificial intelligence disempowers human thoughts shortly.

Japan has an ancient tradition of garden sound design using natural elements, and many Western musicians, artists, and writers have been fascinated by it. For example, John Cage composed Ryoanji, a musical translation of the famous Karesansui garden in Kyoto. Which elements of garden spacial sound design are the most inspiring for your work? Unlike traditional European gardens, which value the concept of symmetry, you can rarely see symmetric landscapes in traditional Japanese gardens. Karesansui at Ryoanji is one of the best gardens showing asymmetry’s beauty.

Though you might think there’re symmetric objects in nature, like snow crystals and foliage, they are not exactly symmetric because of their knobs and mutations that you can find if you observe very closely. So we, humans, live in nature with its fluctuation, which always overcomes mathematical regularity. I think traditional Japanese gardens are based on this perspective of natural fluctuation. And my sense of fluctuation resonant with the rhythm and the vibration of the air and water in Japanese gardens.

What is your chief enemy of creativity?

Hesitations sometimes make it difficult to be as I am. The enemies of my creation don’t always emerge from the outside but come from the inside of myself; when I try to solve the problems caused by such internal enemies, I can propel my creativity simultaneously. So I shouldn’t simply eliminate them.

You couldn’t live without…

All the possible desires, of course, include the passion for creation.